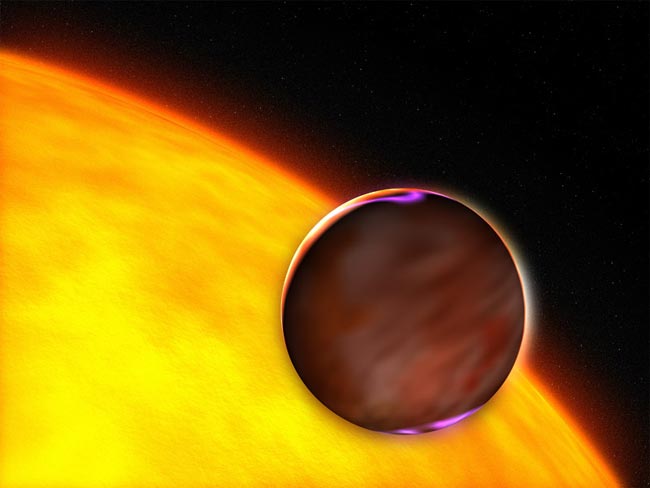

A Neptune-sized world in a distant solar system orbits very close to its star and might be covered with exotic forms of water not naturally found on Earth, scientists say.

The bizarre world is being called a "hot ice planet."

The finding, to be detailed in an upcoming issue of the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics, marks the first time relatively small planets similar to the ice giants Uranus and Neptune in our solar system have been found orbiting very close to their stars.

Prior to this discovery, only gaseous giants known as "hot Jupiters" were known to inhabit such close stellar quarters.

A second look

First discovered in 2004, the planet, called GJ 436 b, is about 22 times more massive than Earth. It orbits a diminutive red dwarf star 30 light-years away from us.

New observations of the planet as it "transited," or passed in front of, its parent star allowed scientists to measure its size and mass. GJ 436 b is the closest, and smallest, transiting planet to be measured in this way.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This discovery is an important step towards the detection and study of Earth-like planets," said study leader Michael Gillon of Liege University in Belgium.

Sara Seager, an extrasolar planet expert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, agrees, calling the new measurements "a huge step in the direction of finding and characterization of a habitable planet."

"It's over two times smaller than all the other planets" detected using the transit technique, she told SPACE.com. "It's a completely different kind of planet."

The measurements, made using a telescope at the Observatoire Francois-Xavier Bagnoud (OFXB) in Saint-Luc, Switzerland, revealed GJ 436 b has a diameter of about 30,000 miles (50,000 kilometers)-four times that of Earth. Based on its size and mass, scientists think the planet is composed mostly of water. If the planet were a gas giant like Jupiter or Saturn and contained mostly hydrogen and helium, it would be much larger, and if it was made up of rock and iron like Earth and Mars, it would be much smaller, the scientists say.

The water world could be enveloped by a thin atmosphere of hydrogen and helium, like Neptune and Uranus, or could be surrounded entirely by water, like Saturn's moon Enceladus.

GJ 436 b orbits its star from a distance of only about 2.5 million miles (4 million km)-about 14 times closer than Mercury's average distance from the Sun. At such close quarters, scientists think its surface temperature is at least 600 degrees Fahrenheit (300 C) and any water on its atmosphere would be in the form of steam.

Exotic ice

Water on the surface of the planet is a different matter, scientists say. The pressures on GJ 436 b are so great that water would adopt forms not found anywhere on Earth except in laboratories.

"Water has more than a dozen solid states, only one of which is our familiar ice," said study team member Frederic Pont of the University of Geneva in Switzerland.

In the same way that carbon can transform into diamonds under extreme pressures, water turns into other solid states denser than both liquid and ice under very high pressures. Physicists call these alternative forms of water Ice VII and Ice X.

"If Earth's oceans were much deeper, there would be such exotic forms of solid water at the bottom," Pont said.

Seager said the existence of different forms of ice on GJ 436 b is certainly viable, but notes there are other explanations for the results.

"For example, you could have a planet that's mostly rock like our own Earth, but just a huge version of it," she said in a telephone interview.

A planet with 20 Earth masses of rock and 2 Earth masses of hydrogen and helium in its atmosphere would also match the mass and size profile measured for GJ 436 b, Seager said.

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

- Planet Hunters Edge Closer to Their Holy Grail

- Scientists Make Ice Hotter Than Boiling Water

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.