Orbital Overload: Space Debris Crowds the Not-So-Friendly Skies

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

As dump-sites go, there's nothing quite like Earth orbit: Totally gone or near-dead spacecraft, spent motor casings and rocket stages, all the way down to pieces of solid propellant, insulation, and paint flakes. Toss in for good measure thousands of frozen bits of still-radioactive nuclear reactor coolant dribbling from a number of aged Russian radar satellites.

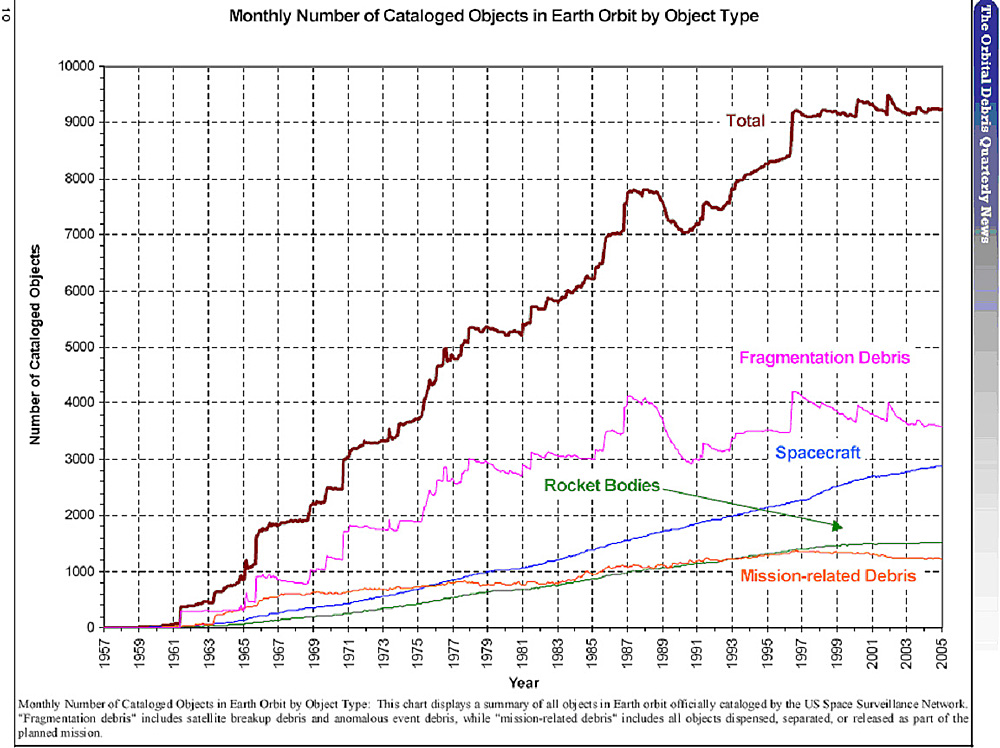

Here's the heavenly clutter count as of December 29, 2004.

There were 9,233 objects large enough to be tracked and catalogued by the USSTRATCOM Space Surveillance Network. Of this total there were 2,927 payloads, along with 6,306 object classed as rocket bodies and debris.

That's the stats as listed in the January issue of The Orbital Debris Quarterly News, issued by the NASA Johnson Space Center Orbital Debris Program Office in Houston, Texas.

Hardware survivors

A major contributor to orbital debris is an object suddenly breaking up. This can be caused when propellant and oxidizer inadvertently mix; leftover fuel becomes overpressurized due to heating; or when onboard batteries blow their tops. Some spacecraft have been purposely detonated. Explosions can also be indirectly triggered by collisions with fast-moving debris.

An example of fragmentation took place last October. A Russian Proton Block DM auxiliary motor busted up, adding more than 60 pieces of junk to the overall orbital debris scene.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

At times some of this high-tech scrap survives its fiery plunge through Earth's atmosphere. A growing list of these hardware survivors is maintained by The Center for Orbital and Reentry Debris Studies at The Aerospace Corporation in El Segundo, California.

Last year, for instance, a titanium rocket-motor casing weighing roughly 155 pounds (70 kilograms) was found near San Roque in Argentina. It was identified as debris from a third stage of an American Delta 2 booster that had been orbiting since October 1993.

Similarly, in July a metal pressure sphere and metal fragment fell into Brazil, the likely debris from a second stage of a Delta 2 booster that hurled the Mars Exploration Rover, Opportunity, toward the red planet a year earlier.

Solar max and minimum

So what's the overall report card on orbiting trash look like over the years?

Fragmentation debris appears to have decreased noticeably in recent years, but unfortunately the true picture is slightly different, said Nicholas Johnson, Program Manager and Chief Scientist of the NASA Orbital Debris Program Office at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

"A significant number of fragmentation debris objects have been created during the period and are being tracked by the Space Surveillance Network, but they have not yet been officially cataloged," Johnson told SPACE.com. "This is a bureaucratic issue rather than an environmental one. Meanwhile, spacecraft and rocket bodies continue to accumulate, although for the latter the rate of increase is now small."

There's another "message" that can be seen in charting out the space junk saga, found in the relative numbers of spacecraft, rocket bodies, and other debris.

Johnson said that that we are nearing solar minimum when reentries -- particularly for small debris -- normally taper off. There was a clear decrease in the population around 1990 during a period of high solar activity. "Unfortunately, the last solar max did not produce a similar result," he said.

Fall of Hubble

So far this month there have been a couple of U.S. Delta rocket stages that have reentered, as well as a Russian Proton motor.

All this is small stuff compared to something big coming in on its own -- like the Hubble Space Telescope. There's good reason why an eventual "controlled" reentry is being planned for that orbiting eye on the universe.

Orbital debris analysts have figured out the risk to humans down below if Hubble should plow through the Earth's atmosphere in an uncontrolled manner.

At least two tons (2,055 kilograms) of the estimated 26,000 pounds (11,792 kilograms) of the observatory would survive the plummet from space. Such a fall would produce a debris track that stretches over 755 miles (1,220 kilometers) in length. The analysis suggests that the risk posed to the human population in the year 2020 is 1:250 -- a risk that exceeds NASA's own safety standard.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.