Pioneer 10: Greetings from Earth

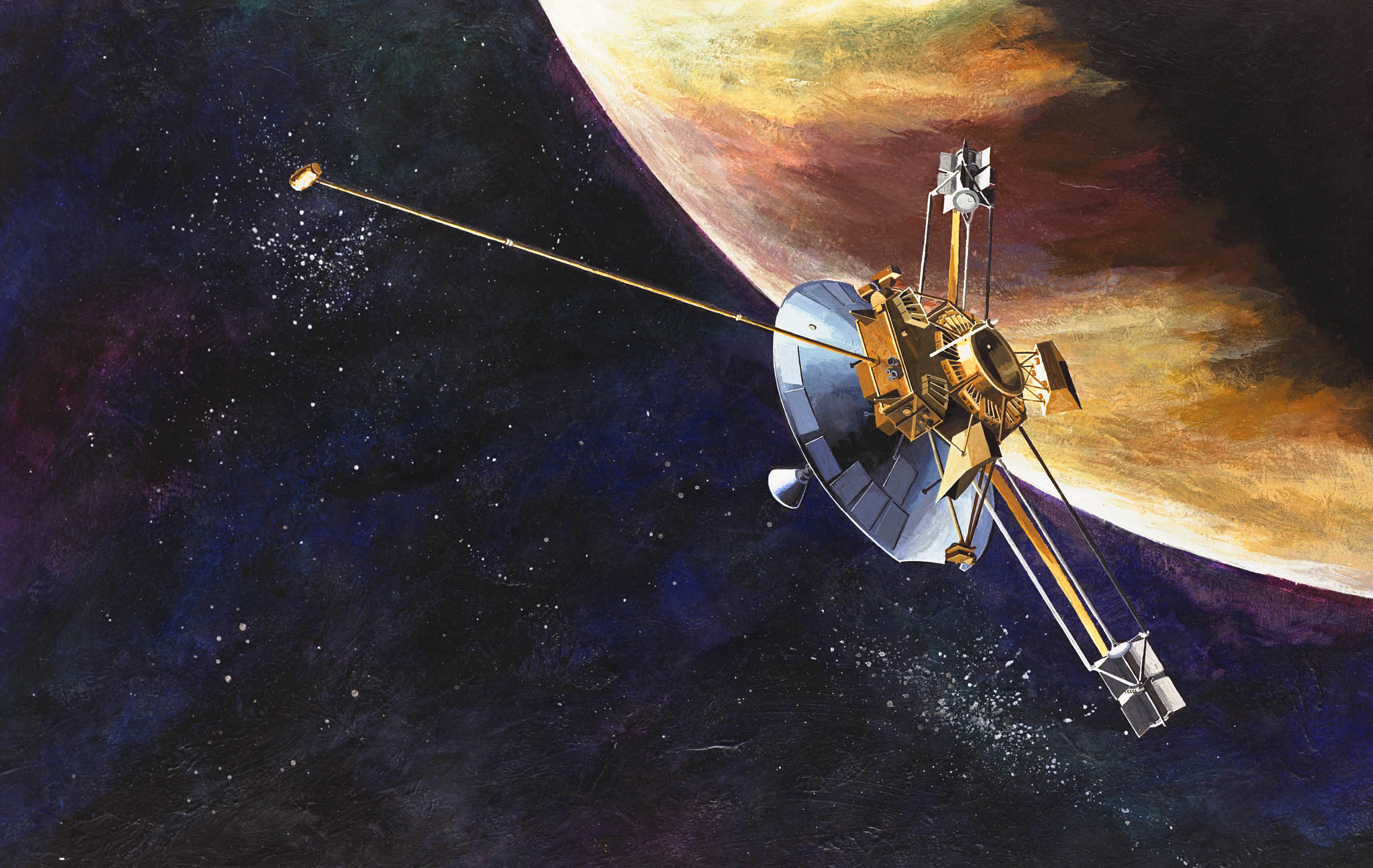

Pioneer 10 was a breakthrough mission, accomplishing several firsts among spacecraft. It was the first to fly beyond Mars, the first to fly through the asteroid belt, first to swing by the planet Jupiter, and first to leave the solar system. Along the way, the spacecraft even generated a mystery of its own – the Pioneer Anomaly – that took decades for scientists to solve.

Thanks to Pioneer 10's pictures, the planet Jupiter and its moons, which were formerly only small circles in a telescope, became large, vibrant worlds in the eyes of scientists. For decades after those images beamed back to Earth, Pioneer 10 kept going. It sent valuable scientific data about the sun and cosmic rays before its signal became too faint for Earthlings to hear.

