Solar Wind Source Found

Astronomershave finally tracked down the missing starting point of one of the two types ofsolar wind.

The solarwind is a stream of electrically charged particles that flows constantly outfrom the sun in all directions. The particles can make the journey from the sunto the Earth in fewer than 10 days and, when the wind turns into a storm,create the magnificent auroras that dance across polar skies when they interactwith the Earth's magnetic field.

The partsof the solar wind that emanate from the sun's equatorial region originate atthe edges of bright regions in the sun's atmosphere and are released when the magneticfields of two bright regions link up, scientists announced last week at theRoyal Astronomical Society's National Astronomy Meeting in Belfast, NorthernIreland.

"It isfantastic to finally be able to pinpoint the source of the solar wind ? it hasbeen debated for many years and now we have the final piece of thejigsaw," said study leader Louise Harra of University College London.

Fast andslow

The sunemits radiation, which is pure energy, along with the solar wind, which isfast-moving matter. The wind's particles are accelerated by the sun's magneticfields, and the configuration of the magnetic fields can influence how fast thesolar wind is going when it rushes out into space.

Astronomersrecognize two types of solar wind, distinguished by their speed. The fast one isknown to originate from coronal hole regions near the sun's poles and travel atabout 1.8 million miles per hour (2.9 million kilometers per hour). The slow oneflows from the equatorial region of the sun at about 432,000 mph to 1.1 millionmph (720,000 kph to 1.8 million kph).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The fast solarwind is so much faster because the magnetic fields that loop out from the polarregions are always "open," meaning they don't loop back toward thesun's surface. So "all the gas can keep streaming out, there's nothing tostop it," Harra said.

At theequator, on the other hand, there are both closed and open magnetic fields, andthe closed fields hold the solarplasma back. Only when the fields open, can the solar wind stream out fromthe region.

As aresult, the solar wind coming from the equatorial region is slower and"very, very variable," Harra told SPACE.com.

Big and'baby' regions

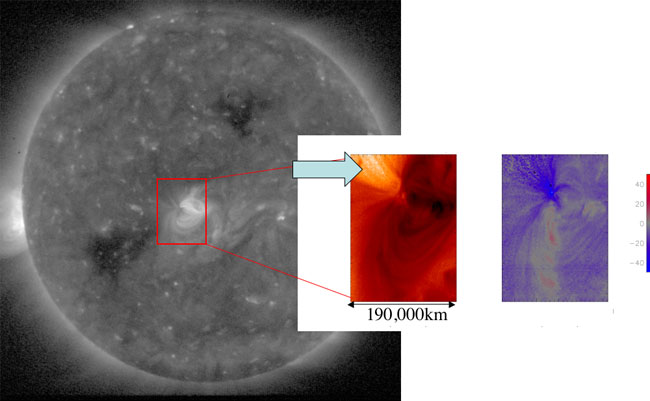

Using the Hinodespace observatory, Harra and her colleagues found for the first time that hotgas spurts out at high speeds from the edges of bright, active regions alongthe equator when the magnetic fields from two regions meet up.

Hinodewitnessed such a link-up when the field lines from a big active region and a"baby" region connected and opened up.

"Wenow know that interacting with smaller regions can open up the fieldlines," Harra said.

Theseregions can connect even when they are 500,000 kilometers apart (a distanceequivalent to placing 40 Earths side-by-side), Harra said.

For the tworegions to connect, the field lines from the two regions have to be in theright direction and of the right strength.

The bigregion "needs to find its partner to interact," Harra said.

Understandingthe solar wind and how it is formed could help scientists better predict how itwill affect the Earth and help protect the satellites in orbit around ourplanet.

- Video: Danger! Solar Storm

- Double Vision: STEREO Spacecraft to Scan Sun in 3D

- Images: Sun Storms

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.