Apollo 13: Facts about NASA's near-disaster moon mission

Apollo 13 is famously described as a "successful failure". Learn more about the mission here.

Apollo 13 was NASA's third moon-landing mission, but the astronauts never made it to the lunar surface.

During the mission's dramatic series of events, an oxygen tank explosion almost 56 hours into the flight forced the crew to abandon all thoughts of reaching the moon. The spacecraft was damaged, but the crew was able to seek cramped shelter in the lunar module for the trip back to Earth, before returning to the command module for an uncomfortable splashdown.

The mission stands today as an example of the dangers of space travel and of NASA's innovative minds working together to save lives on the fly. The Apollo 13 mission celebrated its 50th anniversary on April 11, 2020.

Related: NASA's moonwalking Apollo astronauts: Where are they now?

Apollo 13 crew

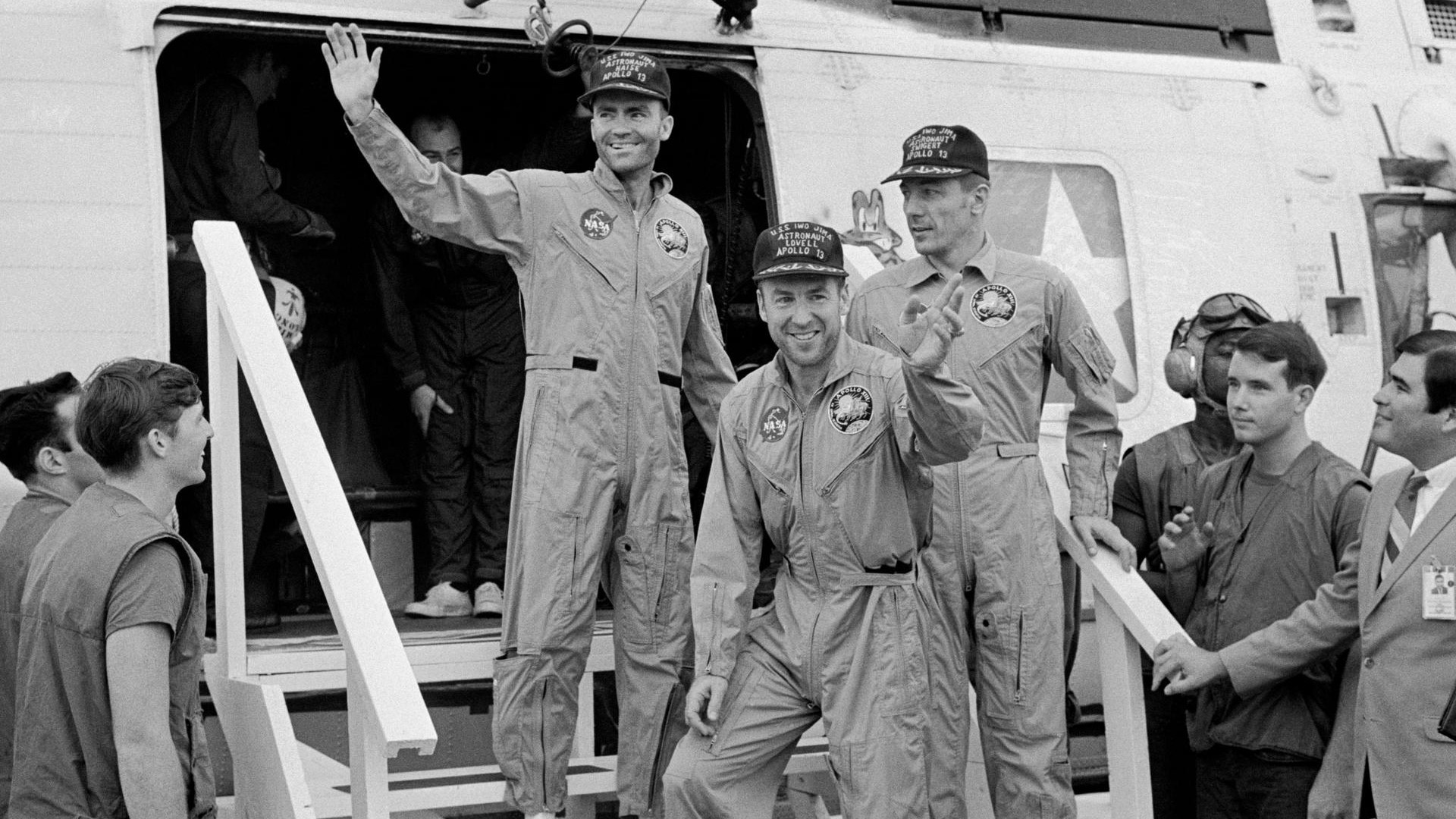

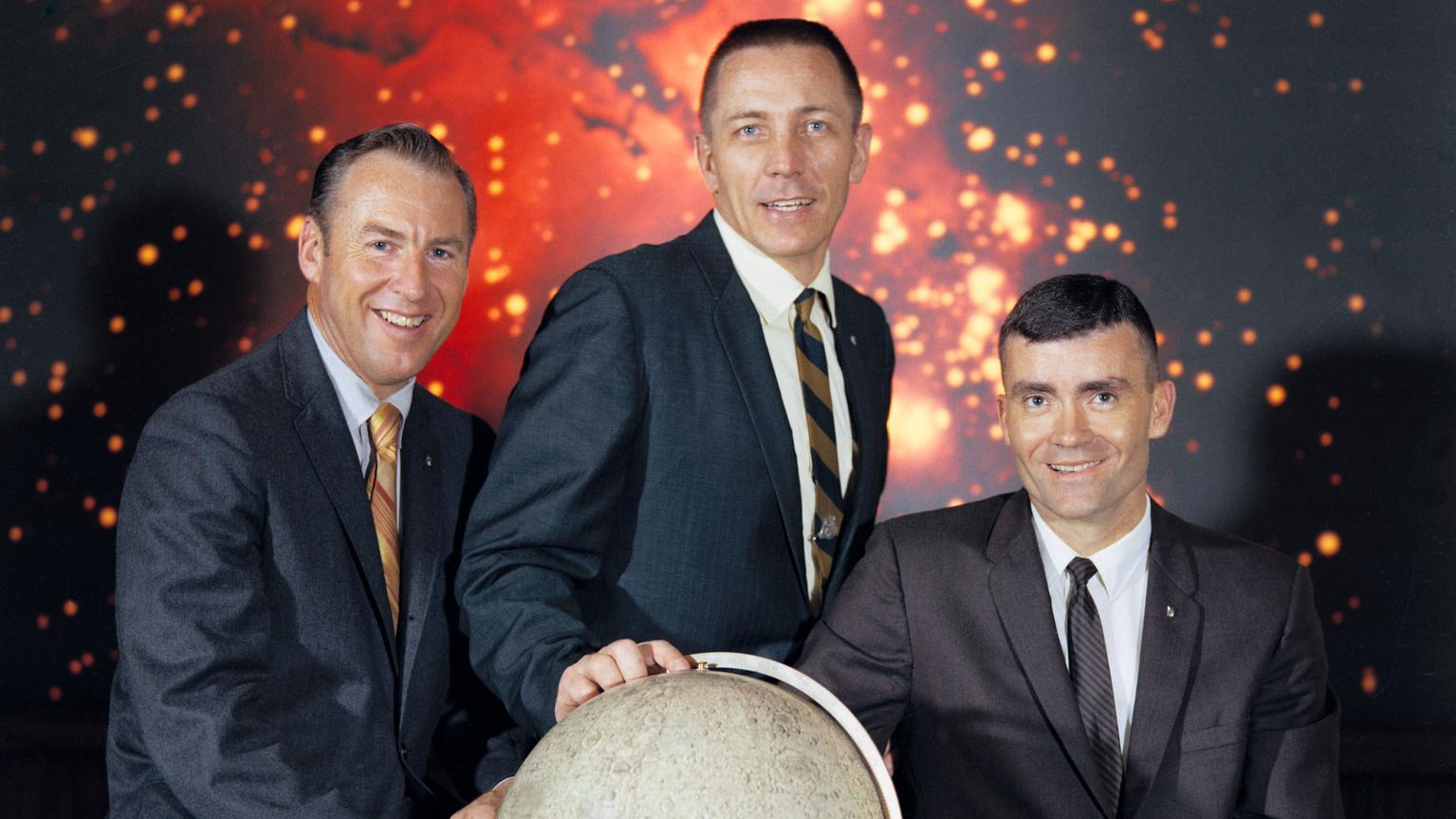

The Apollo 13 astronauts were commander James Lovell, lunar module pilot Fred Haise, and command module pilot John "Jack" Swigert.

