Report: Columbia Astronauts Killed in Seconds

This story was updated at 2:14 pm EST.

The seven astronauts killed during the 2003 loss of NASA's space shuttle Columbia survived less than a minute after their spacecraft began breaking apart, according to a new report released Tuesday that suggests changes to astronaut training and spacecraft cabin design.

The 400-page "Columbia Crew Survival Investigation Report" released today states that Columbia's ill-fated crew had a period of just 40 seconds between the loss of control of their spacecraft and its lethal depressurization in which to act on Feb. 1, 2003.

The crew's response was hampered by delays in donning their re-entry pressure suits, which ultimately would not have saved them during the searing plunge into the atmosphere anyway.

"The Columbia depressurization event occurred so rapidly that the crew members were incapacitated within seconds, before they could configure the suit for full protection from loss of cabin pressure," the report states. "Although circulatory systems functioned for a brief time, the effects of the depressurization were severe enough that the crew could not have regained consciousness. This event was lethal to the crew."

In-depth analysis

Returning to Earth aboard Columbia were commander Rick Husband, pilot Willie McCool, mission specialists Kalpana Chawla, Laurel Clark, Michael Anderson, David Brown and Ilan Ramon, Israel's first astronaut. Exposure to high altitude and blunt trauma caused their deaths, the report states.

One of Columbia's STS-107 crew members was not wearing a pressure suit helmet and three astronauts had not put on their spacesuit gloves, according to the report. At no point did crew error contribute to the loss of Columbia, which was not a survivable event, the report states.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The design of Columbia's seats, too, decreased the crew's chances of survival as their restraints did not lock in place, subjecting the astronauts to extreme trauma from rotational forces. Their helmets were not head-conforming, resulting in injuries and lethal trauma, the report states.

The investigation "was performed with the belief that a comprehensive, respectful investigation could provide knowledge that would improve the safety of future space flight crews and explorers," said the team of astronauts, pilots and engineers that compiled it.

The report found five separate lethal events that occurred during Columbia's descent. It calls for enhanced astronaut training to help spacecraft crewstransition from emergency response to survival mode. It also recommends that NASA design the seats and pressure suits for future spacecraft with loss of vehicle control in mind.

Current astronaut pressure suits, for example, require astronauts to manually deploy their parachute during an emergency escape. Modifying the system to automatically close visors or deploy a parachute could help an unconscious astronaut's chances if they survived a spacecraft's catastrophic descent.

