The History of Dark Energy Goes Way, Way Back

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

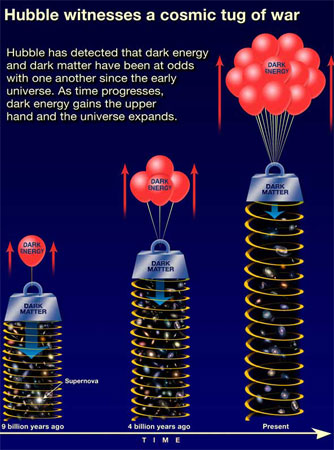

Scientists now have evidence that dark energy has been around for most of the universe's history.

Using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, researchers measured the expansion of the universe 9 billion years ago based on 23 of the most distant supernovae ever detected.

As theoretically expected, they found that the mysterious antigravity force, apparently pushing galaxies outward at an accelerating pace, was acting on the ancient universe much like the present.

All supernovas of a certain variety, called Type-1a, burn with the same brightness, so scientists can calculate relative distances in the universe based on how dim or bright these exploding stars get. In the late 1990's it was realized that these standard candles were dimmer than expected and that the expansion of the universe was accelerating.

Scientists blamed the acceleration on an inexplicable repulsive force, dark energy.

"Although dark energy accounts for more than 70 percent of the energy of the universe, we know very little about it, so each clue is precious," said Adam Riess, a professor at Johns Hopkins University who was involved in the initial discoveries back in the '90s. "Our latest clue is that the stuff we call dark energy was present as long as 9 billion years ago, when it was starting to make its presence felt."

The universe is about 13.7 billion years old.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers believe that although this new observation is a significant clue in the quest to understand what is probably, in Riess's words "one of the most, if not the most, pressing question in physics," it's far from the proof to what dark energy actually is.

Mario Livio from the Space Telescope Science Institute put the situation in perspective at a media teleconference at NASA headquarters today. "Water covers 70 percent of the surface of the Earth," Livio said, yet it took humans many centuries to first discover the properties of water. With dark energy, he said, researchers are still in the phase of determining its properties.

Previous observations revealed that the early universe was comprised of matter whose gravity was trying to pull it all inward and slow down its expansion. But the spreading out of the cosmos started speeding up around 5 billion to 6 billion years ago. That's when scientists believe dark energy started to win the cosmic tug of war.

"After we subtract the gravity from the known matter in the universe, we can see the dark energy pushing to get out," said Lou Strolger from the University of Western Kentucky.

Another important finding, the researchers said, is that they can now compare the properties of ancient stellar explosions to today's explosions.

"This is important because we use these tools to measure the universe [and] we need to make sure that our understanding of their nature themselves have not changed," Riess said. The chemical composition in these 9-billion-year-old supernovas look remarkably similar to those that occur in the modern universe. So this finding continues to validate the use of supernovas as cosmic probes for understanding the nature of dark energy.

This latest finding is consistent with Einstein's explanation for what dark energy is, the researchers noted. Einstein's "cosmological constant" idea, which he called his biggest blunder and later rejected, turned out to be the same thing that scientist now see as the repulsive form of gravity called dark energy.

The findings will be published in the Feb. 10 issue of Astrophysical Journal.

- Dark Energy Tied to Human Origins

- Nearby Evidence for Dark Energy

- Images: Hubble's New Views

- All About the Universe