At age 42, Lovell was the world's most traveled astronaut when he joined the Apollo 13 mission, with three missions and 572 spaceflight hours under his belt. Lovell participated in Apollo 8, the first mission to circle the moon, and flew two Gemini missions — including a 14-day endurance run.

Prior to the Apollo 13 mission, 36-year-old Haise served as the backup lunar module pilot for the Apollo 8 and Apollo 11 missions. Haise was a fighter pilot in the U.S. Marine Corps before joining NASA as a test pilot. He was selected for the manned space program in 1966, at the same time as Swigert. Apollo 13 was Haise's only trip to space.

Apollo 13 was Swigert's first trip to space, at age 38. He had been part of the support crew for Apollo 7 and was initially Apollo 13's backup command module pilot. He was asked to join the crew 48 hours before launch time after the original command module pilot, Ken Mattingly, was exposed to German measles.

Apollo 13 FAQs

Did the Apollo 13 crew survive?

Yes, though the mission failed to reach the moon, Apollo 13 made it back to Earth successfully and the whole crew — commander James Lovell, lunar module pilot Fred Haise, and command module pilot John "Jack" Swigert — survived.

What happened to the real Apollo 13?

Apollo 13 was NASA's third moon-landing mission but didn't reach the lunar surface. A series of problems plagued the Odyssey spacecraft which was designed to bring them home, causing the crew to abandon all thoughts of reaching the moon.

A fire ripped through one of Odyssey's oxygen tanks and damaged another. Oxygen fed the fuel cells in the spacecraft, so power was also reduced. Fortunately the spacecraft Aquarius — designed to land on the moon — was still in working order. But Aquarius didn't have a heat shield so it would not survive the reentry back to Earth. So the crew crammed themselves into Aquarius — which was designed for two people, not three — and began the long cold journey home. Without a source of heat, cabin temperatures quickly dropped close to freezing. Some food became inedible. The crew also rationed water to make sure Aquarius — operating for longer than it was designed — would have enough liquid to cool its hardware down.

In the hours before splashdown, the exhausted crew scrambled back over to the Odyssey and powered it up.

Thanks to a monumental effort from the crew, mission control and spacecraft manufacturers helping with the mission, Lovell, Haise and Swigert safely splashed down in the Pacific Ocean near Samoa, on April 17, 1970.

How did Apollo 13 get back to Earth safely?

The Apollo 13 crew used their lunar lander — Aquarius — as a makeshift 'lifeboat' to survive the long cold journey back to Earth. It was a rough journey home. The entire spaceflight crew lost weight, and Fred Haise developed a kidney infection. But the small vessel protected and carried the crew long enough to reach Earth's atmosphere. The crew only returned to Odyssey in the hours before splashdown to power it up and begin their reentry to Earth.

Apollo 13: "Houston, we've had a problem"

Apollo 13 launched on April 11, 1970. The Apollo spacecraft was made up of two independent spacecraft joined by a tunnel: orbiter Odyssey, and lander Aquarius. The crew lived in Odyssey on the journey to the moon.

On the evening of April 13, when the crew was nearly 322,000 kilometers (200,000 miles) from Earth and closing in on the moon, mission controller Sy Liebergot saw a low-pressure warning signal on a hydrogen tank in Odyssey.

The signal could have shown a problem, or could have indicated the hydrogen just needed to be resettled by heating and fanning the gas inside the tank. That procedure was called a "cryo stir", and was supposed to stop the supercold gas from settling into layers.

Related: This stunning 4K video re-creates Apollo 13's perilous trip around the moon

Swigert flipped the switch for the routine procedure. A moment later, the entire spacecraft shook. Alarm lights lit up in Odyssey and in Mission Control as oxygen pressure fell and power disappeared. The crew notified Mission Control, with Swigert famously saying, "Houston, we've had a problem." (Note that the 1995 movie "Apollo 13" took some creative license with the phrase, changing it to "Houston, we have a problem" and having the words come out of Apollo 13 commander James Lovell's mouth).

