Why There's No Replacement for the Space Shuttle

NASA's space shuttles are retiring this year, but America has no spaceship to replace them, leaving many to wonder: Why not?

After the wheels of the space shuttle roll to a stop for the final time, NASA astronauts will have to rely on Russian spaceships for their rides into space until commercial American vehicles are ready to fly crews to orbit. A capsule-based spacecraft, called Orion, is also in development, but NASA's current plans are to use it primarily as an escape ship for the International Space Station.

So why hasn't NASA already built a "Space Shuttle 2" – a more economical, more technologically up-to-date reusable space plane?

Over the course of the shuttle program's 30-year career, NASA and its various partners explored a number of different vehicle options to succeed the space shuttles, but none were brought to fruition, said Roger Launius, space history curator at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum, in Washington.

"The landscape is littered with failed shuttle follow-on programs," Launius told SPACE.com.

One by one, each program ended after development plans bumped up against funding and politics – an experience familiar throughout NASA's history.

"There's a whole series of factors – some of them were political, but a lot of the problems were technical," Launius said. "Could they have been solved if they had more money? Probably. So, was it a technical problem or a political problem? I could argue both sides." [Total Space Shuttle Program Cost: Nearly $200 Billion]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Pushing further out into the solar system

NASA is retiring its three remaining space shuttles to focus on future missions to an asteroid and eventually Mars. Meanwhile, the private sector has been charged with developing spacecraft to reach the International Space Station and other possible destinations in low-Earth orbit. [NASA's Space Shuttle: Top to Bottom]

Until then, there will be a gap in American spaceflight similar to the years between the end of the Apollo moon program and the inception of the space shuttles, said NASA's deputy chief Lori Garver.

"NASA has relived this history quite a bit since Apollo," Garver told SPACE.com. "When we talk to our colleagues who are running space agencies around the world, we all struggle with, ‘How do you ramp up a new program while still operating the old one?’ And none of us have really found a way to do that without these gaps."

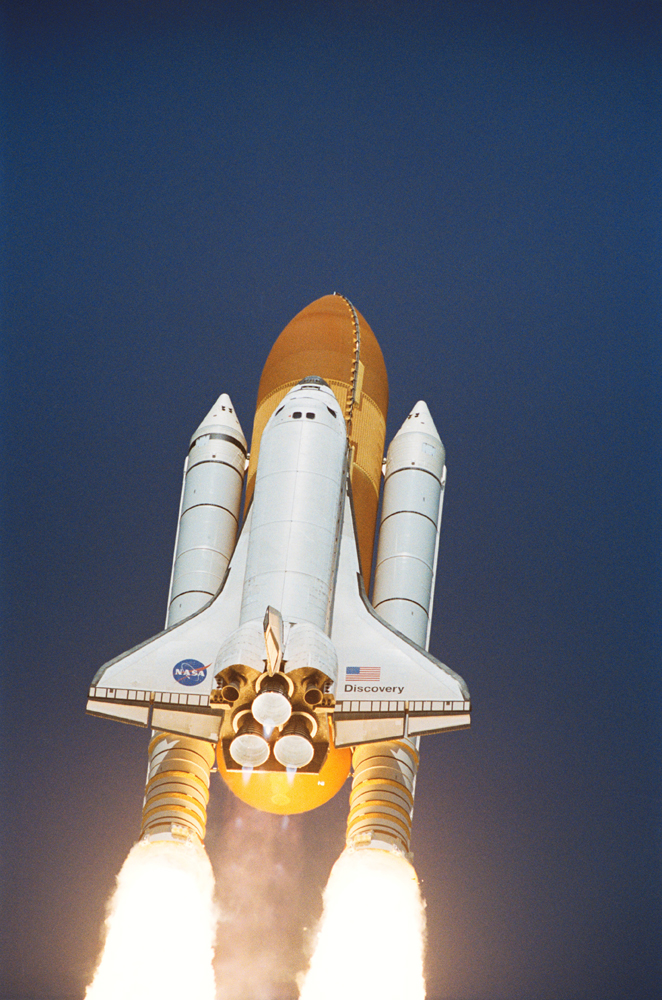

Discovery, Endeavour and Atlantis could continue to fly beyond 2011 given the appropriate funds, but some experts agree that the vehicles' retirement is necessary to pave the way for the construction of more-sophisticated spacecraft, including ones to explore farther out into the solar system.

"You could continue to fly the shuttle – in theory, it can be done," Launius said. "But is that the right thing to do, or has that train left the station? I think a lot of people would say it has probably left."

For Wayne Hale, NASA's former space shuttle program manager, ending the shuttle program is the crucial next step to ensure that America's spaceflight program is constantly evolving.

"There are other considerations beyond the money," Hale told SPACE.com. "Technology has advanced, and we need to build a new, safer, more economical next generation. Think what would happen if the Wright brothers said, 'Okay, the thing we built in 1903, it flew. We don't need to make any improvements, we'll just sell those.' The way you advance is by making improvements and building new vehicles and getting something more capable." [Q&A with Former Shuttle Chief Wayne Hale]

Searching for a replacement

Still, the various failed programs to succeed the space shuttles are examples of how difficult that can be. One example is the National Aerospace Plane, Launius said.

In the 1980s, NASA and the Air Force collaborated on a highly secretive project known as the X-30 National Aerospace Plane (NASP). Due to the classified nature of the project, few details are known, but the concept was envisioned as a single-stage-to-orbit space plane. The program lasted over a decade, but technical hurdles and budgetary issues forced its eventual cancellation in 1993, before a prototype could be built.

Other test programs that fell short include the X-33, which was a joint development between NASA and Lockheed Martin in the mid-1990s. The X-33 suborbital space plane was planned as a technology demonstrator for Lockheed's proposed VentureStar orbital spacecraft.

"This was another space plane concept, a potential shuttle follow-on, in which NASA and Lockheed both put money," Launius said. "But it was underfunded and there wasn't the political support for it. They again ran into technical problems, and no one was willing to open a pocketbook to solve those, and that program was canceled as well."

Among other test programs, NASA experimented with a cargo-only version of the space shuttle, called Shuttle-C. This side-mounted carrier would be flown from the ground, unmanned, and used solely to ferry supplies into low-Earth orbit.

"I went to work for NASA in 1990, and when I arrived there, this was one of the big things they were working on," Launius said. "It was essentially a modification to the shuttle, but it never got the approval necessary to move beyond the study phase."

More than just a political fight

There were reasons besides political and technical challenges that these test programs did not get much further than the design stage, Hale said. Ironically, one of them may have been the shuttles' reputation as workhorses, with their strong records of achievement.

"My take on the reason we don't have a second shuttle is that the shuttle we have did its job too well," Hale said. "It was just good enough – it wasn't as economical as we wanted, and as we found out, not as safe as we wanted, but it was effective enough to never cross the threshold to the point where we said we needed to replace them."

According to Hale, NASA should have been developing a second-generation space shuttle in the 1980s, long before the disastrous loss of the shuttle Columbia and President George W. Bush's unveiling in 2004 of a new vision that laid the foundation for the shuttles' retirement.

However, "the policymakers just never saw the need, because the shuttle was doing everything just good enough that we could continue to get by," Hale said.

You can follow SPACE.com staff writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.