The monster black hole at the Milky Way's heart isn't the only celestial beast capable of booting stars out of the galaxy, a new study suggests.

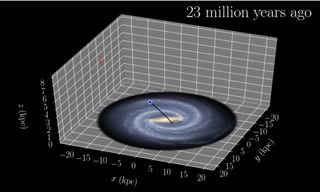

Astronomers traced the trajectory of a huge "hypervelocity star" backward through time. They found that the star, known as LAMOST-HVS1, got its speed kick in the Milky Way's disk, not near the galactic core where the supermassive black hole lurks, as had previously been suspected, a new study reports.

"This discovery dramatically changes our view on the origin of fast-moving stars," study co-author Monica Valluri, an astronomy professor at the University of Michigan, said in a statement.

Related: Black Holes of the Universe in Images

"The fact that the trajectory of this massive, fast-moving star originates in the disk rather that at the galactic center indicates that the very extreme environments needed to eject fast-moving stars can arise in places other than around supermassive black holes," Valluri added.

Hypervelocity stars zoom through space at speeds exceeding 1 million mph (1.6 million km/h) — more than twice as fast as their "normal" cousins. These speedsters are pretty rare; astronomers first spotted one in 2005 and have cataloged fewer than 30 since then.

To reach their tremendous speeds, hypervelocity stars must experience a powerful gravitational slingshot. The chief suspect in most cases is Sagittarius A*, the Milky Way's central black hole, which harbors about 4 million times the mass of Earth's sun.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But something else appears to be going on with LAMOST-HVS1, which is Earth's closest known hypervelocity star. The exotic object lies about 42,000 light-years from us. For perspective, the Milky Way's spiral disk is about 100,000 light-years wide.

Valluri and her colleagues, led by University of Michigan postdoctoral researcher Kohei Hattori, traced LAMOST-HVS1's path using observations made by Europe's Gaia spacecraft and one of the twin Magellan telescopes, which are part of Las Campanas Observatory in Chile.

"We thought this star came from the galactic center. But if you look at its trajectory, it is clear that is not related to the galactic center," Hattori said in the same statement. "We have to consider other possibilities for the origin of the star."

Hattori and his colleagues don't know how LAMOST-HVS1 got its speed boost, but they point out two main possibilities: The star may have had gravitational encounters with multiple massive stars, or it may have been slung out of the disk by an intermediate-mass black hole within a star cluster.

LAMOST-HVS1's apparent path originates at a spot within a Milky Way spiral arm known as Norma. No star clusters are known to exist in that location, the researchers said, but one could lurk there, hidden by dust.

So, LAMOST-HVS1's slingshot locale may be a good place to hunt for intermediate-mass black holes. These mysterious objects — whose masses fall between those of stellar-mass black holes and those of supermassive black holes — are thought to be common throughout the Milky Way. but they have proved very difficult to find or study.

The new study was published online Tuesday (March 12) in The Astrophysical Journal.

- Stunning Photos of Our Milky Way Galaxy

- Milky Way Quiz: Test Your Galaxy Smarts

- Our Milky Way Galaxy: A Traveler's Guide (Infographic)

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.