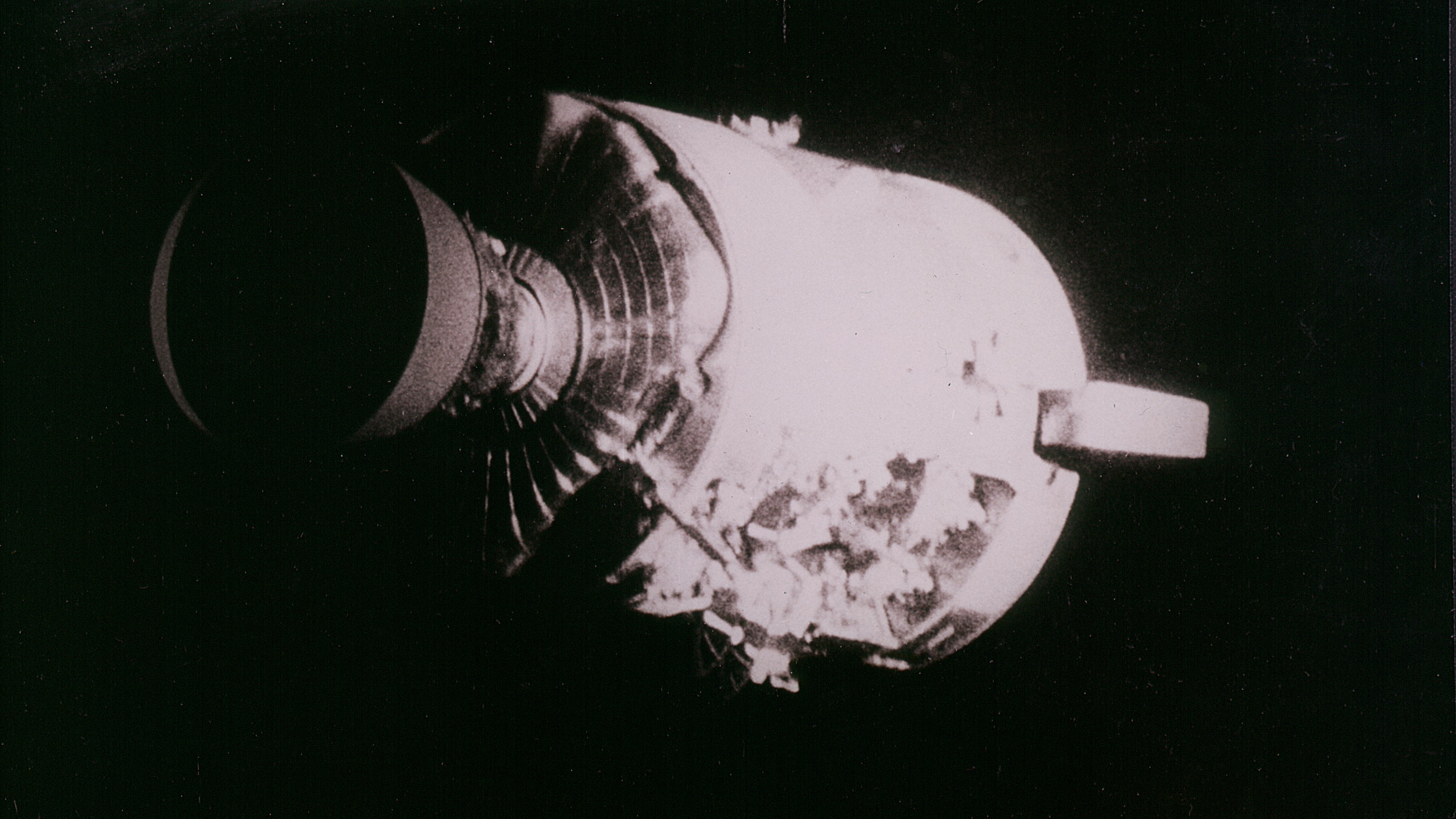

Much later, a NASA accident investigation board determined wires were exposed in the oxygen tank because of a combination of manufacturing and testing errors before flight. That fateful night, a spark from an exposed wire in the oxygen tank caused a fire, ripping apart one oxygen tank and damaging another inside the spacecraft.

Since oxygen fed Odyssey's fuel cells, power was reduced as well. The spacecraft's attitude control thrusters, sensing the venting oxygen, tried to stabilize the spacecraft by firing small jets. The system wasn't very successful given several of the jets were slammed shut by the explosion.