Tragic loss of Columbia

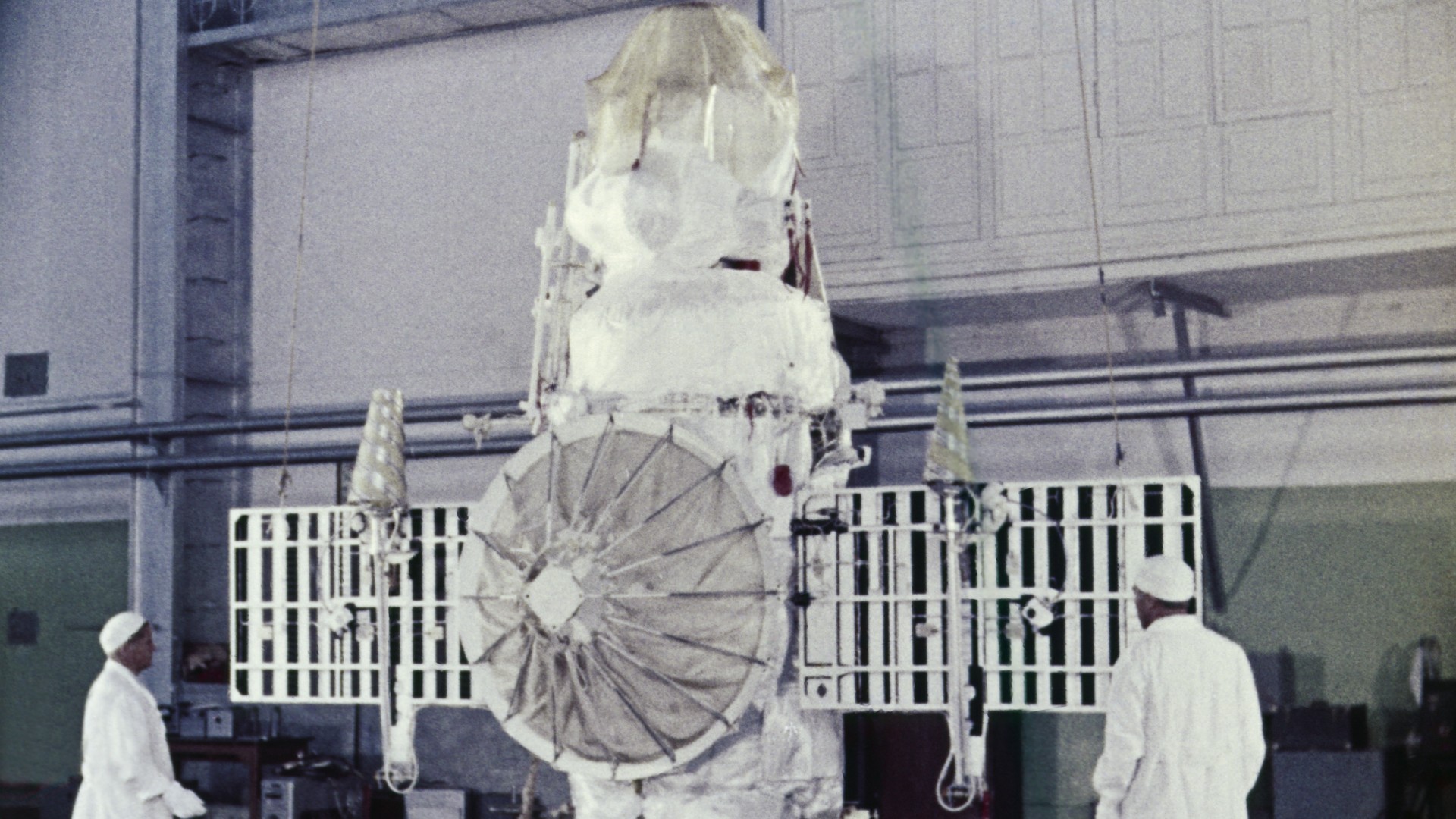

Columbia broke apart during reentry while returning to Earth after a 16-day science mission. Investigators later found that a piece of shuttle fuel tank foam insulation punched a hole in the heat shielding that lined Columbia's left wing edge during its Jan. 16 launch. The damage allowed superheated atmospheric gases to penetrate the spacecraft's wing during re-entry, destroying the shuttle and killing the crew 16 minutes before their planned landing.

The shuttle was flying about 200,000 feet (nearly 38 miles or 60 km) above Earth at a speed of about 12,500 mph (20,120 kph) when flight controllers received their last communications from the shuttle. That call came at about 8:59 a.m. EST (1359 GMT).

Once the spacecraft's cabin began breaking apart, Columbia's crew had no protection against the searing heat of re-entry outside, the report states, adding that the bright orange pressure suits could not withstand such conditions.

"The ascent and entry suit had no performance requirements for occupant protection from thermal events," the report states. "The only known complete protection from this event would be to prevent its occurrence."

Following the loss of Columbia, NASA halted shuttle flights for more than two years and developed new heat shield inspection and repair tools for astronauts in orbit.

NASA resumed space shuttle flights in 2005 and has since flown 11 missions to the International Space Station.

The agency plans to fly nine more shuttle flights before retiring its three-orbiter fleet in 2010 to make way for its replacement, the capsule-based Orion spacecraft and its Ares 1 booster. That spacecraft is expected to begin operational flights in 2015.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.