A Mars Rover’s Great Escape

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

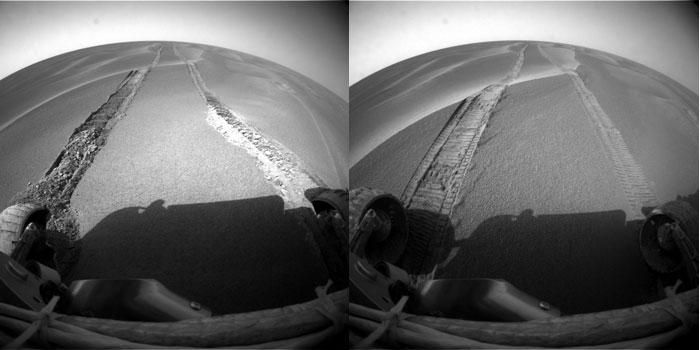

The Opportunity Mars rover is on the move again, but it took nearly five weeks of frustrating work for controllers back on Earth to make it happen.

And now, great care is being taken not to have a repeat performance of the six-wheeled robot getting bogged down in martian sand dunes within its zone of exploration at Meridiani Planum. Before a new traverse gets underway, Mars teams are piecing together as top priority a strategy to avoid similar dunes in the future.

"When we hit the dune, we were doing what we call a 'blind drive'", said Steve Squyres of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York and the principal investigator for the science instruments aboard both Opportunity and Spirit rovers.

Squyres said a blind drive is one in which ground controllers are not checking the rate of the rover's forward progress. Not even looking for obstacles.

"The good thing about blind driving is that it's fast...we can cover a lot of ground that way. But we can only use it in terrain that we think is very benign," Squyres told SPACE.com. "Because we had safely driven over so many other dunes in the past, blind driving seemed appropriate in this terrain."

But that decision proved wrong. The rover had a run in with soft sand of a small martian dune.

"There was something different about this dune that got us," Squyres explained. That sand trap proved to be "a real learning experience!"

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cautious and deliberate driving

There are a number of lessons learned, spurring a bit of rewriting in the operator's manual for Opportunity as it cruises the open parking lot-like landscape of Meridiani Planum.

"We definitely will not be doing long blind drives in this terrain for awhile. Instead, we'll start turning back on many of the safety checks that we have in our driving software, proceeding much more cautiously," Squyres said. "We'll also try to plan our drives so that we stay in the troughs between the dunes, rather than driving up and over them."

These changes will slow Opportunity's driving down.

It is doubtful, for instance, that the robot will be doing any more of those over 650-feet (200-meter) treks across Mars anytime soon, Squyres suggested. "But we feel pretty confident that we can continue to make good progress using this more cautious and deliberate driving strategy," he added.

Taking the "Erebus Highway"

What's the next move for Opportunity?

Squyres said that will depend on how much time the rover team spends on studying the dune the robot got stuck in. "We're still working out exactly what we're going to do, so I'm not prepared right now to guess how long it'll take."

But once that's done, the plan is for the robot to start moving again, and toward the south.

"We're still very interested in getting to Erebus crater," Squyres said. The Mars machine is about 1,312 feet (400 meters) from that crater. But it is less than 395 feet (120-meters) from what's dubbed the "Erebus Highway".

"This is a feature we've seen from orbit that looks like a strip of bright material leading toward the crater. Our guess all along has been that the bright material in the etched terrain is largely exposed bedrock," Squyres said. If that guess is right, he continued, then the Erebus Highway is indeed a thoroughfare that may offer relatively safe and easy driving.

"We don't know for sure that it's rock, though. If it is something else -- like dust -- then

it could be a trap instead of a highway. There's no way to be sure from the orbital images," Squyres said.

So the plan - akin to what the rover teams have done in the past -- is simply to go there and find out.

"If the highway offers safe driving, then it's southward ho and on to Erebus. If it doesn't, then we'll stop and think," Squyres concluded.

Layered deposits

As Opportunity unstuck itself, on the other side of Mars the Spirit rover has been busily working at Gusev Crater.

Now over a year-and-a-half after its landing in 2004, Spirit is rolling through a range of hills labeled the "Columbia Hills."

Spirit wrapped up observations last week on Larry's Outcrop, part of a series of outcrops -- Methuselah, Jibsheet, Larry's Lookout -- on the north flank of Husband Hill in the Columbia Hills.

"Part of the work load has been understanding the chemistry and mineralogy of these outcrops," said Larry Crumpler, a research curator in volcanology and space sciences at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science in Albuquerque. He is on the Mars rover science team.

"The outcrops consist of layered deposits, possibly volcanic and certainly altered. But, because these layers are tilted, the other part of the work has been trying to get well-determined estimates of the orientation. These are what geologists refer to as 'strike and dip'...that is, the azimuth of the outcrop layers and the tilt of the layers," Crumpler told SPACE.com.

Field geology on Mars

There are several outcrops, Crumpler said, and it is difficult to draw a line between the layers in one outcrop, particularly Jibsheet, and connect it with the layers just examined on Larry's Outcrop.

Mars scientists want to determine if the variations being seen are just lateral variations in alteration of the same layer or whether they are looking at bedding lying at different levels - which started out with different chemistry and mineralogy.

"By knowing the exact orientation we can make projections from one outcrop to the other," Crumpler said. Geologists do this all the time in the field on Earth using a compass and inclinometer...reconstructing stratigraphy [the origin, composition, distribution and succession of strata in layered rocks or sediments] from several unconnected outcrops, he noted.

"Doing that on Earth is hard enough, but we are doing it very remotely on the surface of another planet. We really are doing field geology on Mars," Crumpler said.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.