WASHINGTON, D.C.-Scientists have found the first strong evidence that supermassive black holes at the hearts of some galaxies weren't born big, but grew to their monstrous sizes through the mergers of smaller galaxies.

In the process, the researchers also revealed two distinct phases of galaxy evolution, including an early "tadpole" phase in which two galaxies merge.

"Black hole growth and galaxy mergers had been long suspected but we now have a bit of a smoking gun," said Rogier Windhorst, an astronomer at the Arizona State University who lead the study.

Two teams presented results of the study here today at the 207th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

Broad implications

The findings also confirm the predictions of recent computer simulations of a team of researchers from the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics that newly merging galaxies kick up so much dust that astronomers can't see into their centers where the supermassive black holes reside.

The simulations suggested that hundreds of millions of years may pass before the dust clears up enough to allow a good look at the region near a central black hole.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

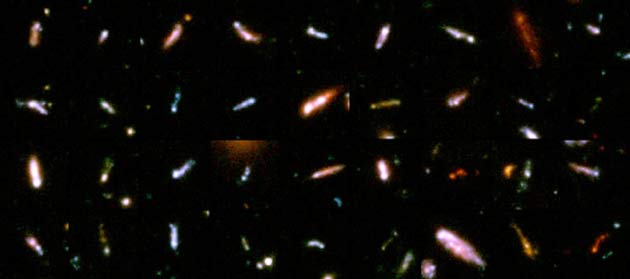

Using the Hubble Ultra Deep Field (HUDF), the astronomers searched through thousands of galaxies and found 165 so-called tadpole galaxies that are thought to represent the early phases of two merging galaxies. The galaxies are so named because they have a shape consisting of a bright, dense knot of stars and a faint, trailing tail made up of trailing stars that managed to escape the galaxies' gravitational pull.

It's believed that when two galaxies first come together to form the distinctive tadpole shape, they stir up so much dust that their central black holes become hidden.

More learned

The researchers also detected a second class of galaxies which they believe represent a later phase of galaxy evolution, one that takes place millions of years after the tadpole stage. In this phase, called the "variable-object phase," the dust that once enshrouded the merging black holes has cleared away and the immediate vicinity of the much larger black hole becomes visible and begins emitting a flickering light, which astronomers can detect.

The light is believed to be caused by material swirling into the black hole. As the material is heated, it begins to glow and can rapidly change in brightness.

It was once thought that tadpole galaxies should also emit this varying light because as their two galaxies merged, their black holes were merging as well.

"Once the whole galaxy settles, the black holes will find each other in the gravitational center," Windhorst said. "It's like having two huge marbles and throwing both in the pool-they will both roll into the center of the pool."

When the researchers looked for this light in the tadpole galaxies, however, they could not find any.

This absence of light supports a recent computer model that suggests that astronomers will not be able to detect the light coming from the black holes of the merged galaxies until hundreds of millions to billions of years after the merger, due to the thick veil of dust that surrounds the entire system.

- The New History of Black Holes: 'Co-evolution' Dramatically Alters Dark Reputation

- Studies Show Black Holes Formed Quickly After Big Bang

- Monster Black Holes: How Galactic Collisions Fed Them

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.