Gas Blob Resembles Gigantic Comet

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A ball of gas more massive than a billion suns is hurtling like an enormous comet through the interior of a distant galaxy cluster.

The massive structure is held together by mysterious dark matter, astronomers said today, but it is steadily breaking apart and becoming fuel for new stars.

"This is likely a massive building block being delivered to one of the largest assembly of galaxies we know," said study team member Alexis Finoguenov of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

The finding is detailed in the June 6 issue of Astrophysical Journal.

Great ball of fire

The gas blob is moving at nearly 500 miles (750 kilometers) per second relative to the galaxy cluster it is embedded within. Called Abell 3266, the cluster is itself moving away from us at a speed of nearly 11,000 miles (17,000 kilometers) per second.

Nicknamed "comet," the gas ball is the largest of its kind ever detected. It measures about three million light-years across, or around five billion times the size of our solar system. The gas is estimated to be about 84 million degrees Fahrenheit (about 46 million degrees Celsius). Although this might seem hot to us, it is still relatively cool compared to some interstellar gas.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The gas blob is thought to have formed when two galaxy clusters-one large and one small-collided billions of years ago. During the crash, a blob of relatively cool gas from the small cluster was sheared off and sent careening off into space on its own.

During its travels, it got sucked in by the immense gravity of galaxy cluster Abell 3266, which it entered some 2 billion years ago. The blob is currently near the center of Abell 3266.

Star fodder

Abell 3266 is one of the most massive galaxy clusters in the southern sky, containing hundreds of galaxies and large amounts of superheated gas. Scientists think that dark matter-a mysterious substance believed to make up the bulk of matter in the universe-is the invisible glue holding both Abell 3266 and the gas ball together.

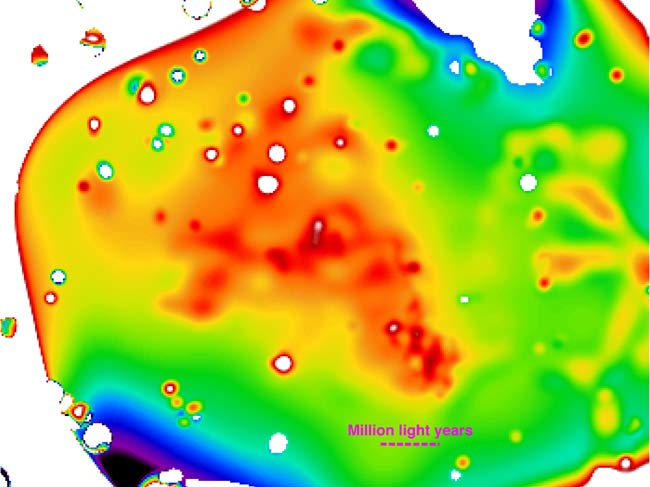

Using X-ray data from the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton satellite, the researchers produced an entropy map of Abell 3266 and the gas ball. In thermodynamics, entropy is a measure of the degree of randomness or disorder in a system.

The map shows gas being stripped from the gas comet's core and forming a large tail containing scattered clumps of cold, dense gas. The researchers estimate that about a sun's worth of mass is being lost by the gas comet every hour.

This stripped-off gas will likely become fuel for new stars, said study team-member Mark Henriksen, also of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

The gas comet is so massive that it could probably form it's own galaxy, but the researchers think the more likely scenario is that it'll add to the bulk of a giant elliptical galaxy already forming in the center of Abell 3266.

"It'll sort of collapse down to the center, and in a few billion years off it'll become stars in that galaxy," Henriksen told SPACE.com.

- VOTE: Most Amazing Galactic Images

- How a Star is Born: Clouds Lift on Missing Link

- Collapse or Collision: The Big Question in Star Formation

- Maturity of Farthest Galaxy Cluster Surprises Astronomers

- Ongoing Growth: Galaxies Grab Intergalactic Gas

- Nebulas: The Best of Your Amazing Images

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.