Discoverer of Lucy asteroid mission's namesake fossil excited to watch Saturday launch

From a 3-million-year-old fossil to a brand-new NASA mission.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

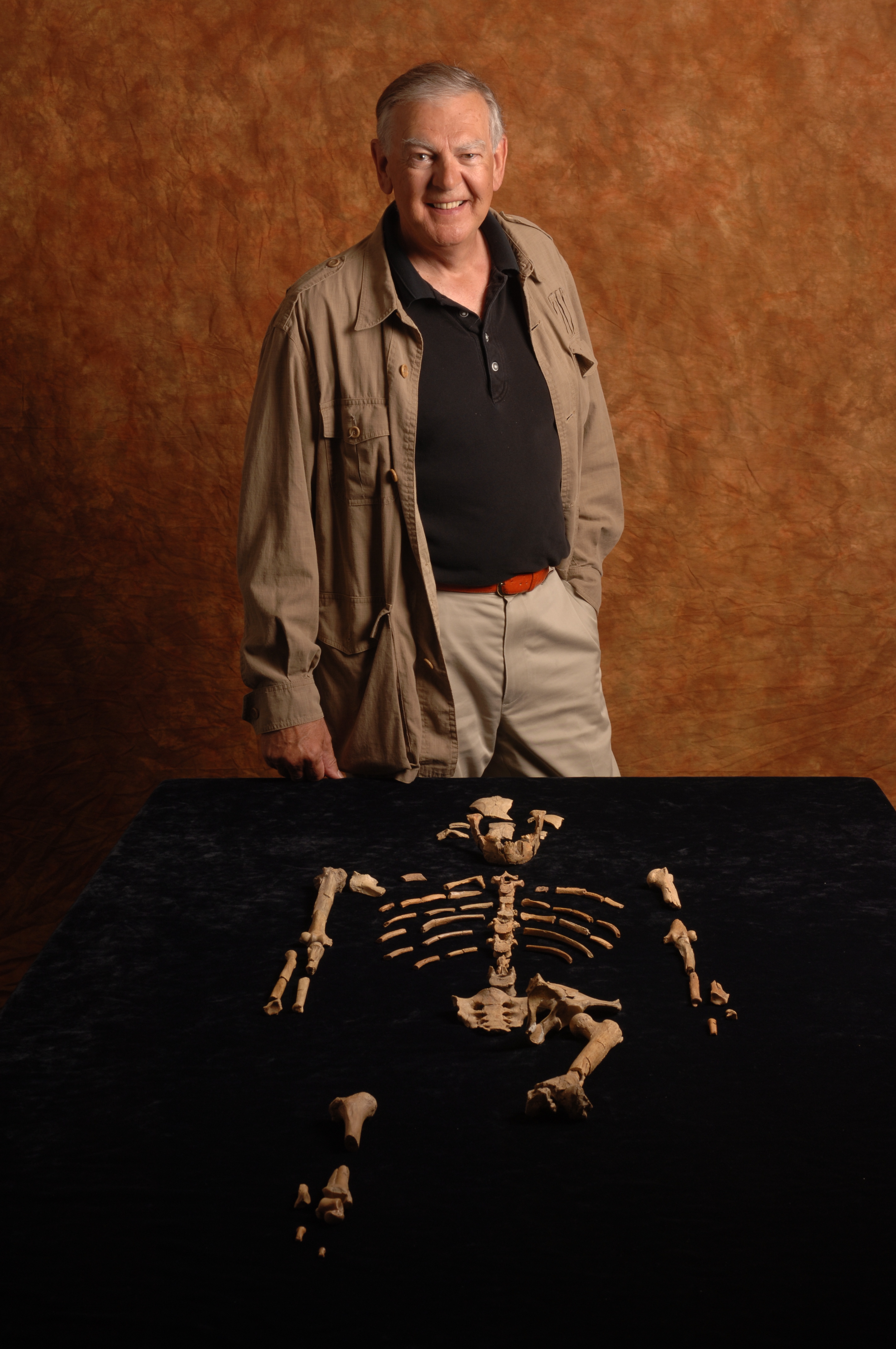

Decades ago, Donald Johanson found fossils of an early hominin that would rewrite scientists' understanding of our species. This weekend, he'll see a spacecraft named for the discovery blast off Earth.

Johanson, a paleoanthropologist at the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University, made his landmark discovery in 1974. In northern Ethiopia, he found the fossilized remains of a 3.2-million-year-old relative of humans; the team nicknamed the find Lucy.

Decades later, when scientists were developing the idea for a spacecraft to visit the Trojan asteroids — "fossils" of the solar system — they decided to name the mission Lucy. On Saturday (Oct. 16), the Lucy spacecraft will blast off Earth, and Johanson will be on the scene at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station for his first-ever rocket launch. You can watch it live here and on the Space.com homepage, courtesy of NASA TV. Liftoff is set for 5:34 a.m. EDT (0934 GMT).

