Space Telescope Sees 'Mountains of Creation'

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

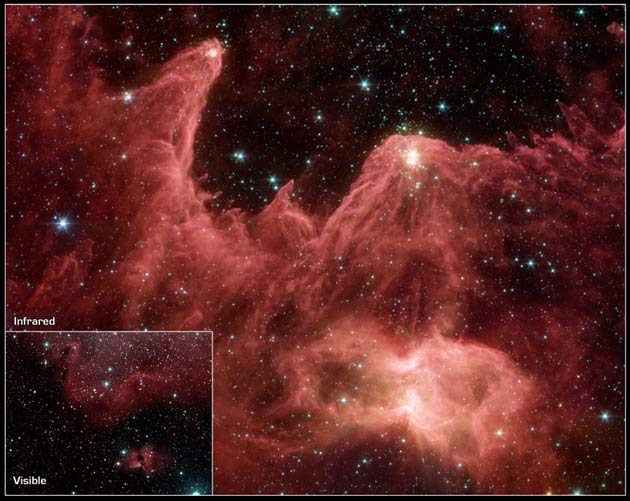

Giant clouds of gas and dust harboring embryonic stars rise majestically into space in a new picture from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope.

The image, dubbed the Mountains of Creation by astronomers, reveals hotbeds of star formation similar to the iconic Pillars of Creation within the Eagle Nebula, photographed in 1995 by the Hubble Space Telescope. In both cases, the finger-like features are cool clouds of gas and dust that have been sculpted by radiation and fast-moving winds of charged particles from hot, massive stars.

Spitzer records heat, or infrared light, which penetrates the dusty clouds and allows a view of the star birth inside. In the largest finger, hundreds of embryonic stars not seen before are revealed. Dozens of stars-to-be are visible in one of the other fingers.

The Spitzer image shows the eastern edge of a region known as W5, in the Cassiopeia constellation 7,000 light-years away. A massive star outside the frame lights the scene.

The pillars are are more than 10 times the size of those in the Eagle Nebula.

Over the past decade, thanks in large part to the 1995 Hubble image and subsequent investigations of the Eagle Nebula and similar stellar cradles, astronomers have learned that intense outflows from massive stars actually help birth more stars. Such appears to be the case in the new Spitzer image.

"We believe that the star clusters lighting up the tips of the pillars are essentially the offspring of the region's single, massive star," said Lori Allen, lead investigator of the new observations from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. "It appears that radiation and winds from the massive star triggered new stars to form."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Visible-light images of this same region show dark towers outlined by halos of light. They are not as dramatic because the clouds block the light coming from the embryonic stars.

The researchers think W5 started out as thick and turbulent clouds of gas and dust. Stars, some more than 10 times the mass of the Sun, were born in groups. Then radiation and winds from these massive stars forced material outward, leaving the dense pillar-shaped clumps.

Many astronomers think our Sun was formed in a similar setup, then later migrated away from the clump.

The Spitzer picture also reveals blue stars, which are older and sit in cavities within the clouds. They are thought to have been born around the same time as the massive star outside the frame that was responsible for the whole scene.

"With Spitzer, we can not only see the stars in the pillars, but we can estimate their ages and study how they formed," said Joseph Hora, also from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

- Hubble's New Views of the Universe

- New Look at Fate of the Pillars of Creation

- Origins Revealed: Sun and Earth Born amid Chaos

- Violent Young Stars Hint at Earth's Wild Start

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.