There is Added Urgency to Shuttle Fuel Tank Repairs

NEW ORLEANS -- The detective work is ending. Now it's time for the men toting spray guns to get to work.

In a hulking factory on the outskirts of New Orleans, they're finally starting to rebuild the fuel tank that will fly with Discovery on the first shuttle mission since a chunk of orange foam from another tank made here led to the destruction of Columbia and killed seven astronauts.

Only this time, after building and flying more than 100 of the behemoth tanks, everyone working on this tank knows the leeway for mistakes is far smaller than anyone imagined. Nineteen months of tests show a piece of the lightweight foam as small as a hamburger bun can bring down one of the mighty space shuttles.

"This is not easy," said Neil Otte, the tank's chief engineer, during a media tour Thursday of the Michoud Assembly Facility, where the tanks are made.

NASA and Lockheed Martin Space Systems Co. admit they will never completely eliminate the decades-old problem of foam popping off the tank during shuttle launches. They're convinced, however, that they've figured out how to dramatically reduce the size and amount of the foam chunks that batter the orbiters' brittle heat shields.

"This tank is going to be much safer," said Sandy Coleman, the manager of NASA's external tank project office at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama. "We want more than anything to protect our astronauts. They're part of our family."

She is not alone delivering that message. In the hallway just outside the doors the tank-builders must pass through is a poster of the next shuttle commander, Eileen Collins, holding her daughter. The poster's sobering slogan: "Are you ready for us to go? Think safety."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Making the tank much safer, NASA found, goes far beyond the decision to lop off the suitcase-sized foam triangles called "bipod ramps." It was one of those foam ramps that popped free during Columbia's flight, punching a hole the size of a car tire in the orbiter's left wing. As Columbia plunged back through the atmosphere on Feb. 1, 2003, the superhot gases that envelop the orbiter got inside the wing and ripped the spaceship apart.

So the ramps on External Tank No. 120 are gone. Instead of the foam, a heated copper plate will keep ice from building up on the V-shaped metal struts that hook the tank to the orbiter. A slight change in the metal will keep the material from overheating on the way to space.

NASA decided on that change a few months after the accident, but engineers and managers gave the final go-ahead for workers to retrofit Discovery's tank a month ago.

That's just the most visible change. Several others were prompted by newfound knowledge that foam far smaller than the 2-pound piece that hit Columbia could be deadly.

To hold it in your hand, the foam weighs less than a Styrofoam beer cooler. Hence, NASA's long-held assumption that the stuff could do nothing more than gouge pits in the heat-shielding tiles that were a headache to repair but not a danger to the ship or its crews.

Columbia exposed that as folly. Reaching more than twice the speed of sound in the first couple of minutes after blasting off from Kennedy Space Center, the shuttle is moving so fast that blocks of foam the size of a coffee cup could hit with enough force to open a deadly gash in the orbiter's protective armor.

Another dangerous assumption: NASA assumed the foam was applied perfectly, every time. After the accident, investigators sliced and diced other tanks being built here and found air pockets, cracks and other flaws that could cause foam to pop loose.

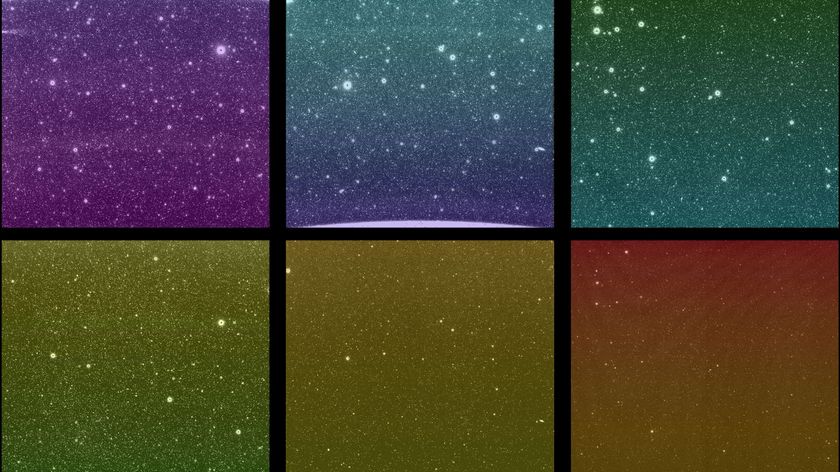

Robots spray a near-perfect layer of foam across about 95 percent of the tank. In hard to reach places with bumps, grooves or other odd surfaces, men spray or pour the foam into place. That's where most flaws hide.

"That wasn't the fault of the guys putting it on," Otte said. "They were doing the job that we gave them and it was just a tough job."

Instead, Otte and his team found, the application process itself contributed to the defects. NASA and contractor teams wrote procedures decades ago as they designed the shuttle, but apparently never checked to see whether it worked. What came out of the factory never matched the design.

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board chided NASA for not doing more study about how the foam fails. The post-accident studies drove the changes.

A thick ridge of foam covering a seam where the hydrogen tank is bolted to the cone-shaped oxygen tank is being reworked. Nitrogen inside the tank has been creeping through tiny gaps in bolt threads, into air pockets in the foam, later expanding to pop foot-wide divots. Now workers are spraying there more carefully, eliminating hidden voids. They're also injecting insulation into the tiniest of crevices.

An exposed spot along a fuel pipe outside the tank is being retooled so water will drip away instead of forming a thick, potentially deadly ice ring. Another ramp-like section of foam will be sprayed more carefully to avoid any chance it might pop loose.

Some ideas came from tank workers. Others designed by engineers were perfected in countless practice sessions by men who've been coating the tanks with foam for 20 years.

"You've got to let them practice," Otte said. "You've got to give them the right process that they can do over and over again." The sprayers now get to "try different things until they find something that works that they can do consistently."

Michoud is due to ship the tank, via ocean barge, to Kennedy Space Center by October or November to meet a spring launch date.

"Quality of that tank is first and foremost," said Hal Simoneaux, the Lockheed Martin manager heading the tank retrofit. "If we have to take a schedule hit to get it right, we will."

Published under license from FLORIDA TODAY. Copyright ? 2004 FLORIDA TODAY. No portion of this material may be reproduced in any way without the written consent of FLORIDA TODAY.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

John Kelly is the director of data journalism for ABC-owned TV stations at Walt Disney Television. An investigative reporter and data journalist, John covered space exploration, NASA and aerospace as a reporter for Florida Today for 11 years, four of those on the Space Reporter beat. John earned a journalism degree from the University of Kentucky and wrote for the Shelbyville News and Associated Press before joining Florida Today's space team. In 2013, John joined the data investigation team at USA Today and became director of data journalism there in 2018 before joining Disney in 2019. John is a two-time winner of the Edward R. Murrow award in 2020 and 2021, won a Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting in 2020 and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Investigative Reporting in 2017. You can follow John on Twitter.