Mystery of Red Space Glow Solved

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

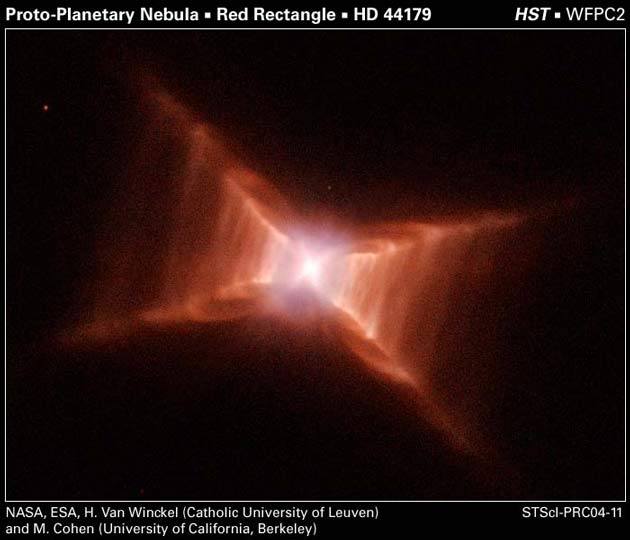

Scientists have solved a decades-long mystery of a red glow that permeates our Milky Way Galaxy and other galaxies.

The red glow is most prominent in a strange, dying star called the Red Rectangle, named for the bizarre structure that surrounds it.

The red light, astronomers now say, radiates from invisibly small clusters of dust that are now believed to glow because of newly described molecular forces that oppose each other on very small scales.

The glow, called the Extended Red Emission (conveniently ERE for short) has been known but inexplicable for more than 30 years. Researchers suspected carbon-rich molecules called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) were the culprit. These clusters of molecules form a structure that looks like chicken wire; they are measured on a scale of billionths of a meter, far too small to see.

Thing is, for PAHs to create the red glow, they would have to be bombarded by ultraviolet radiation so harsh that it would destroy all known forms of these structures.

"Although I had results that strongly supported the idea that PAHs had something to do with the ERE, the experimental results made it clear that if PAHs were involved, they were present in some as-yet unknown exotic form," said Murthy Gudipati, a NASA researcher also at the University of Maryland. So exotic, indeed, that they can't be recreated in a lab. In fact, the red glow seen in space doesn't occur on Earth because the nano-sized PAH clusters are very reactive and don't last long.

So Gudipati and colleagues, led by Louis Allamandola at NASA's Ames Research Center, employed some fancy theoretical chemistry calculations to the problem. The glow comes from unusual clusters of PAHs that are charged and highly reactive but, at the same time, "have a stable, closed-shell electron configuration as does any stable molecule on Earth," the researchers said in a statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Our simulation shows that this type of charged PAH cluster can account for the ERE while satisfying the physical requirements necessary to survive the harsh interstellar conditions," said team member Young Min Rhee, postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Berkeley.

The findings were detailed recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The research could help scientists better understand how soot is formed during combustion in diesel engines and jets, a process that's poorly understood. The PAHs might serve as seeds in a flame around which a soot particle forms, the scientists said.

- Top 10 Strangest Things in Space

- Mystery Ocean Glow Confirmed in Satellite Photos

- Top 10 Unexplained Phenomena

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.