China's Chang'e Program: Missions to the Moon

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

For many space enthusiasts, the Chinese space program's lunar flights have been thrilling to watch. More than a decade ago, China launched the first of its robotic Chang'e missions, and the country has consistently built up ever-greater capabilities as it targets the Earth's natural satellite. In Chinese mythology, Chang'e was a beautiful young girl who took an immortality pill and then flew to the moon, where she became the moon goddess. Chang'e is a fitting name for a series of robots that have gazed down upon our planet from far above.

The Chang'e program began on Oct. 24, 2007, when a Long March 3A rocket launched the Chang'e-1 probe into a polar lunar orbit. The spacecraft circled between 62 and 124 miles (100 and 200 kilometers) high above the lunar surface, bouncing microwave signals off the surface to produce the most high-resolution images ever made up to that point. In addition to mapping features on the moon, Chang'e-1 surveyed the lunar soil for the element Helium-3, which could one day power nuclear reactors; and determined the distribution of other potentially useful resources, according to its mission designers.

Chang'e-1 carried with it 30 "moon tunes," among them Chinese folk songs and China's national anthem. The mission cost 1.4 billion yuan ($180 million) and operated for two years. At the end of its lifetime, the probe was deorbited and crashed into the lunar surface.

A year later, the Chinese space agency sent a follow-up mission named Chang'e-2 to the moon, which produced even more spectacular maps of the lunar surface. The spacecraft's main goal was to scout out locations for China's subsequent lander, but it also accomplished a number of other remarkable feats.

After wrapping up its primary mission, Chang'e-2 departed lunar orbit and flew to the Earth-sun L2 Lagrange point, where the gravitational pull of the Earth and sun just about cancels out. In doing so, the Chinese space agency became only the third agency to visit this point, where it demonstrated deep-space communications and tracking for future missions. In April 2012, the spacecraft then ventured off to conduct a flyby of asteroid 4179 Toutatis, getting as close as 2 miles (3.2 km) away, according to China's Xinhua state news service. The probe is expected to return closer to Earth sometime around 2029.

China made history on Dec. 4, 2013, with a successful landing for the Chang'e-3 mission. The touchdown in Mare Imbrium, an ancient volcanic plain, represented the first soft landing on the moon in nearly 40 years — a feat last accomplished by the Soviet Union in 1976. Chang'e-3 carried the six-wheeled, solar-powered Yutu rover — named for the pet rabbit of the goddess Chang'e — which rolled out onto the lunar surface and snapped spectacular photos.

"The bad news is, I was supposed to go to sleep this morning, but before I went to sleep, my masters found some mechanical control abnormalities," the first-person posting read. "But if this trip is to end prematurely, I'm not afraid. I'm just in my own adventure story, and like any protagonist, I encountered a bit of a problem. Goodnight, Earth. Goodnight, humans."Yutu won the hearts and minds of people all over the world by surviving its first long, harsh lunar night, which lasts two weeks, though it began encountering technical problems after its second night. An anonymous user of the Chinese social media platform Weibo created a narrative told from the rover's perspective following the malfunctions.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Yutu stopped moving after that, though its instruments continued to function for two and a half years, sending back valuable information to scientists. The robot finally bit the lunar dust in 2016.

