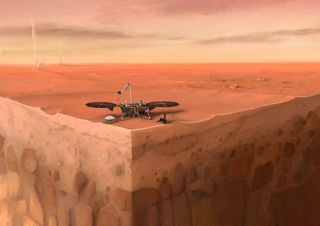

The 'mole' on Mars will dig no more, NASA says

The heat-seeking probe won't reach its target depth.

A Martian "mole" will stop its valiant attempts to dig on the Red Planet.

After it landed in 2018, NASA's InSight spacecraft's heat probe, or "mole," dealt with friction problems as investigators worked to try and learn more about the internal heat sources powering Mars. When the mole burrowed in, however, it would bounce back off of the unexpectedly hard regolith (or soil).

NASA announced Thursday (Jan. 14) that the German Aerospace Center (DLR)-built mole would abandon its historic mission to deploy the first underground mole on Mars.

The decision was announced days after an external scientific review board — considering a routine NASA request to extend InSight's mission based on its scientific output — publicly approved the mission extension, but requested the agency pursue the mole's work at a lower priority. The review board's report also noted that InSight is likely to run out of power before its newly extended mission ends in December 2022, unless certain instruments are deprioritized.

Mars InSight in photos: NASA's mission to probe core of the Red Planet

InSight's last attempt to drive the mole underground took place Jan. 9. With assistance from ground controllers on Earth, the mole moved about an inch (2 or 3 cm) under the surface, and the team used a scoop on the spacecraft's robotic arm "to scrape soil onto the probe and tamp it down to provide added friction," NASA said in the same announcement.

Controllers instructed InSight to make 500 hammer strokes to drive the mole in, but the probe didn't budge from its shallow perch. The mission originally called for InSight to deploy sensors once the mole was 10 feet (3 meters) under the surface, but the mole never made it further than a few inches.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We've given it everything we've got, but Mars and our heroic mole remain incompatible," DLR's Tilman Spohn, principal investigator of the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package instrument that includes the mole, said in the NASA statement. "Fortunately, we've learned a lot that will benefit future missions that attempt to dig into the subsurface," he added.

"What we attempted to do — to dig so deep with a device so small — is unprecedented," Troy Hudson, a scientist and engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory who led the mole's efforts, said in the same NASA statement. "Having had the opportunity to take this [effort] all the way to the end is the greatest reward."

Future Mars missions will want to move underground for applications such as accessing water ice, or for hunting for microbial life under the surface, NASA noted. Why InSight failed to dig into the Martian surface came down to "unexpected properties" of the soil, the agency said, which proved harder to push through than the material that two previous Mars missions encountered.

While the mole failed to reach its primary objective, the team behind the probe learned other lessons from the experience. The team had InSight using its arm and scoop in ways that engineers never anticipated, such as using those tools to push against and down on the mole.

This hard-earned experience will come in handy when InSight's robotic arm buries the tether that sends data and power to the craft's seismometer. Once the tether is under the Martian regolith, it will be better protected from temperature changes that affect the quality of seismic data. Still, despite such challenges, InSight has recorded more than 480 Marsquakes after about two Earth years on the Red Planet, NASA said.

InSight's extended mission will not only include quake monitoring, the craft will also collect data via a radio experiment to learn whether the planet's core is solid or liquid. Weather sensors will also help scientists to better understand meteorological conditions on Mars, along with data from NASA's ongoing Curiosity rover mission (which deployed weather instruments in 2012) and the NASA Perseverance rover, set to land on Mars Feb. 18.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace