NASA's Mars Program in Disarray

HOUSTON, Texas - The robotic Mars program is sort of a planetary Dead Man Walking these days, as scientists debate what missions should be next on the agenda and how Mars should compete for funding with other compelling destinations ranging from our own moon to potentially life-harboring moons in the outer solar system.

Long-time Mars researcher Chris McKay of NASA's Ames Research Center thinks it's time to recast the exploration agenda for the red planet.

"The NASA Mars program is at a turning point," McKay argues in the April edition of The Mars Quarterly, a Mars Society newsletter. A trio of factors are converging that should prompt a reset of the space agency's pinball wizard of a red planet exploration program, he writes:

- The Mars Science Laboratory was recently delayed to 2011 and has seen its price tag soar to roughly $2.2 billion.

- Costs of Mars robotic missions will continue rising as larger, more competent missions are proposed. Mars missions have moved into the cost category of the "flagship" missions to the outer solar system.

- Mars as the primary astrobiology target is now in competition with other worlds – particularly Saturn's moons Titan and organics-spitting Enceladus, McKay argues. While the search for a second genesis of life in our solar system may still drive missions, he states that these missions may not be to Mars.

This week at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference here, researchers are expected to debate the plans for Mars vs. other destinations. And there are no shortage of viewpoints.

"It's fair to say that the Mars program is in disarray," said Bruce Jakosky, a noted Mars researcher and astrobiologist at the University of Colorado in Boulder. "NASA is still working to sort out the Mars Science Laboratory problems and from where the money will come to pay for the overruns."

Jakosky disagrees that the program needs a complete overhaul, however.

Success or failure so far?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

McKay salutes the data gleaned by orbiters, landers and rovers – information that collectively has added to our knowledge of Mars, "even if they have not provided much additional evidence supporting the possibility of life at the present or in the past."

Taken all together, McKay argues, "the exploration Mars over the decade since the start of the Mars program has not strengthened our hope that life might have been present... in fact [it] has diminished it."

McKay believes that for Mars to retain a special place in exploration, the rationale for studying the place is not driven purely by science – astrobiology or planetary. Rather, Mars is the only world for which we can imagine sustained human activity.

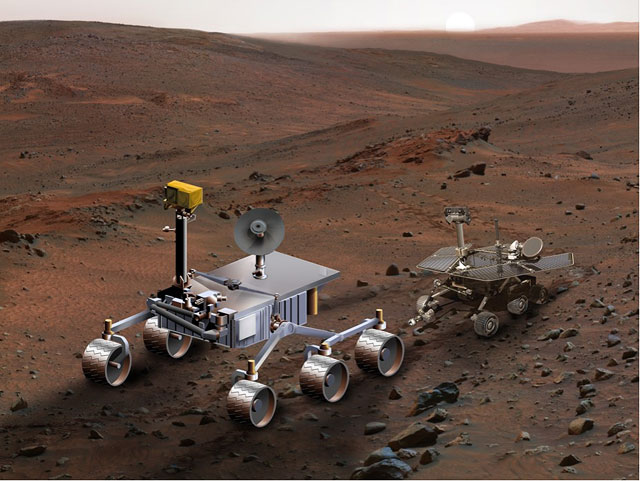

"A vigorous program of robotic exploration is needed to determine if Mars is a world in which humans can live and work and to prepare for human exploration. Orbiters, rovers, drills, and sample return missions are all needed to prepare for human exploration," McKay asserts.

There is no time to lose, argues McKay. "I conclude that Mars should continue to be a special target for robotic exploration precisely because it will be the scene of extensive human exploration in the future."

McKay emphasized to me that his basic point is "for the Mars Program to remain viable, it needs to become part of the Exploration Program ... it needs to focus on paving the way for human exploration. And this means sample return."

Intellectual underpinnings

But does a Mars program tied to a human program become either intellectually more profound or pragmatically more fundable? Not necessarily, argues Jakosky, who is the principal investigator for the recently selected Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution mission (MAVEN).

Slated for launch in 2013, MAVEN would probe the past climate of Mars, including its potential for harboring life over the ages.

Jakosky told SPACE.com that the details of a 2016 mission to Mars are still being worked out – whether it will be an orbiter, collaboration with the European Space Agency, or something else.

"But that doesn't mean that the intellectual underpinnings for the program aren't solid," Jakosky explained. "They've been spelled out clearly for the past decade or more, and the Mars program over that same time has addressed them in a substantive way."

There are a lot of issues to be addressed at Mars, Jakosky continued, and a variety of missions that would do so in significant ways. Each mission depends on the preceding ones..."so it's not a surprise that we continually redefine the directions of the program," he said.

Jakosky's bottom line is that he doesn't agree with McKay's perspective.

Where's the money?

The underlying theme in the Mars program is trying to understand whether there has ever been life, Jakosky said. Closely related to that is what the environmental conditions have been and, in essence, what the history of habitability by microbes has been. Martian conditions generally appear to be capable of supporting life, either today or in the past, he said.

"Nothing we've discovered from the Mars rovers, Phoenix, Odyssey, or Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter suggests that conditions might have been unsuitable for life," Jakosky said. "We're still trying to sort out the relationship between local phenomena as measured on the ground by the rovers and landers and regional- or global-scale characteristics."

The point that the outer solar system should become the intellectual focal point for astrobiology is not a unique perspective, Jakosky observed. "It's arguable that the outer solar system could be an abode for life while Mars might not be."

Jakosky said that an astrobiology mission to the outer solar system would be far more costly than to the inner solar system.

"A shift to the outer solar system in exploring for life would be fatal to the program," he said. "Missions would be way too expensive and a series of missions would take forever."

A case in point is a Europa orbiter mission, costing $2-3 billion or so, "and the science likely would be comparable to what could be done at Mars in a Scout mission at $0.5 billion. Not a reason to not do it – I'm all in favor of a mission like that – but let's keep the costs in proper perspective," he said.

- Video: Next Big Step on Mars, Part 1

- Video: Next Big Step on Mars, Part 2

- Future of Mars Exploration: What's Next?

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than four decades. He is past editor-in-chief of the National Space Society's Ad Astra and Space World magazines and has written for SPACE.com since 1999.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.