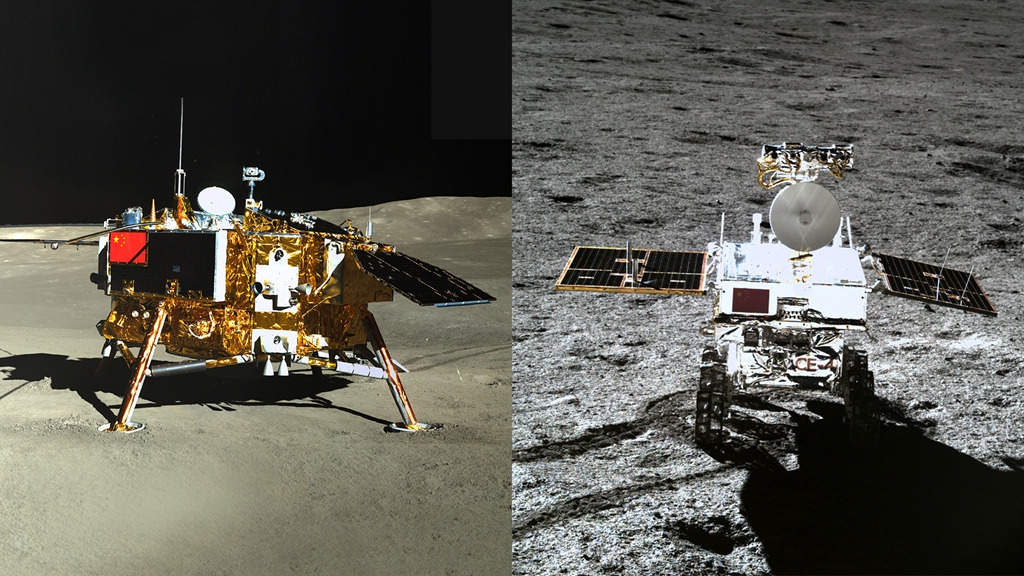

China's fourth moon probe, the Chang'e-4 lander, which arrived on the far side of the moon on Jan. 2, 2019, is currently creating a great deal of excitement: It is the first spacecraft to ever land on the moon's space-facing hemisphere. The robot touched down at 177.6 degrees east longitude and 45.5 degrees south within Von Kármán crater, according to an announcement from the China National Space Administration (CNSA). Von Kármán is located inside of the South Pole-Aitken basin, the largest and oldest impact crater on the moon, which has never been explored. [Photos from the Moon's Far Side! China's Chang'e 4 Lunar Landing in Pictures]

Landing on the lunar far side is difficult because there is no way to transmit signals directly to Earth. Prior to Chang'e-4, the Chinese space agency launched the Queqiao relay satellite into lunar orbit, which enables communications to any point on the surface. Queqiao means "Bridge of Magpies." It refers to a Chinese folktale about magpies forming a bridge with their wings to allow Zhi Nu, "the seventh daughter of the Goddess of Heaven," to reach her husband, according to NASA.

Chang'e-4 brought with it a successor to the Yutu rover, fittingly named Yutu 2. The lander also carried a small enclosed experiment with living organisms, including cotton seeds, fruit fly eggs and yeast. The cotton seeds sprouted, becoming the first plants to germinate on another world. Unfortunately, a day later, the probe entered its first lunar night and, needing to conserve power, did not use its battery to keep the organisms warm. When temperatures inside the canister plunged to minus 62 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 52 degrees Celsius), all of the plants died.

The next in line for China's lunar accomplishments is the Chang'e-5 mission, which will land near Mons Rümker, a mountain overlooking a huge basaltic lunar plain called Oceanus Procellarum. Chang'e-5 will bring back samples from the lunar surface — the first new material from our natural satellite in more than four decades. Scientists are eager to get new samples, which will join material returned by Apollo astronauts and Soviet robots, and hopefully help answer questions about the formation of both the moon and Earth. Chang'e-5 is expected to launch by the end of this year.

Another sample-return mission, Chang'e-6, will return to the South Pole-Aitken basin and aim to bring back rocks from the ancient impact, according to a press conference given by the State Council Information Office of China (SCIO). Such material would represent some of the oldest samples taken from the lunar surface, giving researchers unparalleled insights into the solar system's early days.

Chang'e-7 will soon follow and conduct comprehensive surveys around the moon's south pole, studying terrain and landforms. The final currently planned mission is Chang'e-8, which is expected to test key technologies that will lay the groundwork for a crewed research base on the moon. The Chinese space agency has yet to announce the exact timeline of these future missions.

Additional resources:

- Check out NASA's images of the Chang'e 3 landing site.

- Read more about the Chang'e program from the Hong Kong Science Museum.

- Watch this video about the first three phases of the Chang'e program from Beijing Review.

Editor's Note: This article was updated on Feb. 4, 2019 to reflect a correction. The original article incorrectly stated that "The East is Red" is China's national anthem.

Adam Mann is a journalist specializing in astronomy and physics stories. His work has appeared in the New York Times, New Yorker, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike. Follow him on Twitter @adamspacemann or visit his website at https://www.adamspacemann.com/.