Giant Mystery Blob Discovered Near Dawn of Time

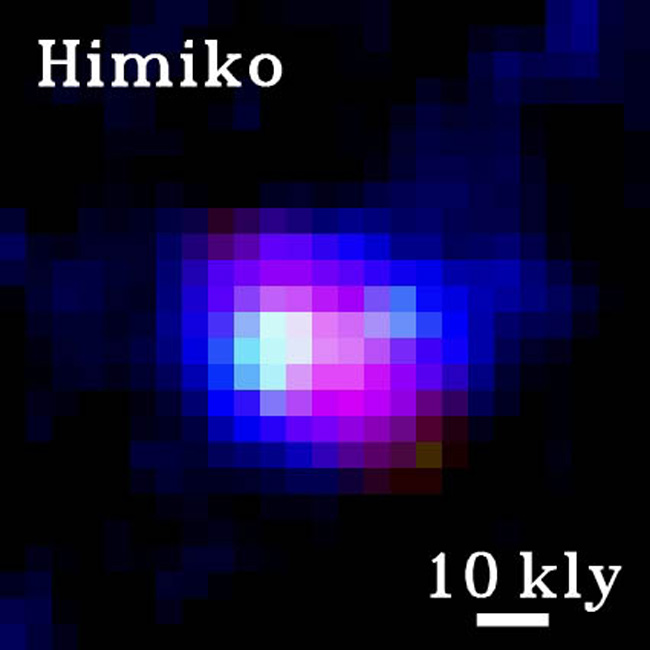

A newly found primordial blob may represent the mostmassive object ever discovered in the early universe, researchers announcedtoday.

The gas cloud, spotted from 12.9 billion light-years away,could signal the earliest stages of galaxy formation back when the universe wasjust 800 million years old.

"I have never heard about any [similar] objects thatcould be resolved at this distance," said Masami Ouchi, a researcherat the Carnegie Institution in Pasadena, Calif. "It's kindof record-breaking."

A light-year is the distance light travels in a year,about 6 trillion miles (10 trillion kilometers). An object 12.9 billionlight-years away is seen asit existed 12.9 billion years ago, and the light is just now arriving.

The cloud predates similar blobs, known as Lyman-Alphablobs, which existed when the universe was 2 billion to 3 billion years old.Researchers named their new find Himiko, after an ancient Japanese queen withan equally murky past.

Himiko holds more than 10 times as much mass as the nextlargest object found in the early universe, or roughly the equivalent mass of40 billion suns. At 55,000 light years across, it spans about half the diameterof our Milky Way Galaxy.

Lyman-Alpha blobs remain a mystery because existingtelescopes have a hard time peering so far back to nearly the dawn of theuniverse.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Himiko sits right on the doorstep of an era called the reionizationepoch, which lasted between 200 million and 1 billion years after the BigBang. That's when the universe had just emerged from its cosmic dark ages andhad begun brightening through the formation of stars and galaxies. Hot,energized hydrogen gas from that time period has allowed astronomers to beginseeing some objects — as much good as it does to squint at such fuzzy blobs.

"Even for astronomers, we don't understand,"Ouchi told SPACE.com. "We are keen to try to understand what thosesystems are in the reionization epoch."

Himiko may represent an ionized gas halo surrounding a super-massiveblack hole, or a cooling gas cloud that indicates a primordial galaxy,Ouchi noted. But it might also be the result of a collision between two younggalaxies, or the outgoing wind of a highly active star nursery, or a singlegiant galaxy.

Pinning down this riddle will require further telescopetime. The W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii can help accurately estimate starformation in the blob, while NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory could test thesuper-massive black hole scenario, Ouchi noted. And even Hubble could get in onthe action.

"We're planning deep infrared imaging with theHubble Space Telescope to tell whether [Himiko] has merger-like qualities ornot," Ouchi said.

However, that particular research hinges upon the futuresuccess of a riskyrepair mission to the aging Hubble. Astronauts are slated to blast off withthe space shuttle Atlantis in the attempt next month.

For now, researchers may celebrate the fact that theyfound Himiko at all. They almost overlooked the blob among 207 galaxycandidates, while sweeping a portion of the sky designated theSubaru/XMM-Newton Deep Survey Field.

After making the initial sighting with the Subarutelescope in Hawaii in 2007, Ouchi and his colleagues followed up usinginstruments from the Keck/DEIMOS and Magellan/IMACS arrays. Thosespectrographic observations allowed them to pinpoint the signature of theionized hydrogen gas and determine the distance and age of the mysteriousHimiko.

"We never believed that this bright and large sourcewas a real distant object," Ouchi said. "We thought it was aforeground interloper contaminating our galaxy sample. But we triedanyway."

- Images: Hubble's New Views of the Universe

- Video - Galaxy Collisions

- Vote - The Strangest Things in Space

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.