Article continues belowHe told Space.com that the opportunity is particularly exciting because, even as he was becoming more interested in anthropology, he was fascinated by the stars; he even served as president of his high school's astronomy club. "I'm a guy who grew up with Sputnik and the first Americans in space and followed these missions over the years, and so I'm enormously excited to be there," he said.

Related: NASA's Lucy asteroid mission will explore mysteries of the early of solar system

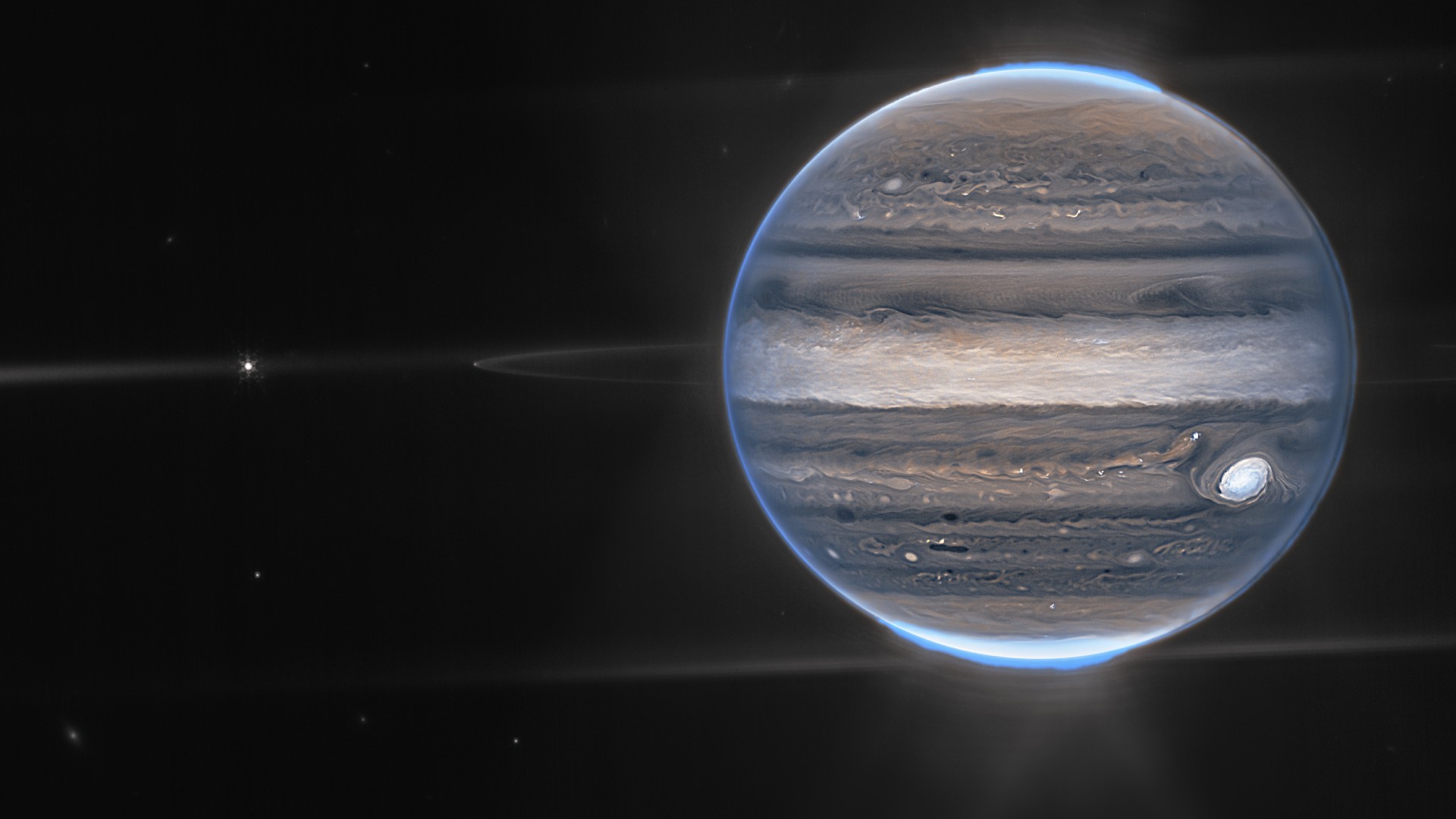

He said he still picks out bright Jupiter in the skies above his house, but it feels a little different, knowing that a mission named for his discovery will be on its way to the planet's companions soon.

"I don't think I'll ever be able to look up at Jupiter again the same way I did before," Johanson said. "That, for me, is something that was utterly and totally unanticipated in my life," he said of the mission connection.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Out of the past

Johanson was fascinated by the long history of humans beginning as a young teenager, as he read about the theory that humans and African apes are closely related.

