SpaceX Launches DSCOVR Space Weather Satellite, But No Rocket Landing

The third time was the charm for SpaceX Wednesday (Feb. 11) with the launch of a long-delayed space weather satellite on a million-mile trek into deep space.

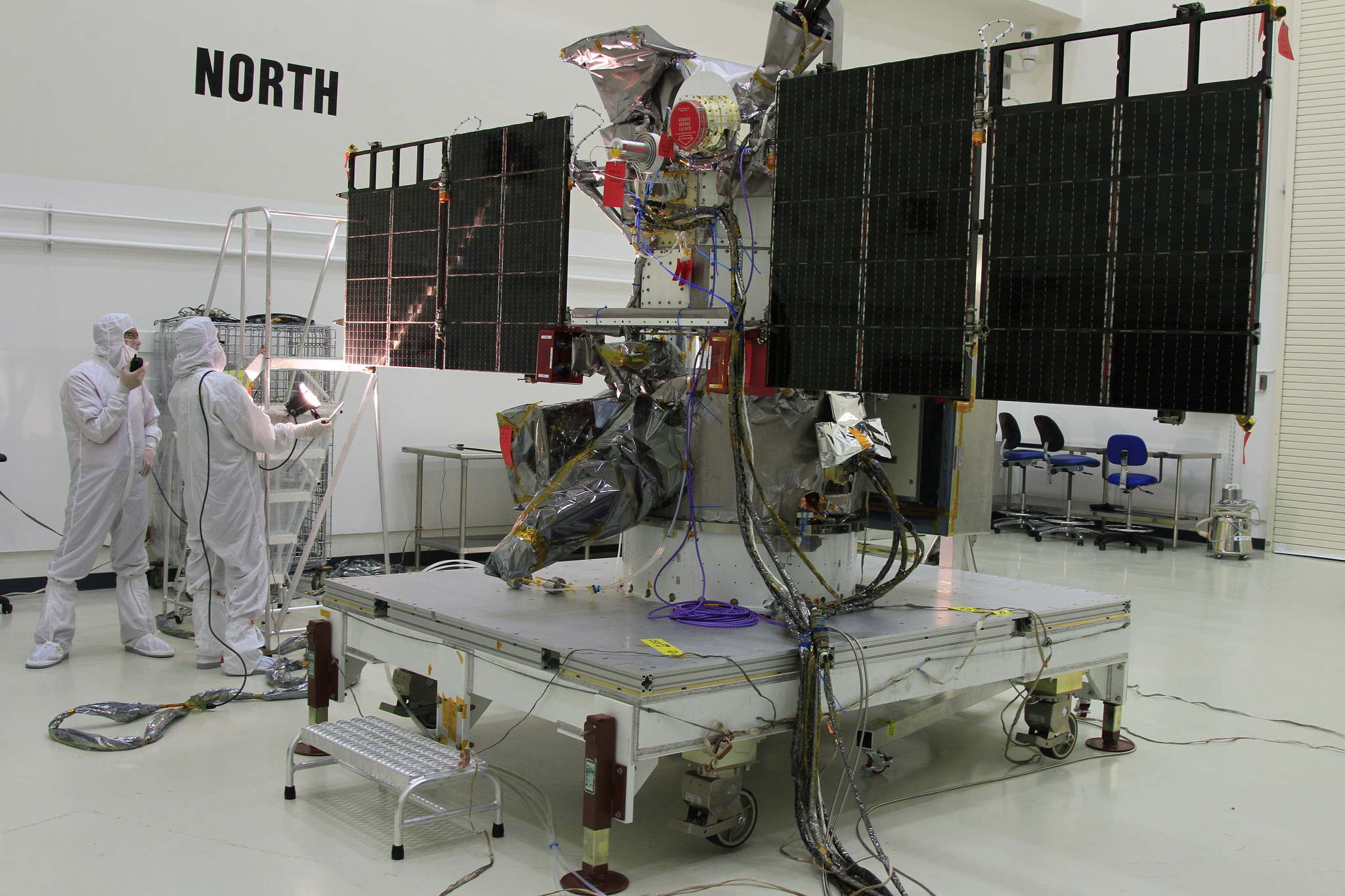

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket launched into orbit at 6:03 p.m. EST (2303 GMT) carrying the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR), a satellite designed to serve as an early-warning system for potentially dangerous solar storms. SpaceX was initially schedule to deliver the satellite on Sunday, but a series of delays pushed the launch to today. Video of the SpaceX launch showed the rocket soaring serenely into the sunset sky above its Cape Canaveral Air Force Station launch site in Florida.

After delivering the satellite to space, the Falcon 9 rocket's first stage was initially expected to re-enter Earth's atmosphere for a landing attempt on a SpaceX drone ship parked in the Atlantic. Representatives with the spaceflight company, however, decided not to attempt the drone ship landing due to bad weather in the ocean at the landing site. [See the DSCOVR mission in photos]

"The Falcon takes flight! Propelling the Deep Space Climate Observatory on a million-mile journey to protect our planet Earth," explained NASA spokesman Mike Curie during launch commentary. "A beautiful ascent."

