Poppy Northcutt, the Only Woman in Mission Control, Recalls Challenges of Bringing Apollo Astronauts Home

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

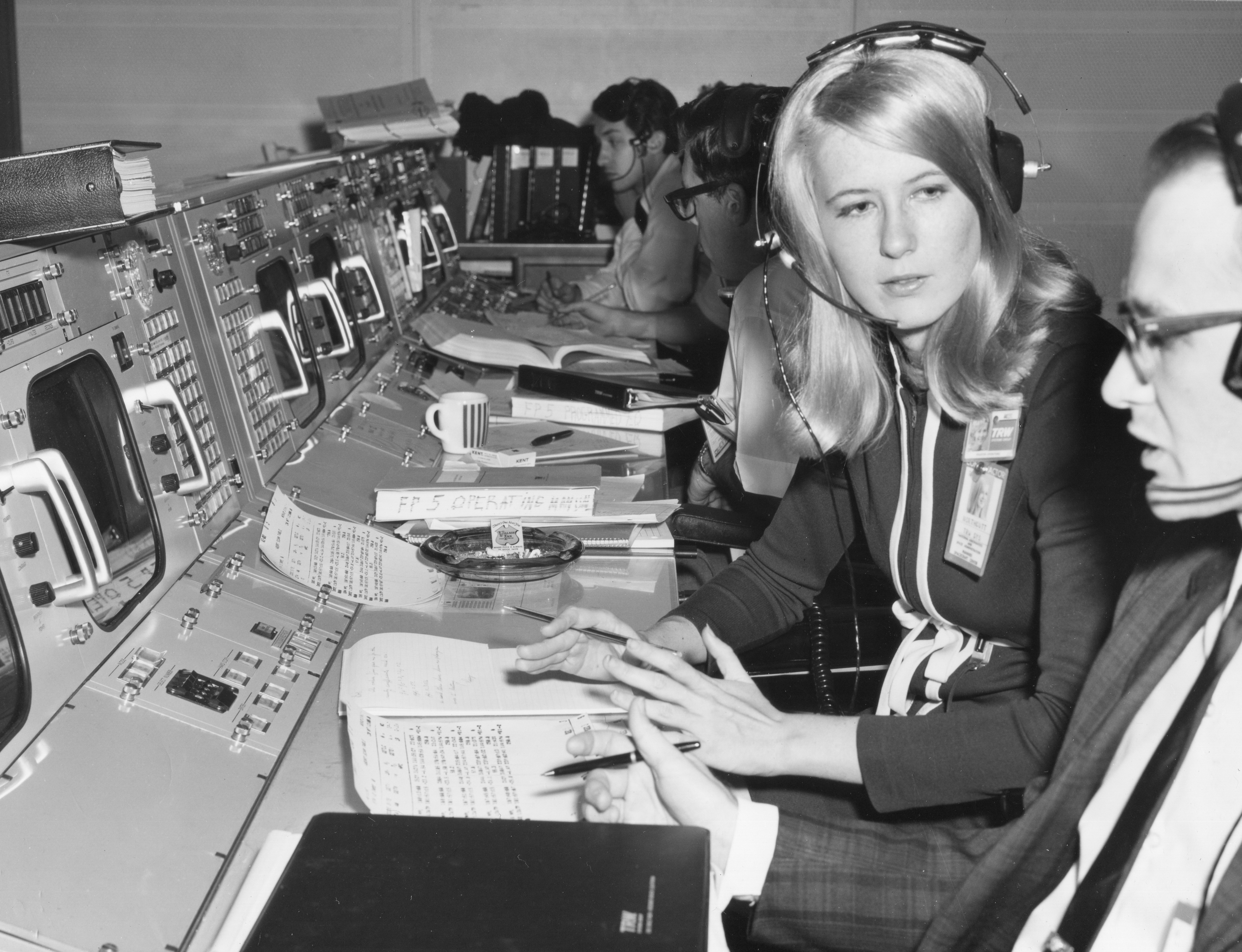

When Frances "Poppy" Northcutt says she wasn't supposed to be working on the Apollo 8 mission in December 1968, that had nothing to do with the fact that she was the only female working in NASA's famed Mission Control in Houston.

Rather, it was because Northcutt's expertise — helping astronauts during their trip home from the moon — was not initially needed for the mission, which was meant to remain in orbit around Earth. Her plans changed when NASA changed Apollo 8's destination to lunar orbit. The Americans heard rumors that the Soviet Union wanted to do its own human moonshot, and for international prestige, NASA wanted to get to that destination first.

Northcutt spoke with Space.com in conjunction with a documentary featuring her work, National Geographic Channel's "Apollo: Missions to the Moon," which aired July 7.

