Famous Crab Nebula Shoots Off Mysterious Flares

One of the most well-known celestial objects still has some tricks up its sleeve, according to a new discovery of surprising gamma-ray flares coming from the famous Crab Nebula.

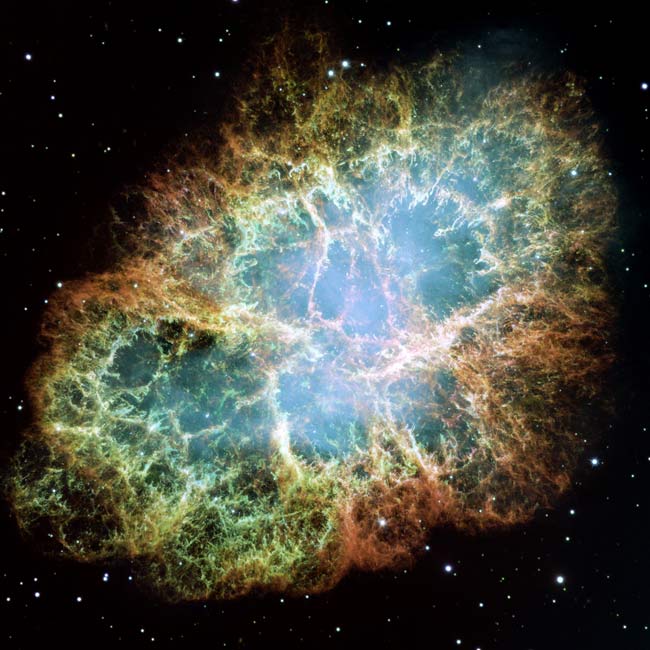

The Crab, long-considered such a steady celestial light that it was used to calibrate other sources, has now had three flare-ups where it brightened significantly in the gamma-ray range for a few days, astronomers report. [Hubble photo of the Crab nebula]

"Our belief of a stable Crab got smashed completely — now we have to think again," said Marco Tavani, an astronomer at the INAF-IASF (Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica-Istituto di Astrofisica Spaziale e Fisica Cosmica) in Rome. Tavani was lead author of one of two papers announcing the discovery of the flares in the Jan. 7 issue of the journal Science.

Tavani's team used the Italian Space Agency's AGILE satellite to observe flares in October 2007 and September 2010. Another team, led by Stefan Funk and Rolf Buehler at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory at Stanford University, observed the September 2010 flare as well, along with one in February 2009, using NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope.

"We had always thought we understand essentially what is going on in the Crab Nebula, but obviously these flares we didn't expect," Funk told SPACE.com.

The Crab Nebula is actually the burial ground of a long-dead star. Its photogenic layers of colorful gas are the sloughed-off remains of the star's body, ejected before it collapsed in on itself to create a dense hulk called a neutron star.

The particular neutron star at the heart of the Crab Nebula is called a pulsar, because it emits a continuous beam of radiation like a lighthouse that appears to pulse when it crosses Earth's line of sight.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Yet why this nebula is emitting these strange flares is not known. These flares, which each lasted a few days, are different from gamma-ray bursts, which are much shorter explosions of light sometimes created when a massive star dies.

"It's still a real mystery what is the ultimate cause," Tavani said.

The basic idea is that the pulsar releases a stream of charged particles that get accelerated — though by what means remains open to debate. When the particles — mostly electrons and their positively charged siblings, positrons — hit the nebula surrounding the pulsar, they interact with the nebula's magnetic field, causing them to release a type of light known as synchrotron radiation, which is mostly in the form of gamma rays.

These are the first such gamma-ray flares to be seen from any nebula.

"It's essentially telling us something new about how particles are accelerated in astrophysical objects, in particular in these nebulae," Funk said.

This acceleration is about 1,000 times more energetic than the largest man-made particle accelerators, including Fermilab's Tevatron in Illinois and CERN's Large Hadron Collider in Geneva, Tavani said.

The cosmic particle accelerator in the Crab is speeding up those electrons and positrons to nearly the speed of light. As a result, the gamma rays they release are of higher energies than any others ever before seen from astrophysical sources.

"The ultimate goal of the studies is to really understand the process of particle acceleration," Tavani said. "This would be really great for models and theories that can address how particles are accelerated to these very large energies."

There are still many unanswered questions about the mechanism at work in the Crab Nebula, including why it flares up only periodically.

"It's very exciting and it's very important to continue to study it," Tavani said.

The researchers hope to catch the Crab Nebula in the act of flaring up in the future, as well as to possibly observe the phenomenon in other nebulas.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.