"I thought, 'Well, how very, very cool this is,'" he said. "When I was 13 years old, that just set my mind on fire." He decided to become an anthropologist, and by 1970, he was a graduate student visiting a field site in southern Ethiopia. "I found that I really loved being in the field, I loved being in Africa. It was as if this was my calling," he said.

Within two years, Johanson was conducting a preliminary survey of the site in Hadar in northern Ethiopia where, another two years later, he would make the discovery for which he is famous. Searching the area for fossils, he spotted what turned out to be part of an armbone. Nearby were other fragments, including teeth and pieces of skull.

Four years later, Johanson and his colleagues told the world that those fossils, and about 300 other pieces found at the site, belonged to a new species of hominin. They called the species Australopithicus afarensis, but what truly caught on was the nickname a team member gave to those first-discovered bones: Lucy, because the scientists had listened to The Beatles' hit song "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" during the dig.

Lucy took the world by storm because the discovery represented not just a new human relative, and a then-rare hominin fossil more than 3 million years old, but also proof that early relatives of humans walked on two feet, even before their brains began to grow. Johanson believes Lucy's species may even be an ancestor of our own genus, Homo.

Across the solar system

The Trojan asteroids, which clump ahead of and behind Jupiter in its orbit, have essentially been untouched since arriving at their stations, since the massive planet tugs away objects that could interfere.

"If you put an object there early in solar system history, it's been stable forever, so these things really are the fossils of what planets formed from," Lucy principal investigator Hal Levison, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said during a prelaunch news conference held on Wednesday (Oct. 13).

As Levison and his colleagues were pulling together the idea of a spacecraft that would explore these solar system fossils, they thought of Lucy's impact on how we understand the evolutionary story of humanity as inspiration of sorts. "Our mission is to find out basically how the solar system evolved, and so giving credit to the fossil seemed appropriate to us," Levison said.

Johanson had kept enough interest in space to know what the Trojans were and to appreciate the comparison, he said.

"Like Lucy told us about the origins of ourselves, this mission, we hope, will tell us about the origins of our solar system, and I was really completely blown away by this," he said. The team also named the main-belt asteroid that Lucy will fly past in 2025 for the anthropologist. "This was just an overwhelming connection for me between discovery and the unexpected."

In July, Johanson was able to meet mission team members and see the nearly completed Lucy spacecraft in a clean room at Lockheed Martin, which built the probe. Seeing the spacecraft, which measures 46 feet (14 meters) across when its twin solar panels are unfurled, gave him a new appreciation for the complicated logistics of the expeditions of planetary scientists, he said.

"You think that was difficult, Don, for you to get Land Rovers ready, and to go into the field and buy all the supplies you needed for these desolate sites in Ethiopia where I've been working for so many years, and all of the planning and so on that goes into a major expedition like we had in Ethiopia," he said. "But my gosh, this is huge."

Bridging time and space

On Saturday, Johanson will join a select group to watch the rocket carrying that spacecraft blast off Earth, the beginning of a 12-year journey through space that links the future of science with the ancient roots of humans and the solar system alike. He said it's given him a new perspective on the future.

"I've been so focused on the past, my professional life has been really focused on where we came from and how we got to be who we are today," he said. And in the present, he says, "our planet is undergoing a number of significant challenges, many of which of course we brought on ourselves."

Against that background, he said, his new tie to spaceflight gives him hope.

"It becomes almost a metaphor for me of, why can't we take a step back and look at the uniqueness of who we are and what this planet is and come together, taking our responsibilities more seriously, so that there'll be people long in the future who will be exploring other parts of the universe?" he said. "For me, it's a very positive look at the endless opportunities that humans have, and the endless creativity that we have because of this remarkable brain we have."

It's a brain in sharp contrast to the one that millions of years ago was tucked inside a 3-foot-tall (1 m) hominin's skull, the fragments of which Johanson would go on to discover.

"What an exciting opportunity for someone who — of course, she'll never know about it, naturally — but for a woman who walked anonymously on a beach 3.2 million years ago and got arrested in suspended animation for all that time, has now kind of been re-animated," Johanson said. "And now as a namesake, she's going to take a mission to make new discoveries about our solar system. There's something very magical about that whole connection."

Lucy the ancient hominin never imagined a rocket or knew that the Trojan asteroids existed, of course — scientists discovered the first of these space rocks only in 1906, according to NASA.

But would Lucy have had any connection to space? Perhaps.

"Without light pollution, the night sky is captivating; it is shimmering with light," Johanson said, adding that he thinks hominins must have at least subconsciously noted a difference in the sky between a full moon and a crescent, for example. "Whether or not they noticed these things or not, we can't be certain. But I guess I kind of like to think maybe they did."

Lucy will launch on Saturday (Oct. 16) at 5:34 a.m. EDT (0934 GMT) from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket. You can watch the launch live at Space.com courtesy of NASA, with coverage starting at 5 a.m. EDT (0900 GMT).

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.