Glow of Alien Planets Detected in 'Milestone' Observations

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The glow of planets outside our solar system have been spotted in the first direct detections of light emitted by alien worlds.

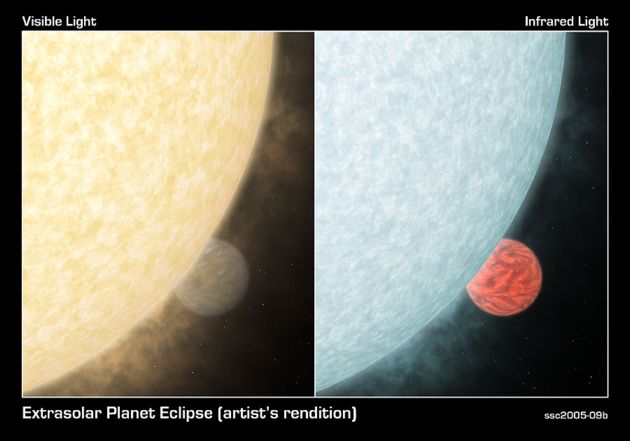

The two planets were detected in infrared light, an emission of heat that is not visible to the human eye. There are no conventional photographs, but astronomers are ecstatic nonetheless.

The gas giant worlds, each around a different star, were discovered previously by indirect methods. Both are roughly Jupiter-sized and hot, orbiting very close to their stars. Each completes a "year" in less than four days.

The observations, called a milestone by one analyst, were a surprising and serendipitous convergence of work by two separate teams.

"It's an awesome experience to realize we are seeing the glow of distant worlds," said David Charbonneau, a researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) who led the investigation of TrES-1, a planet a bit less massive than Jupiter that was found last year with the help of a backyard telescope.

Close scrutiny

The new technique, using NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, allows astronomers to probe the temperatures, atmospheres and emissions of planets, Charbonneau told SPACE.com. It might even let them measure wind for the first time on a planet around another star.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

TrES-1 and its star are about 500 light-years from Earth.

The other planet, named HD 209458b, is slightly lass massive than Jupiter and a bit larger. It is about 150 light-years from Earth. These observations were led by Drake Deming of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

In each system, the planet is in a direct line of sight in relation to the star, so that the planet moves across the star and then is eclipsed as it orbits around the star's back side. By comparing the total infrared emission from the reduced amount when the planet is eclipsed, Spitzer revealed the planet's exact emissions.

Using a variant of this "transit" method, astronomers have previously measured the visible light of a star, then noted how much it dimmed when a planet crossed in front. That provides an indirect measure of the planet's size but does not record light coming from the planet itself.

'Major milestone'

Alan Boss, a planet-formation theorist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, said directly detecting extrasolar worlds is one of the most significant moments in planet hunting since the first extrasolar worlds were discovered a decade ago. Boss, who was not involved in the new work, said 1995 and 2005 will be remembered as historical years in the ongoing search for planets like our own.

"It really is a major milestone," Boss said in a telephone interview.

Each planet was probed with a different Spitzer instrument recording different wavelengths of infrared light. Charbonneau and Deming knew of each other's projects, but their competitive natures kept them from discussing their progress.

"We had no idea where they were at," Charbonneau said.

After Charbonneau submitted his group's paper for publication, he notified NASA. He then learned of a remarkable coincidence.

"We had submitted the papers on the same day, not having known about each others' results," Charbonneau said. He and Deming then exchanged papers and met later to discuss their similar findings. They were amazed that they'd accomplished the same long-sought task using different instruments.

The discoveries were to be presented at a NASA press conference Tuesday afternoon. The HD 209458b study is discussed in a paper to be published online Wednesday by the journal Nature, according to NASA. The TrES-1 finding will be detailed June 20 in the Astrophysical Journal.

From the new detection, astronomers learned both planets are at least 1340 Fahrenheit (727 degrees Celsius) and have circular orbits.

That reopens a mystery.

Previous observations had found HD 209458b to have a very puffed-up atmosphere, which astronomers thought might have been caused by the tug of another, unseen planet. Were there another planet, then the orbit of HD 209458b would be noticeably non-circular.

"We're back to square one," said Sara Seager, a Carnegie Institution researcher involved in Deming's study. "For us theorists, that's fun."

First photo?

HD 209458b is arguably the most well studied extrasolar planet. Previous work by Charbonneau and others revealed oxygen and other gases in its atmosphere. It is so hot and close to its star that it is rapidly losing its atmosphere, according to another study.

Astronomers are still waiting for the first definite image of an extrasolar planet. The pictures may already have been taken, of a world orbiting a failed star known as a brown dwarf.

Those observations, by the European Southern Observatory and the Hubble Space Telescope, await confirmation. And the planet, if it is one, is unusually massive, with perhaps five times the heft of Jupiter. Imaging it -- as a point of light -- was possible because brown dwarfs do not create the overwhelming glare of a normal star.

The infrared-emitting planets discussed Wednesday are in many ways more interesting to astronomers because of their Jupiter-like dimensions and the fact that they orbit full-blown regular stars not unlike our Sun. And there's no doubt they are planets.

"Now we have our first genuine detection of light from a planet around a solar-like star," Boss said.

Next steps

Five other planets are known to transit in front of normal stars. But they are all too far away to be probed by Spitzer, which is operated by Caltech and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. A handful of other targets for Spitzer are likely to be found in coming years.

Meanwhile, more might be learned about HD 209458b and TrES-1. Each is thought to rotate in synch with its orbit, so that it always shows the same face to the star. That creates a tremendous heat imbalance between the two sides of the planet.

"It may also be possible to measure winds on these planets," Deming told SPACE.com. "This asymmetric heating should drive strong winds which attempt to redistribute the heat."

There are currently about 140 known worlds beyond our solar system. The first true photographs of extrasolar planets around normal stars are not expected for a few years, until NASA flies a new telescope devoted to the task.

- Youngest Planet

- Oldest Planet

- Hottest Planet

- Farthest Planet

- Earth-Like Planet

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.