The Origins Of The Man In The Moon

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

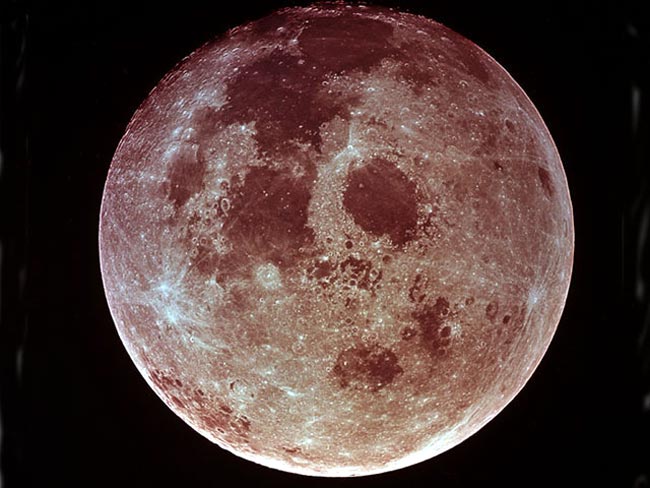

The "Man in the Moon" illusion, familiar to various cultures around the world, was created by powerful asteroid impacts that rocked the satellite billions of years ago, a new study suggests.

The study, performed by Laramie Potts and Ralph von Frese of Ohio State University, reveals that ancient lunar impacts played a much larger role in shaping the Moon's surface than scientists had previously thought. It may also help explain the origins of two mysterious bulges on the Moon's surface.

The new analysis reveal that shock waves from some of the Moon's early asteroid impacts traveled through the lunar interior, triggering volcanic eruptions on the Moon's opposite side. Molten magma spewed out from the deep interior and flooded the lunar landscape.

When the magma cooled, it created dark patches on the Moon called "lunar maria" or "lunar seas."

During a full Moon, some of these patches combine to form what looks like a grinning human face, commonly known as the "Man in the Moon." The man's eyes are the Mare Imbrium and Mare Serenitatis, its nose is the Sinus Aestuum and its grinning mouth is the Mare Nubium and Mare Cognitum.

The effects of some of those traveling shock waves are still visible in the Moon's interior today. Cross-sectional images of the insides reveal that a part of the mantle, the section between the Moon's core and crust, still juts into its core today, 700 miles below the point of one of the impacts. The images were created from data collected by NASA's Clementine and Lunar Prospector satellites.

Mysterious bulges

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Early surveys by the Apollo missions revealed that the moon isn't a perfect sphere. There is a bulge on the Earth-facing side, called the near side, and another bulge on the far side.

According to one hypothesis, these bulges are the result of Earth's gravity tugging on the Moon during the early years following its cataclysmic formation, when its surface was still molten and malleable.

The current study suggests that this scenario is only partly correct. The researchers think the Moon was struck by at least two very powerful asteroid impacts in its past (in addition to countless smaller impacts that left smaller craters easily identifiable still today). One of the major impacts struck the near side, sending shock waves that traveled through the lunar interior to create the bulge on the far side; the other impact struck the far side and created the bulge on the side.

The researchers think the impacts happened about four billion years ago. At that time, roughly half a billion years after the birth of the solar system, the Moon was still geologically active and its core and mantle were still molten and malleable.

Back then, the Moon was much closer to the Earth than it is today and the gravitational interactions between the two were much stronger. The researchers think that when magma spilled out of the Moon's interior, Earth's gravity immediately grabbed hold and hasn't let go since.

"This research shows that even after the collisions happened, the Earth had a profound effect on the Moon," Potts said.

The findings were detailed in a recent issue of the journal Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors.

- Skywatcher's Guide to the Moon

- Lunar Prospector Data to Yield New Moon Maps

- 24 Hours of Chaos: The Day The Moon Was Made

- Moon Mechanics: What Really Makes Our World Go 'Round

- Top 10 Cool Moon Facts

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.