New Radar Could Reveal Secrets of Earth's Ice Sheets

Thisstory was updated on May 7, 2008.

Aspace-based radar aboard a European Mars probe could help peer beneath thesurface of Earth's ice sheets, not to mention the frozen extraterrestrial seasof moons like Europa and Titan.

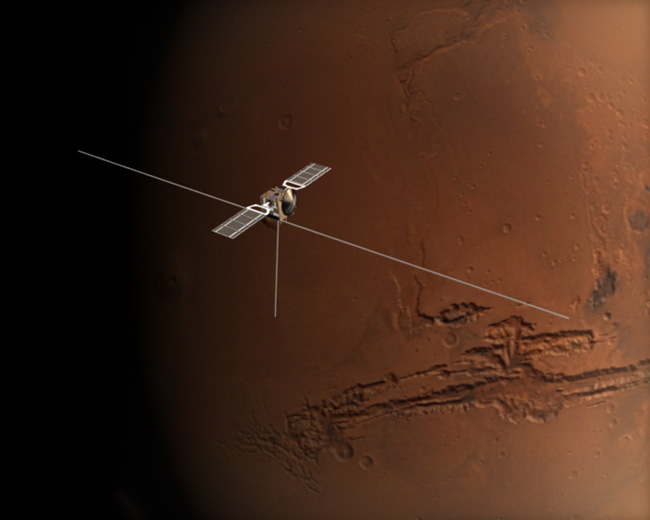

The spaceradar would take its cue from the Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface andIonosphere Sounding (MARSIS) instrument, which has probed the RedPlanet's underground for evidence of water from the European Space Agency?s(ESA) MarsExpress spacecraft.

"I washaving discussions with scientists from MARSIS, and I saw that what they haddone could be applicable to Earth," said Florence Heliere, the ESA technicalmanager heading the concept study.

MarsExpress wields a 131-foot (40-meter) long MARSISantenna boom that dwarfs the spacecraft's six-foot wide span, like a giantwhiplash antenna on a tiny car. That main antenna pings the Martian surfacewith radar to try and detect underground water, but also receives a lot ofunwanted clutter signals from the Martian surface and surrounding undergroundlayers.

A second,smaller antenna detects only the scattered clutter signals that do not comefrom the target area directly below Mars Express. Scientists couldtheoretically subtract the clutter signals from the main antenna signal to getthe true target reading, but the Mars Express team ultimately drew up adifferent solution that did not require the second antenna.

Still, the Mars dryrun has inspired the early development of the Advanced Concept for RadarSounder (ACRAS) that will set its initial sights on Earth?s Antarctic icesheets.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Antarcticais an area where the ice is cold and dry, so you can penetrate up to 3-4kilometers (1.8-2.5 miles) within the ice," Heliere told SPACE.com.

Continuousobservation by ACRAS would help estimate the thickness of the Antarctic andother polar locations, as well as determine the three-dimensional internalstructure of the ice sheets. Climate modelers could use data from the tool toget a better idea of how the ice sheets change over time as ice melts andreforms.

But theACRAS team faces several hurdles in adapting space-based radar technologydeveloped for Mars into an Earth-observing tool.

First, theMars Express radar works between 1.3 and 5 MHz on the electromagnetic spectrum,but international regulations only give bandwidth around 435 MHz for Earthobservation. Scientists typically observe the Earth with airborne or otherradar systems that use around 60 MHz or 150 MHz, but Heliere hopes to test the435 MHz system through airborne trial runs starting next week.

Anotherchallenge has been wrestling with the clutter signals from a target?s regionalsurroundings. ACRAS will use a solution similar to MARSIS to screen outunwanted clutter from the cross-track direction, or at right angles to thedirection of travel of its parent spacecraft. Although MARSIS used a secondaryantenna to pick up clutter signals, ACRAS will use just one antenna that cansend out and receive several different radar signals, Heliere noted.

A differentsolution will screen out clutter coming from the direction of the spacecraft'sline of travel, taking advantage of the Doppler Effect where returning signalsmeet the spacecraft flying head-on in their direction and appear to condense.The same effect causes the drop in an ambulance siren's wail as the vehiclespeeds past, and would allow scientists to pick out the clutter in the signals.

The thirdchallenge involves addressing distortion of the radar signal from the upperpart of the Earth's atmosphere, called the ionosphere. The German Space Agency(DLR) has developed an autofocus technique that supposedly deals withionosphere distortion, and will publish results of their test simulations inthe near future, according to Heliere.

ACRAS couldsee action by 2015 onboard ESA's Biomass Explorer mission, assuming thatsatellite gets the green light, Heliere said. More distant possibilitiesinclude deploying the radar to Jupiter'smoon Europa or Saturn'smoon Titan, with each suspected of harboringoceans beneath their frozen crusts.

"This [couldbe] applicable to Titan, Europa or Mars again to improve the capabilities ofradar sounding," Heliere said. "I originally worked on Earth as themain subject, so [looking at MARSIS] has opened doors to other things."

- NEW VIDEO: Europe Explores Mars

- IMAGES: Ancient Mars ? A Waterworld Imagined

- VIDEO: Parachuting Onto Titan

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.