Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Washington, DC-Light from the North Star, Polaris, has helped humans find their way for thousands of years. Yet its gravity has guided the movements of two lesser known companion stars for much longer.

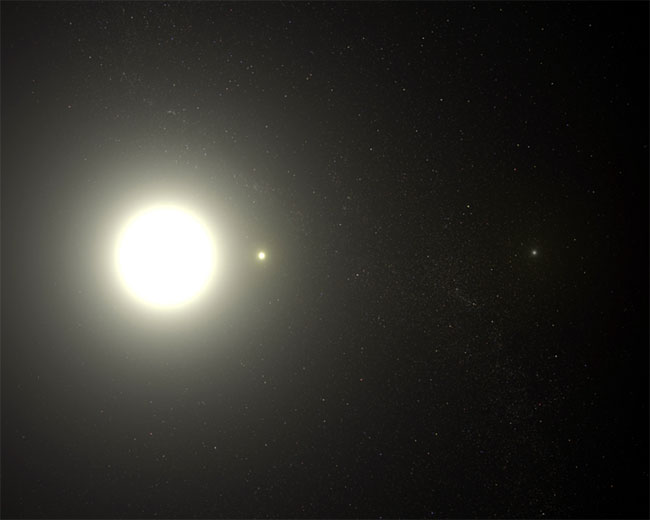

One of its stellar companions is clearly visible with a telescope, but the other hugs Polaris so tightly that it has never been directly observed until now. Using the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers have photographed this close neighbor for the first time, recording its ultraviolet light.

"The star we observed is so close to Polaris that we needed every available bit of Hubble's resolution to see it," said Nancy Evans, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who participated in the research.

Article continues belowThe newly observed companion star is about 2 billion miles from Polaris. Astronomers have known about it for about 50 years from analysis of light coming from the triple star system, but it was so dim compared to Polaris that direct observation was impossible.

Better estimates

The observations have helped researchers refine mass estimate for the main star and the newly photographed companion.

"The companion is a little more massive than the Sun and a little brighter and a little hotter," Evans said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Early estimates suggest that Polaris is about four times more massive than the Sun, but the researchers hope to refine their estimate with observations about the companion star's orbit.

The research was presented here today in a press conference at the 207th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

Out of the shadows

"With Hubble, we've pulled the North Star's companion out of the shadows and into the spotlight," said astronomer Howard Bond from the Space Telescope Science Institute, which operates Hubble for NASA and the European Space Agency.

Polaris is the brightest star in the constellation Ursa Minor and located about 431 light-years away. It is situated almost directly above the celestial north pole, making it Earth's current northern polestar. It appears as a fixed point in the night sky around which all the other stars revolve, and sailors have long used it to orient themselves.

Polaris belongs to a special class of massive, pulsating stars known as Cepheids, which dim and brighten at regular intervals. Scientists use Cepheids to measure the distance to faraway galaxies and star clusters and to calculate the expansion rate of the universe. Knowing a Cepheid's mass is important to this understanding, but calculating the mass for most stars is difficult.

Although Polaris is a triple star system, it can be broken down into a binary system and a single star located farther away. Binary systems are important because their stars are among the few whose masses can be accurately determined. But calculating the mass for each star in a binary setup requires knowledge of their complete orbits. This in turn requires visual observation of their movements-something that was impossible with the Polaris binary system until now.

"Our ultimate goal is to get an accurate mass for Polaris," Evans said. "To do that, the next milestone is to measure the motion of the companion in its orbit."

- Triple Star Systems are Common

- Detailed Measures Taken of Closest Star System, Alpha Centauri

- Massive North Star Polaris Surprises Scientists at the Naval Observatory With Its Size

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.