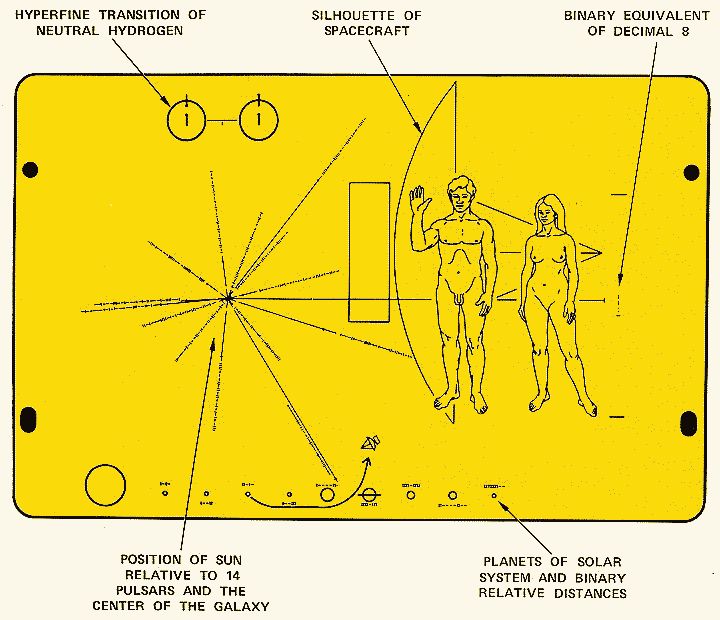

Pioneer 10 also carries a plaque with a message to any intelligent life it might encounter on its journey. The Pioneer plaque includes diagrams of Earth's location and drawings of a man and a woman.

Instruments and art

Launched on March 2, 1972, Pioneer 10 was the latest in a series of missions to explore space, which was still a very new frontier at the time. The earliest Pioneers aimed for the moon, while later generations forged farther and farther into space.

This spacecraft, powered by four radioisotope thermoelectric generators, measured 9.5 feet (2.9 meters) long and weighed 570 pounds (258 kilograms). Among the instruments and camera equipment on board, Pioneer also carried something special: a six- by nine-inch (15.2 by 22.8 centimeters) gold plaque.

The plaque depicts two nude figures – a man and a woman – along with diagrams of the solar system and the sun's position in space. It was intended to serve as a map to Earth for any extraterrestrials who might be curious about who made the spacecraft.

Two people designed the plaque: famed television host and astronomer Carl Sagan, and Frank Drake, founder of SETI and author of an equation that measures the likelihood of communicating with intelligent life.

Imaging Jupiter

Pioneer 10's primary target was the planet Jupiter. It launched from Earth on an Atlas-Centaur three-stage launcher, intended to boost the spacecraft to 32,400 mph (52,142 kph). Sailing away from Earth faster than any spacecraft before it, Pioneer soared by the moon just 11 hours later and made it past Mars in only three months.

Perhaps Pioneer's most dangerous phase was the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, which it reached on July 15. Pioneer faced the risk of colliding with bits of asteroids, anywhere from the size of a small particle to rocks as big as the state of Alaska, according to NASA. But it made it safely to the other side and reached Jupiter on Dec. 3, 1973.

Pioneer 10 was just intended to be a scout for future missions, so its stay at Jupiter was brief. It came within 81,000 miles (130,000 kilometers) of the surface as it sailed past. Pictures beamed back to Earth revealed Jupiter as a liquid giant, while other instruments recorded information on Jupiter's radiation belts and magnetic fields.

The spacecraft also sent back snapshots of some of Jupiter's moons. Although the shots were taken from a distance, scientists could pick out shadows and featureson Europa, Ganymede, Io and Callisto. It was incredible resolution compared to the almost 400 years of observations previously done through telescopes.

On through the outer solar system

Pioneer's story does not end there. For about a quarter-century, the little spacecraft flew farther and farther away from Earth and continued producing science. It measured particles streaming from the sun, and cosmic rays incoming from outside the solar system.

Along with sister ship Pioneer 11, the spacecraft also embroiled scientists in an intergalactic mystery. For decades, NASA was puzzled as to why the two probes travelled 3,000 miles (4,828 km) less than projected, every single year.

Dubbed the "Pioneer Anomaly," it was only in 2012 that NASA found out what happened: heat flowing through the spacecrafts' power systems and instruments was pushing back on the Pioneers as they moved out of the solar system.

NASA concluded Pioneer's science mission on March 31, 1997, but kept track of the spacecraft through the Deep Space Network. Obtaining its signal was used as training for flight controllers looking to get data from the Lunar Prospector mission, which flew for 19 months before being deliberately crashed into the moon's surface in 1999.

Pioneer 10 last sent data back to Earth on April 27, 2002. Its decaying signals were just too faint for NASA's antennas to pick up anymore.

As far as we know, the spacecraft sails on. NASA warmly refers to Pioneer 10 as a "ghost ship" of the outer solar system as the spacecraft coasts in the general direction of Aldebaran – the eye of the bull in the constellation Taurus.

Residents of that region of space will need to be patient if they want to see Pioneer 10. NASA expects it will take the spacecraft 2 million years to traverse the 68 light-years of space to Aldebaran.

— Elizabeth Howell, SPACE.com Contributor

Related:

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.