Related: Apollo 11 at 50: A Complete Guide to the Historic Moon Landing

After careful consultation with engineers, NASA management and the Apollo 8 crew, the three astronauts were approved for the journey of some 238,855 miles (384,400 kilometers). And Northcutt had a seat in the back room working on the crucial "trans-Earth injection" phase of the mission.

Northcutt recalled the tension in the room as the astronauts were turning on their engine for the ride home. "Those maneuvers are done on the back side of the moon, with no communication," she said. "It was the first time there had been a substantial period of time when the ground was not in communication with the spacecraft."

The maneuvers worked. As Apollo 8's Jim Lovell cheerfully announced that there was a Santa Claus, since the crew was safely on its way home in the early hours of Christmas morning, Northcutt's career moved into the front lines of history for two more years. Northcutt worked the back room for four more Apollo missions, including the first moon landing, part of Apollo 11, that took place 50 years ago on July 20.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

From computress to spacecraft navigator

Northcutt majored in mathematics in college, and when she came out of school, her first role was as a "computress" — "a gendered computer," she explains. She quickly ended up working at NASA's Langley Research Center where women worked behind the scenes plotting spacecraft trajectories.

The NASA astronauts rocketed to fame and the women doing the math were barely recognized for decades. Northcutt had a more philosophical take: "Apparently we women were considered good at number-crunching, and I suppose we were," she said.

Northcutt was a contractor at T.R.W. Systems, which is today (many mergers later) part of Northrop Grumman. Her specialty quickly got her promoted to working with the tricky math involved in bringing astronauts around the moon and safely home, where a spacecraft experiences lower gravity than in the more familiar environment at Earth. That changes aspects such as fuel usage and the timing of maneuvers, Northcutt said.

And that work eventually brought her into NASA's Mission Control between 1968 and 1970, working in a back room. Usually, two people worked at a time on trans-Earth injection, with shifts lasting 12 to 13 hours a day, she recalled. Generally, she would start work when a spacecraft was coasting toward the moon and preparing to enter lunar gravity, or "the moon's sphere of influence."

During lunar orbit insertion, Northcutt stood by just in case the crew had to abort and head back to Earth. She would remain at Mission Control during the lunar phase of the mission, which lasted a couple of days, reporting daily until the crew returned to the Earth's sphere of influence. Then, she would start getting ready for the next mission.

Northcutt worked Apollos 8, 10, 11, 12 and 13. Her most vivid memory of her work on Apollo 11 was how nominal the Earth-return process seemed during an otherwise historic mission: "Most of the time, I'm sitting there going, 'This is amazing. Everything is going right so far,'" she said.

"Particularly tense"

But that easy flight definitely wasn't the case for a later mission Northcutt worked, Apollo 13. That flight was nearing lunar gravity on April 13, 1970, when an explosion in the service module (which held oxygen and other supplies for the main command module spacecraft) changed the mission forever. With a crippled main engine on the command module, the normal plan to bring astronauts home was not an option. The three astronauts were low on oxygen, electricity and power and were forced to use their attached lunar lander as a lifeboat.

"[Apollo] 13, of course, was particularly tense," Northcutt recalled, but NASA did have a backup plan — using the lunar module's engine instead to rocket the astronauts back to Earth. "We had simulated doing returns to Earth using alternative space engines," she said, including the lunar module's descent engine, its ascent engine or a combination of the two. "So we were prepared to deal with the loss of that main spacecraft engine," she said.

The astronauts made it home safely, and missions were temporarily suspended as NASA made design changes to the spacecraft's service module, such as adding a third oxygen tank as a backup supply. Northcutt shifted to working on advanced missions, such as studying the fuel requirements for a crewed mission to Mars. Then she was "loaned" to the Houston mayor's office as a women's advocate. By the time she came back, T.R.W. Systems had lost its contract at NASA and Northcutt was eager for new challenges.

So this former mission controller became a lawyer, specializing in criminal law and eventually rising to be the first prosecutor in the domestic violence unit at the district attorney's office in Harris County, which includes Houston. From there, she went into private practice.

"I've always been a women's rights activist," she said, particularly focusing on reproductive rights. One of Northcutt's favorite career moments was helping to pass the Texas Equal Rights Amendment in 1972, which decreed equality under the law regardless of gender, skin color, race, national origin or religious identity.

Northcutt continues working part time on legal cases at an age when many would consider retiring. She said the space program helps her legal career in at least one way: She is well-practiced at "evaluating the reasonableness of technical evidence."

- Catch These Events Celebrating Apollo 11 Moon Landing's 50th Anniversary

- NASA's Historic Apollo 11 Moon Landing in Pictures

- Reading Apollo 11: The Best New Books About the US Moon Landings

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.