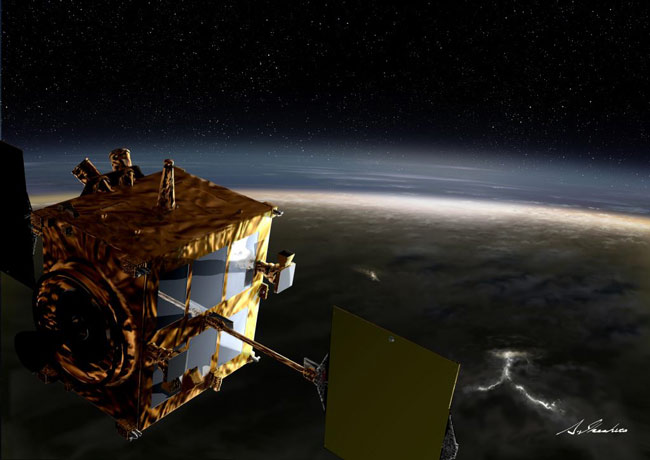

After more than six months of interplanetary travel, a space probe from Japan arrived at Venus yesterday, but the fate of its mission to study the hellishly hot planet's extreme weather is uncertain, according to the Japanese space agency and press reports.

The $300 million Akatsuki spacecraft, whose name means "Dawn" in Japanese, arrived at Venus Monday (Dec. 6) at 6:49 p.m. EST (2349 GMT), when it was expected to fire its thrusters to enter orbit around the cloud-covered planet. It was early Tuesday morning Japan Standard Time at the probe's mission control center in Japan during the maneuver.

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency overseeing the mission confirmed ignition of Akatsuki's thrusters for its planned maneuver to enter orbit just before the probe swung behind Venus for an expected 22-minute break in communications.

But the communications blackout lasted an unexpectedly long 1 1/2 hours, according to Japan's Mainichi Daily News newspaper. The press service Agence-France Presse reported that JAXA officials suspected that the Venus probe was not in the proper orbit and not using all of its communications antennas after contact resumed.

"It is not known which path the probe is following at the moment," the AFP quoted JAXA official Munetaka Ueno as saying Tuesday. "We are making maximum effort to readjust the probe."

Venus up close

JAXA has high hopes for Akatsuki to help astronomers better understand Venus.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Akatsuki launched from Japan's Tanegashima Space Center on May 20 with the solar-sail spacecraft Ikaros and is designed to spend at least the next two years studying Venus' clouds, atmosphere and weather in unprecedented detail.

One main goal is to see how Venus veered off on such an extreme path, becoming an inhospitable world with thick sulfuric-acid clouds and surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead, JAXA officials have said. [Gallery: Beneath the Clouds of Venus]

"In so many ways, Venus is similar to Earth. It has about the same mass, is approximately the same distance from the sun and is made of the same basic materials," Akatsuki project scientist Takeshi Imamura said in a statement. "Yet the two worlds ended up so different. We want to know why."

The Akatsuki spacecraft has five different cameras to monitor the Venusian atmosphere in a variety of wavelengths, from infrared to visible to ultraviolet light.

The spacecraft will circle the planet's equator in a highly elliptical orbit that brings it as close as 186 miles (300 kilometers) and reaches as far out as 49,709 miles (80,000 km). Akatsuki's orbit will allow the probe to scrutinize parts of Venus' atmosphere for 20 hours at a time, JAXA officials have said.

Such a long look will enable researchers to see how Venus' cloud patterns change over time.

"We'll assemble the images to produce a cloud motion time-lapse movie, much like a weather forecaster on television might show you of Earth," Imamura said.

Hellish planet's atmosphere

Akatsuki will also search for clues as to how Venus' sulfuric-acid clouds — which form a layer 12 miles (20 km) thick — originate and evolve, officials have said. The spacecraft's infrared instruments, for example, will scan the planet's surface for volcanic activity, which could spew sulfur into the Venusian air.

Many scientists think that Venus has volcanoes, but the planet's thick clouds have so far frustrated attempts to confirm this.

Another Venus orbiter, the European Space Agency's Venus Express spacecraft, detected lightning crackling through the planet's hot air in 2005. This surprised scientists who had assumed that lightning could form only in atmospheres with lots of water-ice crystals, which build up electrical charges via collisions.

So Akatsuki will try to figure out how Venus lightning flares up — if there is indeed another way to generate this fire in the sky.

Venus Express is still studying the planet from its polar orbit, and the arrival of Akatsuki, with its complementary orbit and abilities, should help astronomers better understand the weather on Earth's hellish twin, researchers have said.

"Using Akatsuki to investigate the atmosphere of Venus and comparing it with that of Earth, we hope to learn more about the factors determining planetary environments," Imamura said in a video posted to JAXA's website.

JAXA officials said they plan to issue new updates on the state of Akatsuki as events unfold.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.