Clearing the Air: Smaller Detectors Needed for Moon, Mars Missions

No matter what mission astronautswill carry out on the moon and Mars during future planetary expeditions, theywill certainly have to breathe.

To make sure their air is clean, ateam of NASA researchers and Spacehab engineers haveteamed up to develop miniaturized detectors which, they hope, will lead to acompact, real-time air monitoring system for future spacecraft.

"It will be increasingly importantas we get past the space station on to the moon or Mars," said John James,NASA's chief toxicologist at Johnson Space Center, in a telephone interview."Right now, we don't have space shuttles going back and forth to the station,so it is difficult to get air samples back down for analysis."

NASA's space shuttle fleet has beengrounded since the Columbia disaster in 2003, in which the Columbia orbiter andits seven-astronaut crew were lost during reentry. The space agency is planningto launch its first return to flight mission, STS-114 aboard the shuttleDiscovery, no early than July 13. In the meantime, Russian Soyuz spacecrafthave returned archival air samples to scientists on Earth.

But it is a new space-based systemthat James and Spacehab hope to develop.

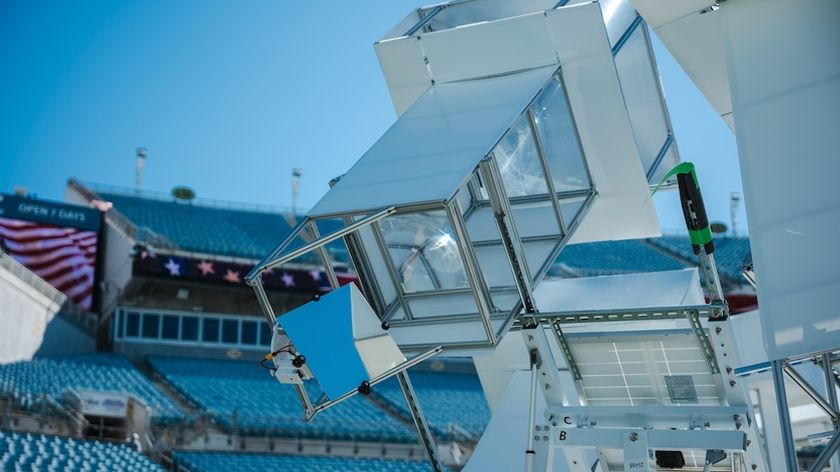

Under a two-year partnership betweenNASA and Spacehab, researchers will test miniaturemass spectrometers, instruments that detect and measure the amount ofpollutants in a given environment, in order to develop better spacecraft lifesupport systems.

"Air pollutants can affectyour health, and some people are more susceptible than others," James said,adding that the effects of contaminated air can also vary. "Sometimes they'renon-specific, and only cause reports of headache or mild, flu-like symptoms."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Spacecraft air is recycledrepeatedly, which could lead to an accumulation of harmful compounds, researcherssaid. The possibility of leaking equipment, such as the chemical halon from onboard fire extinguishers, is also cause forconcern, they added.

Bringing down the weight

Most mass spectrometers on themarket today weigh about 100 pounds (45 kilograms) and can be as large as a cartrunk, much too big and heavy for spaceflight, NASA officials said. The massspectrometer inside the nitrogen-oxygen air quality system aboard theInternational Space Station (ISS) is about the size of a large suitcase, butJames hopes future versions can be even smaller still.

A separateinstrument, the volatile organic analyzer (VOA) uses a method called gaschromatograph ion mobility spectrometry to track the slow build-up of tracecontaminants onboard the ISS on a monthly basis. That instrument, a 96-pound(43-kilogram) tool about the size of a mid-deck locker, failed in July 2003.

"Thattechnology is not going to get us to the moon," said Nigel Packham,manager of NASA's environmental factors office for the station at JSC. "It istoo big, and it is too heavy."

Spacehab officials are calling upon thenanotechnology-expertise of the Richardson, Texas-based company Zyvex to scale down mass spectrometer size.

"These little things [would] have anadvantage in that you could deploy three, four or five of them around as a kindof first-alert system," James said. "I see that as very valuable for a lunar orMars [human] habitat."

A real-time system would also be vitalsince lunar and Mars astronauts would be too far from home to send an airsample back to Earth for analysis, NASA officials said.

Packham said ISS astronauts currently use devices called grab sample containers and dualabsorbent tubes to collect station air samples and send them back home to Earth.The most recent batch of samples arrived home with the crew of ISS Expedition10, whose Russian Soyuz spacecraft landedin Kazakhstan on April 24.

"We have nocurrent real-time monitoring system in place," he said, adding there are alsoother projects underway to minimize instrument weight. "For example, [the JetPropulsion Laboratory] is working on a miniature gas chromatograph mass spectrometer."

A captive environment

Space-bound astronauts, such as thesix-month crews assigned to the ISS, can be more sensitive to air pollutantsbecause of their contained environment.

"It's magnified in the sense thatyour exposure is continuous," James said. "Workers with industrial exposures onEarth are exposed between six and eight hours a day, but in space habitat youcan't just go home."

In February 2002, ISS Expedition 4astronauts had to confine themselves temporarily to the Russian segment of thespace station after detecting a foul odorin the U.S.-built Quest airlock. The offending, but non-toxic, smell originatedin a recyclable metal oxide (Metox) canister used toclean and recharge air scrubbers for U.S. space suits, NASA officials said.

"We call it the 'MetoxIncident,'" James said. "Basically, we went to desorbsome filters used in the air scrubbers and they released some noxiouscompounds."

A fireaboard the Russian space station Mir in 1997 also gave NASA researchers samplesof contaminated air, which were collected by astronaut Jerry Linenger after a faulty oxygen-generating canister sentflames and smoke billowing through the orbital outpost. Linengerand the rest of Mir's crew also contended with rising carbon-dioxide levels andleaking antifreeze fumes.

James said that one of the majorhurdles facing mass spectrometer miniaturization is how small engineers canpush the device without losing performance. Retaining reliability too, will bea focus.

"Honestly, I think the technology isto the point that there's some good opportunity for spin-off on Earth," hesaid, adding that simple carbon monoxide monitoring in homes is just one ofmany potential uses. "There are Homeland Security opportunities and perhaps somespecials applications where you might want to monitor high risk areas."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.