Our solar system is hurtling through space while angled nearly perpendicular to the plane of the Milky Way, new computer models suggest.

"It's almost like we're sailing through the galaxy sideways," said study team leader Merav Opher, an astrophysicist at George Mason University in Virginia.

The findings, detailed in the May 11 issue of the journal Science, suggest the magnetic field in the galactic environment surrounding our solar system is pitched at a sharp angle and not oriented parallel to the plane of the Milky Way as previously thought.

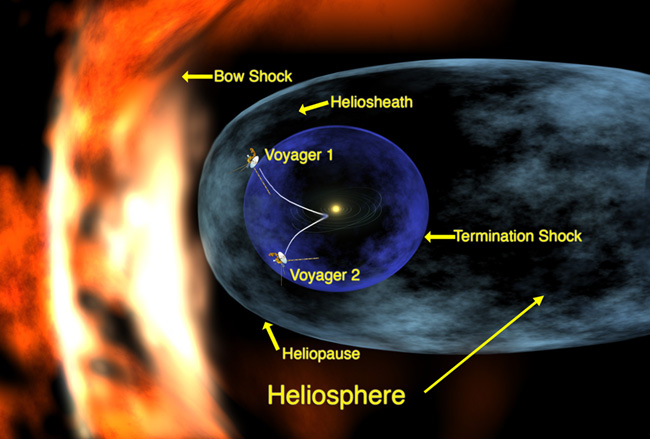

The heliosphere

The clue to the angle was found in the charged cocoon-like shroud around the solar system, called the heliosphere and comprised of the Sun's solar wind, the stream of charged, low-energy particles it emits. As our Sun and its planets travel through space, interstellar gases press against the heliosphere, stretching this steady cosmic gale lengthwise into a bullet shape that stretches far past Pluto.

Data recently received from the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft reveal the heliosphere's shape is deformed in another way: the northern hemisphere bulges outward while the southern hemisphere is pressed inward.

Using computer simulations, Opher and her team concluded that this asymmetry is best explained if the local galactic magnetic field, located just outside our solar system, is angled some 60 to 90 degrees to the plane of the Milky Way.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The galactic magnetic field influences the orientation of the solar system's heliosphere, causing it to incline at a sharp angle, Opher said. An analogy is a bullet hurtling through the air with its nose turned toward the ground.

"If you assume that you have a magnetic field in the plane of the galaxy, you get the wrong distortion," Opher told SPACE.com.

The new study is the first to look at the local galactic magnetic field, Opher said. Previous research involved measuring the galactic field over massive distances, more than a thousand times the scale of the heliosphere.

"It's like instead of measuring continents, you're measuring countries," Opher said.

Turbulence

The source of our galaxy's magnetic field is a mystery. The most accepted idea, Opher said, is that the large cloud of interstellar dust and gas from which our galaxy formed had a magnetic field, and that the field got squished when the cloud collapsed into a disk to form the Milky Way.

"But you can also ask 'What formed the magnetic field of this cloud?'" Opher said.

Randy Jokipii, an astrophysicist at the University of Arizona who was not involved in the new study, suggests in an accompanying Science article that the findings of Opher's team can be explained if the galactic magnetic field is thought of as a turbulent fluid. Turbulence is a phenomenon whereby a fluid breaks down randomly into eddies and no longer flows smoothly, like creamer poured into a cup of coffee.

Opher says the idea of a turbulent galactic magnetic field is not new to scientists. "We've thought about it, but [our findings] indicate it might really exist," she said.

- Behind the Pictures: Top 10 Voyager Facts

- The New Tourist's Guide to the Milky Way

- Voyager 2 Detects Odd Shape of Solar System's Edge

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.