Fortunately for Apollo 13, the damaged Odyssey had a healthy backup: Aquarius, which wasn't supposed to be turned on until the crew was close to landing on the moon. Haise and Lovell frantically worked to boot Aquarius up in less time than designed. Aquarius didn't have a heat shield to survive the drop back to Earth, so as Lovell and Haise got the lunar module up and running, Swigert remained in Odyssey to shut down its systems to conserve power for splashdown.

Apollo 13's cold, miserable trip home

The crew had to balance the challenge of getting home with the challenge of preserving power on Aquarius. After they performed a crucial burn to point the spacecraft back toward Earth, the crew powered down every nonessential system in the spacecraft.

Without a source of heat, cabin temperatures quickly dropped down close to freezing. Some food became inedible. The crew also rationed water to make sure Aquarius — operating for longer than it was designed — would have enough liquid to cool its hardware down. And Aquarius was pretty cramped as it was designed to hold two people, not three.

On Earth, flight director Gene Kranz pulled his shift of controllers off regular rotation to focus on managing consumables like water and power. Other mission control teams helped the crew with its daily activities. Spacecraft manufacturers worked around the clock to support NASA and the crew.

It was a rough journey home. The entire spaceflight crew lost weight, and Haise developed a kidney infection. But the small vessel protected and carried the crew long enough to reach Earth's atmosphere.

In the hours before splashdown, the exhausted crew scrambled back over to the Odyssey and powered it up. The craft had essentially been in a cold water soak for days and could have shorted out, but thanks to safeguards put in place after the Apollo 1 disaster, there were no issues.

Lovell, Haise and Swigert safely splashed down in the Pacific Ocean near Samoa, on April 17.

Apollo 13's legacy

Numerous design changes were made to the Apollo service module and command module on subsequent missions in the Apollo program. According to former mission controller Sy Liebergot in an article by collectSPACE the changes included:

- Another cryo oxygen tank that could be isolated to only supply the crew.

- Removing all cryo tank fans and wiring.

- Removing the thermostats from cryo tanks, and changing the type of heater tube.

- Adding a 400-amp-hour lunar module descent stage battery.

- Adding water storage bags to the command module.

As for the astronauts, Haise was assigned to command the Apollo 19 moon mission. However, it and two other missions were canceled after NASA's budget was cut. He later piloted the space shuttle Enterprise during its test flights.

In 1982, Swigert was elected to Congress in his home state of Colorado. However, during the campaign, he was diagnosed with bone cancer, and he died before he could be sworn in.

In 1994, Lovell and journalist Jeffrey Kluger co-wrote a book about Lovell's spaceflight career that primarily focused on the events of the Apollo 13 mission. The book, "Lost Moon: The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13" (Houghton Mifflin, 1994), spurred the 1995 movie "Apollo 13," starring actor Tom Hanks. The movie won two Academy Awards and was filmed in cooperation with NASA.

The agency gave the movie crew access to the 1960s-era Mission Control in Houston to reconstruct the site as a set, and also let the actor "astronauts" fly aboard NASA's Vomit Comet airplane to simulate weightlessness. Lovell made a cameo at the end of the film as the captain of the U.S.S. Iwo Jima; Marilyn Lovell and Gene Kranz made short appearances as well, according to the Internet Movie Database.

Other biographical accounts of the Apollo 13 mission include Liebergot and David Harland's "Apollo EECOM: Journey of a Lifetime" (Collector's Guide Publishing, 2003) and Kranz's "Failure Is Not An Option" (Simon & Schuster, 2000). Several non-fiction books have also examined Apollo 13, such as Andrew Chaikin's "A Man On The Moon" (Penguin Books, 1994), which included interviews with all of the surviving Apollo astronauts.

Additional resources

Read more about Apollo in this in-depth article from NASA. Explore the "successful failure" mission with this virtual exhibit from Space Center Houston. Discover other great stories from the Apollo missions with the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum.

Bibliography

"Space is hard - mission control after Apollo 13". 17, April. 2020. ESA

Lovell, Jim, and Jeffrey Kluger. Apollo 13. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2006.

Kauffman, James. "A successful failure: NASA’s crisis communications regarding Apollo 13." Public Relations Review 27.4 (2001): 437-448.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

-

Eva Braun During the saving mission, the crew was calm despite the danger of the situation, the conditions, and the difficult task that faces them, and the captain of the mission would become part of other NASA missions.Reply