Underground Plumbing System Discovered on Mars

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A Mars-orbiting spacecraft has spotted a subterranean natural plumbing system that might have ferried water beneath the surface of the red planet in the distant past.

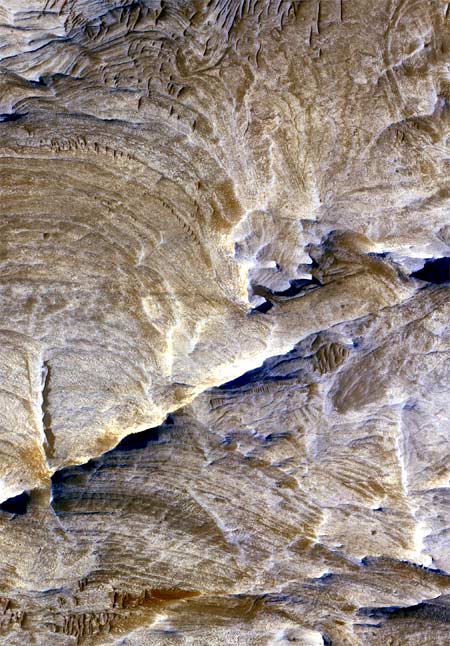

New images taken by the HiRISE camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) show hills and plateaus with alternating layers of dark and light colored rocks in Candor Chasma, one of several canyons that make up Valles Marineris, a sprawling Martian rift valley that is longer than the contiguous United States and up to seven times deeper than the Grand Canyon in places.

Cutting like a vertical scar across these light and dark bands in Candor Chasma are a series of linear cracks surrounded by "halos" of light-colored bedrock [image].

Pipes in bedrock

In the Feb. 16 issue of the journal Science, University of Arizona researchers Chris Okubo and Alfred McEwen argue that the halos are proof that some form of fluid-either water, liquid carbon dioxide or a combination of the two-once flowed through the bedrock.

The timing of the flow remains uncertain, the researchers say, and could have occurred many millions or even billions of years ago.

They suggest that liquid flowing through the fractures deposited iron-rich or clay-like minerals in the rock. The minerals would act like cement to strengthen the layers of rock and also bleach it a lighter color. Over millions of years, wind stripped away the top layers of surface rock, exposing the subsurface and its plumbing system to the light of day.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The linear cracks, called joints, are about a meter wide and range from several hundred meters to several kilometers in length. How the joints formed is still a mystery, but once formed, they would have provided a conduit for flowing liquid, the researchers speculate.

"They acted sort of like pipes through the bedrock," Okubo told SPACE.com.

- Video: Life on Mars?

Earth analogy

Similar processes are known to occur on Earth. Veins of gold and silver in rock, for example, are formed when water rich in the dissolved forms of these elements flows through cracks and finally deposit the metals as bright streaks in the rock.

Okubo says the new findings could have implications for life on Mars, either in the distant past and perhaps even the present.

By being underground, the "fluid can remain in place for a longer period of time," Okubo said. "That will allow for the geochemical reactions to occur more thoroughly and more profusely through the rock, perhaps giving rise to habitable oases within the protected subsurface for any biologic activity to occur."

Philip Christensen, a leading Mars researcher at Arizona State University, said the team's explanation for the joints is very plausible, but points out that the liquid that once flowed through the cracks might also have been volcanic magma.

Molten magma flows like liquid and can also alter the color of surrounding rocks, Christensen said. It looks as if "fluid was injected into these cracks. The question is what was the fluid? Was it water or was it volcanic?"

Christensen added, however, that there are no large volcanoes in the Candor Chasma region photographed by the MRO, so "water moving through those fractures is probably more likely than volcanic material."

- Image Gallery: Red Planet Revealed

- New Look at Mars Rock Layers Hint at Water

- Volcanic Activity Brought Mars Water to Surface

- Changing Mars Gullies Hint at Recent Flowing Water

- All About Mars

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.