Surprising New View of Early Universe

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

New observations revealthat the early universe had its own version of rock-and-roll stars - galaxiesthat grew fast and died young. What killed these up-and-comers is not yetknown.

Using the Spitzer SpaceTelescope, Ivo Labbe of Carnegie Observatories and his colleagues studied abouta dozen massive galaxies shining two billion years after the Big Bang - whenthe universe was less than a fifth of its present age.

The galaxies, whichtypically had about 100 billion stars, constitute a variety of different types:some forming new stars, some clouded by dust, and some quite dead in terms oftheir ability to make new stars.

"It's becoming moreand more clear that the young universe was a big zoo with animals of allsorts," said Labbe, lead author of the study. "There's as much variety in theearly universe as we see around us today."

The most surprising ofthese animals are the dead galaxies that literally ran out of gas - or at leastcold gas - for making new stars. These giants suffocated far sooner than expected.

"We are really amazed- these are the earliest, oldest galaxies found to date," Labbe said."Their existence was not predicted by theory and it pushes back theformation epoch of some of the most massive galaxies we see today."

There are observations of even earlier galaxies - from less than a billion yearsafter the Big Bang, but the data are not good enough to tell what exactly wasgoing on inside them, said co-author Jiasheng Huang of the Harvard-SmithsonianCenter for Astrophysics.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Color-coding

Astronomers can tell the"liveliness" of a galaxy by its color. Galaxies with ongoing starformation are bluer because of the hot massive stars that shine the brightest.Older galaxies appear redder because massive stars burn out first - leavingonly the smaller, cooler stars.

"The current theorywould say that most [early] galaxies would be blue," Huang told Space.comin a telephone interview.

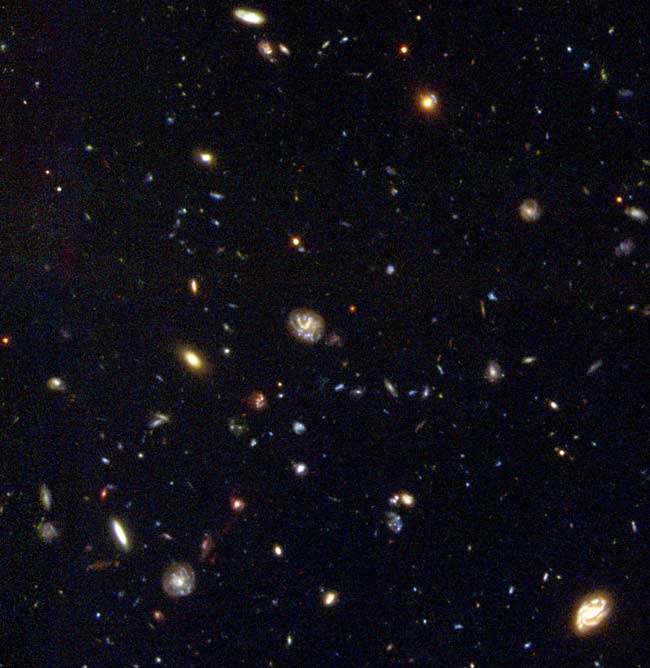

This is why Huang and his colleagueswere interested in looking at red galaxies seen in the Hubble Deep Field South- one of the space telescope's penetrating views into the early universe.

Besides early retirement,these Hubble-detected galaxies could appear red because they are full of dust,which absorbs blue light more than red. With Spitzer's infrared camera, Labbeand his team determined that 75 percent of the red galaxies were indeed dusty.

The rest, though, hadstopped forming new stars for about a billion years. Labbe said that it is rarefor galaxies to go that long without any star formation.

"Galaxies formstars," he said. "That is what they do."

Galaxy killers

According to Labbe, no oneis certain how these early galaxies petered out. They could be so massive thatthe gas inside became too hot to collapse into new stars. But this galaxy deathis thought to happen when the universe is much older.

Labbe thinks a moreplausible mechanism is that a super-massive black hole in the center of thesedead galaxies is swallowing up gas and spewing out jets and radiation in a waythat disrupts star formation in the rest of the galaxy.

Such violent super-massiveblack holes are typically seen as bright quasars, or more generally activegalactic nuclei (AGN). The astronomers plan in future observations to look forevidence of AGN in their dead galaxies.

Dead but not gone

Just because these earlygalaxies are "deceased," it does not mean they disappeared. Theirsmall red stars continued to shine for billions of years. In fact, some of thegalaxies around us today must have long ago looked dead. But which ones?

If you started with one ofthe galaxies seen in this study, and then ran the clock forward 12 billionyears to the present day, the galaxy would be more massive and look "evenmore dead," Huang said. Nowadays, the big and very red (dead) galaxies arethe giant ellipticals.

"It is very likelythat these dead galaxies evolve into massive giant ellipticals," Labbesaid.

But there are more giantellipticals than there were dead galaxies, so multiple avenues must exist formaking giant ellipticals, Labbe explained.

This article is part ofSPACE.com's weekly Mystery Monday series.

Michael Schirber is a freelance writer based in Lyons, France who began writing for Space.com and Live Science in 2004 . He's covered a wide range of topics for Space.com and Live Science, from the origin of life to the physics of NASCAR driving. He also authored a long series of articles about environmental technology. Michael earned a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Ohio State University while studying quasars and the ultraviolet background. Over the years, Michael has also written for Science, Physics World, and New Scientist, most recently as a corresponding editor for Physics.