'Blinded' Satellite Gains Ground in Radio Interference Battle

A beleaguered European satellite that has been beset bypatchy "blindness" from radio interference appears to be recoveringafter painstaking efforts to reduce signal contamination.

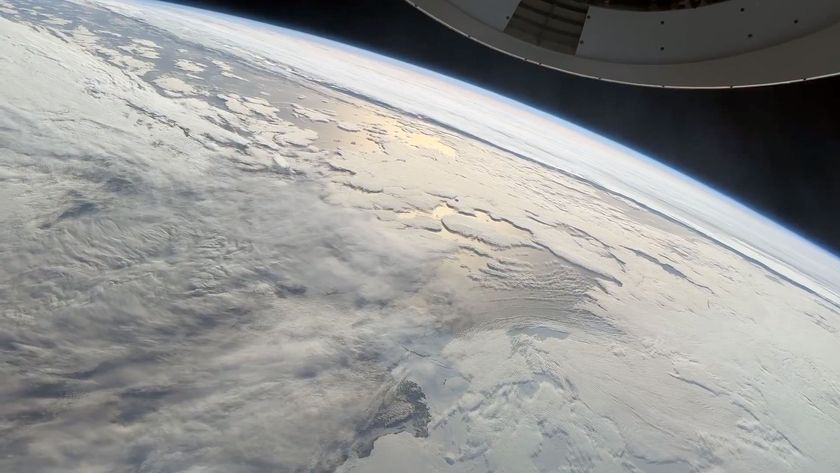

The radio interference is plaguing the European SpaceAgency's SoilMoisture and Ocean Salinity satellite, which launched in November 2009 to studyEarth's water cycle. But shortly after it began transmitting, projectscientists noticed that over certain areas, radio-frequency interference wasbadly contaminating the data.

"At times, this interference was effectively blindingthe instrument, rendering the data over certain areas unusable," ESAofficials said in a Wednesday (Oct. 6) statement.

The unwanted signals have mainly come from TV transmitters,radio links and networks such as security systems. Terrestrial radars appear toalso cause some problems, ESA officials said.

Despite the unwanted signals, the SMOS satellite has managedto meet its scientific goals in areas free of the interference, but in order tomaximize the mission's success, the issues must be resolved, ESA officials said.[Gallery- Spotting Satellites From Earth]

The interference problems experienced by the SMOS satelliteare unrelated to Intelsat's waywardGalaxy 15 satellite, which lost contact with ground controllers in April,and has spent months adrift in orbit with an active payload.??

Satellite's radio interference

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

SMOS is equipped with a passive radiometer that operates inthe L-band of the electromagnetic spectrum. Regulations set by theInternational Telecommunications Union reserve this frequency band for spaceresearch, radio astronomy and a radio communication service between Earthstations and space, known as the Earth Exploration Satellite Service.

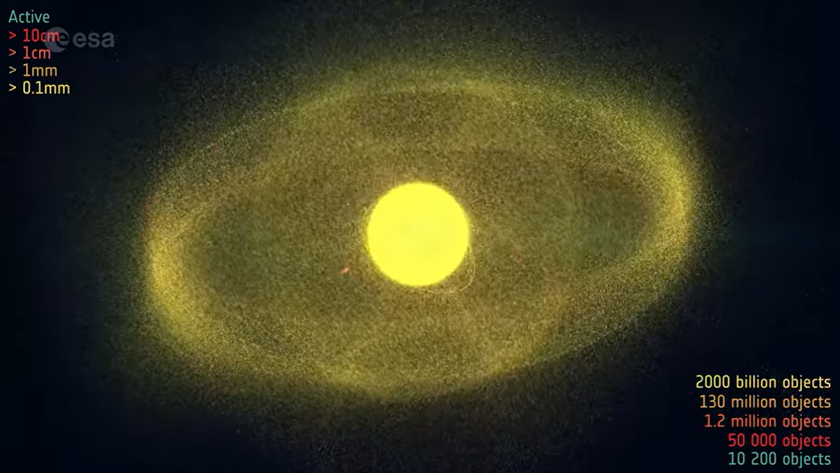

Yet, data from SMOS revealed that there were many incidencesof other signals within this protected band, particularly in southern Europe,Asia, the Middle East and some coastal zones.

"The transmissions contaminating the data were due totwo main reasons: either emissions in adjacent bands that were leaking into theprotected region owing to excessive power levels, or illegal transmissionswithin 1400-1427 MHz," ESA officials said in a statement.?

Space interference battle

In an international effort between the space agency andvarious governments, ESA sought to have the illegal transmissions shut down,and excessive out-of-band emissions reduced.

"The SMOS data are able to show, within a fewkilometers, where the interference comes from," officials said."Knowing the rough locations, ESA has been contacting National SpectrumManagement Authorities to request that they take steps to resolve the issue."

Over the last few months, ESA officials have reported"significant improvement" in the SMOS data.

"While the cooperation between ESA and governmentauthorities continues to be fruitful, the hope is that these cases will lead totighter regulation enforcement," they said.

SMOS is the second Earth Explorer Opportunity mission thatwas developed as part of ESA's Living Planet Program. The satellite is designedto observe ocean salinityand soil moisture. SMOS data will contribute to hydrological studies thatwill improve our understanding of the planet's ocean circulation patterns.

- Images- Spotting Satellites and Spaceships From Earth

- Life'sLittle Mysteries: How Much Junk is in Space?

- ZombieSatellite Galaxy 15 Still Won't Die

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.