Strange New World Unlike Any Other

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

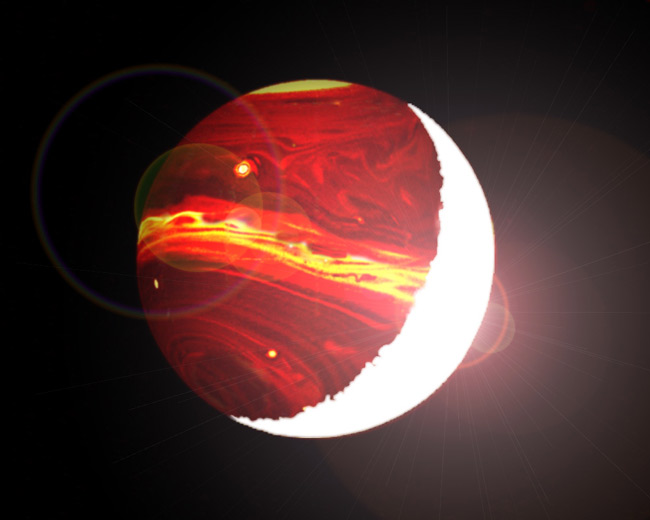

A strange newfound planet as massive as Saturn appears to have the largest solid core known, providing an important clue to how some giant planets might form and setting off a controversy over how it formed.

The world passes in front of its host star, so even though they can't actually see the it, astronomers were able to glean important information about its size and density, and therefore infer things about its composition.

Scientists who investigated the large and presumed rocky core of the planet say it supports the idea that giant planets can indeed form by gradual accumulation of a core, long the leading theory of planet formation but one that has been called into question lately.

But how it grew such a massive core is beyond the ability of current theories to explain, according to one expert who does not agree that the isolated discovery proves anything.

Standard model

With the standard core accretion model, as it is called, dust around a newborn star gathers into clumps, which become asteroids, comets and protoplanets. Some grow large enough to form rocky worlds like Earth. The theory states that a giant planet like Jupiter is created in the same manner, reaching a critical point when its core is massive enough to attract a large envelope of gas.

But the giant planets in our solar system don't have cores large enough to prove the idea. Other researchers have suggested that they might have formed, instead, by the sudden collapse of gas from a knot in the cloud of material that circles a new star.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"For theorists, the discovery of a planet with such a large core is as important as the discovery of the first extrasolar planet around the star 51 Pegasus in 1995," said Shigeru Ida, theorist from the Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan.

The planet orbits a sun-like star called HD 149026.

It is very close to the star, taking just 2.87 days to make a yearly orbit. That makes it hot -- about 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit on the star-facing side. Modeling of the planet's structure shows it has a solid core approximately 70 times Earth's mass.

The scientists don't believe the core could have formed by cloud collapse. They think it must have grown by accumulation of dust and rock, and then acquired gas.

The finding does not rule out collapse as an alternate means of making planets. Astronomers don't know if there are multiple methods or not.

"This is a confirmation of the core accretion theory for planet formation and evidence that planets of this kind should exist in abundance," said Greg Henry, an astronomer at Tennessee State University, Nashville. Henry detected the dimming of the star by the planet with robotic telescopes at Fairborn Observatory in Mount Hopkins, Arizona.

Not so fast

Not so fast, says Alan Boss, a theorist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington who has championed the collapse model in recent years.

"I have not seen any core accretion models that predict the formation of such a beast," Boss told SPACE.com. "I suspect that the core accretion folks will be scratching their heads for a while

over how this thing could have formed."

Since this planet is just one of about 150 that have been discovered beyond our solar system, Boss thinks its premature to claim core accretion has been proved.

"I suspect that both disk instability and core accretion can occur, as well as intermediate, hybrid mechanisms," Boss said.

The research was supported by NASA, the National Science Foundation and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan. The discovery will be detailed in the Astrophysical Journal.

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.