Hubble Confirms Young Planet at Nearby Star

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

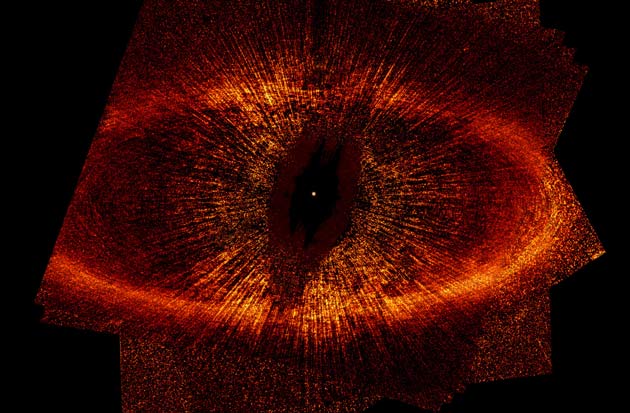

New observations of a star suspected of harboring a planet provide the most convincing evidence yet of the young world's existence.

Rather than spotting the planet, however, astronomers have photographed an odd-shaped ring of dust that surrounds the star. They assume that the unseen planet sculpted the arrangement.

The star, Fomalhaut, is the 17th brightest in our night sky and is easily found with the unaided eye and a sky chart. It is a relatively young star, still shrouded in the dust of its birth.

Fomalhaut is about 25 light-years away.

Distortions explained

In 2002, astronomers said they had found distortions in Fomalhaut's disk-like dust ring and calculated that a Saturn-sized planet must be orbiting the star. Observations also hinted that the ring was offset in relation to the star a manner that suggested the presence of a planet, but that speculation was based partly on computer models.

The new optical view, from the Hubble Space Telescope, reveals the exact dimensions of the swirling mass of star-formation leftovers.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The dust ring is not centered on star as would be expected if only the star's gravity had sculpted it. Instead, the center is 1.4 billion miles (15 times the distance from Earth to the Sun) away from the star. That is strong evidence of a planet tugging on the ring, scientists said today.

"Our new Hubble images confirm those earlier hypotheses that proposed a planet was perturbing the ring," said Paul Kalas of the University of California at Berkeley.

A familiar ring

Kalas and his colleagues assume the mystery object is a planet and not something larger, such as a dim failed star known as a brown dwarf, because they say Hubble would have spotted a brown dwarf directly with the observations that were made.

The investigation is important because the Fomalhaut (Fo-mal-ought) system is thought to resemble our own solar system when it was about 200 million years old (ours is now 4.6 billion years old). Astronomers have a theoretical model for how the planets formed, but only by looking at young solar systems can they confirm that the process played out as expected.

The ring around Fomalhaut resembles our solar system's Kuiper Belt, a region of comet-like objects beyond Neptune. Astronomers think that as planets, asteroids and comets develop out of dust, a lot of material is kicked either inward to the star our outward into a leftover ring of debris.

Importantly, the theory holds that the region near a newborn star, such as the location of Earth, is bereft of water in a solar system's early years. Some of icy material that develops farther out is, however, expected to be booted inward after planet formation, bringing precious water ice to nascent planets and providing the ingredients for life.

While confident that such a process set up conditions for biology on Earth, scientists are eager to learn if the scheme is common.

More evidence

Hubble provided more clues suggesting a planet.

The ring's inner edge is sharper than the outer edge, consistent with computer models of a planet sweeping material up in the manner of a snowplow. The width of the ring, now measured to be about 2.3 billion miles, is also what would be expected if it's shaped by a nascent world. With no planet to keep material in check, the ring would be wider.

The shepherding of the ring is similar to what is seen in the rings of Saturn, which are confined by the gravitational influence of moons, Kalas said.

Despite similarities to our solar system, the setup at Fomalhaut is also distinct.

"While Fomalhaut's ring is analogous to the Kuiper Belt, its diameter is four times greater than that of the Kuiper Belt," Kalas said. That suggests "that not all planetary systems form and evolve in the same way."

Indeed, many of the other 150 or so extrasolar planets found to date orbit incredibly close to their host stars. In some systems, Jupiter-sized worlds orbit a star in just a few days. Other planets take wildly eccentric paths around their stars.

The findings are detailed in the June 23 issue of the journal Nature.

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.