First Invisible Galaxy Discovered in Cosmology Breakthrough

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronomers have discovered an invisible galaxy that could be the first of many that will help unravel one of the universe's greatest mysteries.

The object appears to be made mostly of "dark matter," material of an unknown nature that can't be seen.

Theorists have long said most of the universe is made of dark matter. Its presence is required to explain the extra gravitational force that is observed to hold regular galaxies together and that also binds large clusters of galaxies.

Theorists also believe knots of dark matter were integral to the formation of the first stars and galaxies. In the early universe, dark matter condensed like water droplets on a spider web, the thinking goes. Regular matter -- mostly hydrogen gas -- was gravitationally attracted to a dark matter knot, and when the density became great enough, a star would form, marking the birth of a galaxy.

The theory suggests that pockets of pure dark matter ought to remain sprinkled across the cosmos. In 2001, a team led by Neil Trentham of the University of Cambridge predicted the presence of entire dark galaxies.

One of perhaps many

The newfound dark galaxy was detected with radio telescopes. Similar objects could be very common or very rare, said Robert Minchin of Cardiff University in the UK.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"If they are the missing dark matter halos predicted by galaxy formation simulations but not found in optical surveys, then there could be more dark galaxies than ordinary ones," Minchin told SPACE.com.

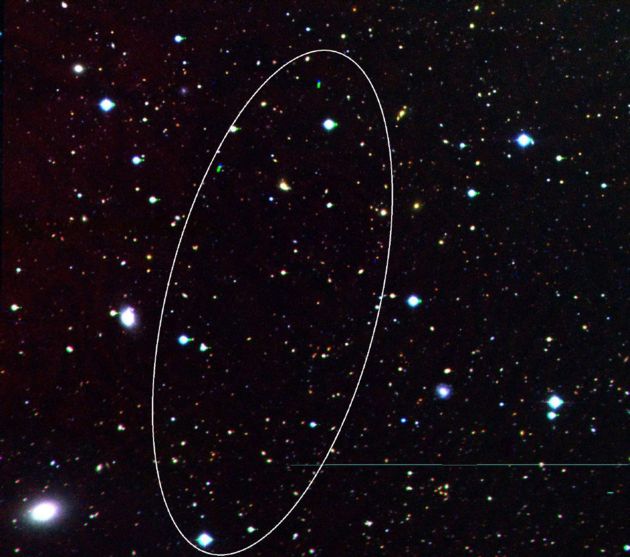

In a cluster of galaxies known as Virgo, some 50 million light-years away, Minchin and colleagues looked for radio-wavelength radiation coming from hydrogen gas. They found a well of it that contains a hundred million times the mass of the Sun. It is now named VIRGOHI21.

The well of material rotates too quickly to be explained by the observed amount of gas. Something else must serve as gravitational glue.

"From the speed it is spinning, we realized that VIRGOHI21 was a thousand times more massive than could be accounted for by the observed hydrogen atoms alone," Minchin said. "If it were an ordinary galaxy, then it should be quite bright and would be visible with a good amateur telescope."

The ratio of dark matter to regular matter is at least 500-to-1, which is higher than I would expect in an ordinary galaxy," Minchin said. "However, it is very hard to know what to expect with such a unique object -- it may be that high ratios like this are necessary to keep the gas from collapsing to form stars."

Long road to discovery

Other potential dark galaxies have been found previously, but closer observations revealed stars in the mix. Intense visible-light observations reveal no stars in VIRGOHI21.

The invisible galaxy is thought to lack stars because its density is not high enough to trigger star birth, the astronomers said.

The discovery was made in 2000 with the University of Manchester's Lovell Telescope, and the astronomers have worked since then to verify the work. It was announced today.

Additional radio observations were made with the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. Follow-up optical work was done with the Isaac Newton Telescope in La Palma. Astronomers from the UK, France, Italy and Australia contributed to the research. The project is now searching for other possible dark galaxies.

Dark matter makes up about 23 percent of the universe's mass-energy budget. Normal matter, the stuff of stars, planets and people, contributes just 4 percent. The rest of the universe is driven by an even more mysterious thing called dark energy.

- Prediction of Dark Galaxies in 2001

- About Dark Matter

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.