This story was updated at 1:50 pm EDT.

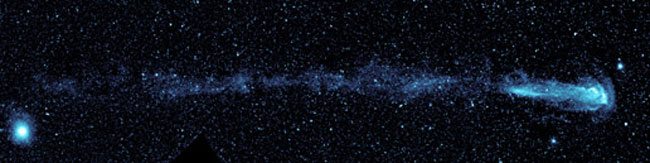

A dying star hurtling through space has left a comet-like tail that reveals its history stretching back 30,000 years.

"This is an utterly new phenomenon to us, and we are still in the process of understanding the physics involved," said study team member Mark Seibert of the Carnegie Observatories in Pasadena, California. "We hope to be able to read Mira's tail like a ticker tape to learn about the star's life."

The red-giant star, called Mira A, is streaming a comet-like tail behind it that is 13-light-years long—thousands of times the breadth of our solar system. A light-year is the distance light travels in a year, about 6 trillion miles (10 trillion kilometers). The tail is like a glowing bread-crumb trail in the sky showing the star's movements for the past 30 millennia, during which time it has shed large stores of carbon, oxygen and other elements.

"If Neanderthal man had ultraviolet eyes and could look above the atmosphere, he could have seen the beginning of this tail forming," study leader Chris Martin, an astronomer at Caltech, said in a teleconference Wednesday.

The researchers think Mira's tail might have once been much longer. "It may be that the tail slowly fades with time and we just can't see it because it's below our sensitivity level," Martin said."[Or] it may be that the star has moved into a region of the interstellar medium that is denser, and that makes the tail light up more."

Our own sun will one day become a red giant, so the finding, detailed in the Aug. 16 issue of the journal Nature, could provide valuable clues about the fate of our solar system and how stars' cast-off remains become seeds for new stars, planets and possibly even life.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A pulsing star

Located about 350 light-years from Earth, Mira is a so-called variable star that pulsates from dim to bright over a period of about 330 days. At its brightest, Mira A is visible to the naked eye. Traveling alongside Mira A is another star, either a white dwarf or a smaller version of our sun, called Mira B.

The two stars are separated by about 90 astronomical units (AU), with one AU being equal to the distance between the Earth and the sun. A previous study suggested that dust shed by Mira A is accreting into a ring around Mira B and could one day become the raw material for new planets.

The stellar pair is barreling through space at a swift 291,000 mph (468,000 kilometers per hour), possibly speeded along in their journey by occasional gravity boosts from other passing stars.

"Mira is racing through space like a speeding bullet, although it's actually 300 times faster than a bullet goes on earth," Martin said.

Scientists spotted Mira A's tail of streaming gas while using the Galaxy Evolution Explorer, an Earth-orbiting telescope, to survey the sky in ultraviolet light. Nothing of its kind has ever been observed around a star.

Visible only in UV

The streaming tail is only visible in the far ultraviolet, which might explain why it's never been seen before despite the fact that astronomers have known about Mira A for about 400 years. "We never have predicted a turbulent wake behind a star that glows only with ultraviolet light," Seibert said.

Mira A was once a star like our sun. As it aged and lost the hydrogen fuel needed to stoke its internal fires, the star swelled into a pulsating red giant. Eventually, Mira A will eject all of its remaining gas into space, forming a colorful cloud around it called a planetary nebula. This too will fade in time, and Mira A will shrivel into a burnt-out white dwarf.

The Galaxy Evolution Explorer, a project of NASA, also spotted a buildup of hot gas, called a bow shock, in front of the star, as well as two thin filaments of material coming out of the star's front and back. Astronomers think the hot gas in the bow shock is heating up the gas blowing off the star, creating a trailing tail that glows in the ultraviolet.

Michael Shara, a curator in the Department of Astrophysics at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, called the new discovery "really remarkable."

"We're seeing ourselves," Shara said. "We are seeing in a sense the process that the sun will go through in a about 4 or 5 billion years when it starts to run out of fuel and its core turns into a red giant and starts to shed material. It's also in a sense looking at where we come from. It's our origins. All the carbon in our muscles and the oxygen that we breathe everytime we take a breath comes from red giant stars."

- VIDEO: A Real Shooting Star

- Top 10 Strangest Things in Space

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.