SpaceX did manage to bring the rocket stage back for a soft ocean landing Wednesday, as it has done during previous Falcon 9 launches, company founder and CEO Elon Musk said.

"Rocket soft landed in the ocean within 10m of target & nicely vertical! High probability of good droneship landing in non-stormy weather," Musk said via Twitter Wednesday.

The company attempted to land a Falcon 9 rocket first stage on the ship last month, but the booster ran out of hydraulic fluid for its four grid steering fins. It ultimately reached the drone ship, but landed hard, crashing and exploding in a brilliant fireball.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Musk christened the drone ship originally scheduled to be used for this landing try "Just Read the Instructions" after the sentient colony ship of the same name in the novels of science fiction author Iain M. Banks.

DSCOVR finally reaches space

The DSCOVR satellite is a partnership of NASA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Air Force and has been in the works for more than 10 years. The satellite was originally approved in 1998 under the name Triana as a NASA Earth science mission championed by then-Vice President Al Gore for its mission to beam live views of the sunlit of Earth for science and educational purposes.

"The constant ability to see the earth whole, fully sunlit every single day; the opportunity for every man, woman and child who lives on the Earth to see, if they wish, their own home in the context of the whole, can add to our way of thinking about our relationship to the Earth," Gore said during a press event taped by Space.com partner Spaceflight Now in Florida before launch.

But cost overruns and political debates (the satellite was sometimes called "GoreSat" by critics) led to the Triana project's cancellation in 2001. The completed satellite was placed in storage until 2009, when NOAA and NASA resurrected the spacecraft as a space weather sentry.

"It was inspiring to witness the launch of the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR)," Gore wrote in a statement posted on his blog just after liftoff. "DSCOVR has embarked on its mission to further our understanding of Earth and enable citizens and scientists alike to better understand the reality of the climate crisis and envision its solutions. DSCOVR will also give us a wonderful opportunity to see the beauty and fragility of our planet and, in doing so, remind us of the duty to protect our only home."

Now, the $340 million DSCOVR should help create an early-alert system for space weather, letting NOAA scientists know when harmful space weather could put satellites in orbit or power grids on Earth in danger. The spacecraft is now heading to its far-off orbit, a point 1 million miles (1.6 million km) from Earth known as Lagrange 1 to begin its solar sentry mission. [The Biggest Solar Storms of 2014]

A space weather tsunami buoy

The sun can erupt with large coronal mass ejections — explosions of super-hot plasma that shoot out from the star during solar storms or flares. When aimed directly at Earth, charged particles from these eruptions could harm satellites and astronauts in space as well as systems on the planet. Solar wind can actually knock power grids offline and disrupt telecommunications and GPS when it forcefully impacts Earth's magnetic field, according to NASA.

"Occasionally the sun will have a large eruption of magnetic field and energetic particles and if that comes toward the Earth and collides with the Earth's magnetic field in the magnetosphere, that's when you could get disturbances that we call solar or geomagnetic storms," Tom Berger, director of NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Office, said in a video on the DSCOVR mission. "These geomagnetic storms can be very damaging to critical infrastructure on Earth such as power grids, aviation communication systems, satellites in orbit."

Scientists hope that once DSCOVR reaches its L1 destination, the mission will be able to let officials on the ground know 15 to 60 minutes before a geomagnetic storm strikes. It will also serve as a backup for NASA's aging Advanced Composition Explorer, which has been monitoring the sun's solar weather activity since 1997 and is far beyond its original operational life.

Berger said ACE was originally built as a research satellite, not as an operational space weather buoy in deep space. That is why DSCOVR is so vital, he added.

"We're really looking forward to having a true space weather satellite monitoring the sun from L1," Berger said just before launch.

Solar storms that could disrupt the power grid are relatively few and far between. One of the biggest space weather-related events, dubbed the Carrington Event, happened in 1859. The huge storm lit telegraph lines on fire, and if a storm of that level occurred again without warning, it could upset computer systems and the power grid, according to NASA.

DSCOVR won't just be used to monitor space weather. The satellite will also have some climate-monitoring duties, beaming back data about ozone and aerosol amounts, cloud height, ultraviolet radiation and other information gathered by its Enhanced Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC). The EPIC instrument — a carryover from the original Triana mission — will also be able to photograph the entire sunlit side of Earth from DSCOVR's point in orbit, according to NASA.

Another science instrument, called the National Institute of Standards & Technology Advanced Radiometer (NISTAR), will monitor Earth's radiation.

DSCOVR's mission is scheduled to last two years, but the spacecraft does have enough fuel onboard for five years, NASA officials have said.

Editor's Note: This story was updated at 7:45 p.m. EST to include information about the Falcon 9 stage's soft ocean splashdown.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.