Mystery Probed in Record-Setting Cosmic Explosion

Last September, a supernova burst into a cosmic flame 100 times more intense than any event on record—and left scientists scratching their heads.

Now, two new studies attempt to explain the remarkable explosion. One sets up the explosion with a cannibalistic star, while the other describes how colliding layers of jettisoned gas could outshine all other supernovae.

Researchers from the Netherlands and California detail their theories in today's issue of the journal Nature.

Stellar glutton

Simon Portegies Zwart, an astrophysicist at the University of Amsterdam, said supernova 2006gy's brightness was strange enough. Chemical analysis revealed something weirder.

"It possessed silicon and other heavy materials, which indicates a white dwarf," Portegies Zwart said. But the analysis also turned up hydrogen—a lightweight fuel all but converted into helium in older white dwarf stars. "The combination makes this supernova incredibly strange," he told SPACE.com.

Portegies Zwart thinks a "runaway collision" could form such an oddity; if stuck in a crowded neighborhood, such as the center of a galaxy, an old star could drag in young stellar neighbors and bring hydrogen to the party.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It would be like a chain collision on the highway. As a large star absorbs smaller ones, it grows more massive and pulls in more stars," he said. A few thousand years after cannibalizing its neighbors, the gluttonous giant would meet its demise as a supernova.

"This would be a rare event. About one in every 6,000 supernova would have similar characteristics," he said.

If the explosion fades in the next year or two, as predicted, Portegies Zwart expects to detect a dense star cluster in its place—and lend support to his team's theory.

Shell shock

Stan Woosley, an astrophysicist at the University of California Santa Cruz, also expects to see a packed stellar neighborhood when the explosion fades.

"These big massive stars are always born in dense clusters," said Woosley, whose team attempts to explain how, exactly, 2006gy burned so brightly.

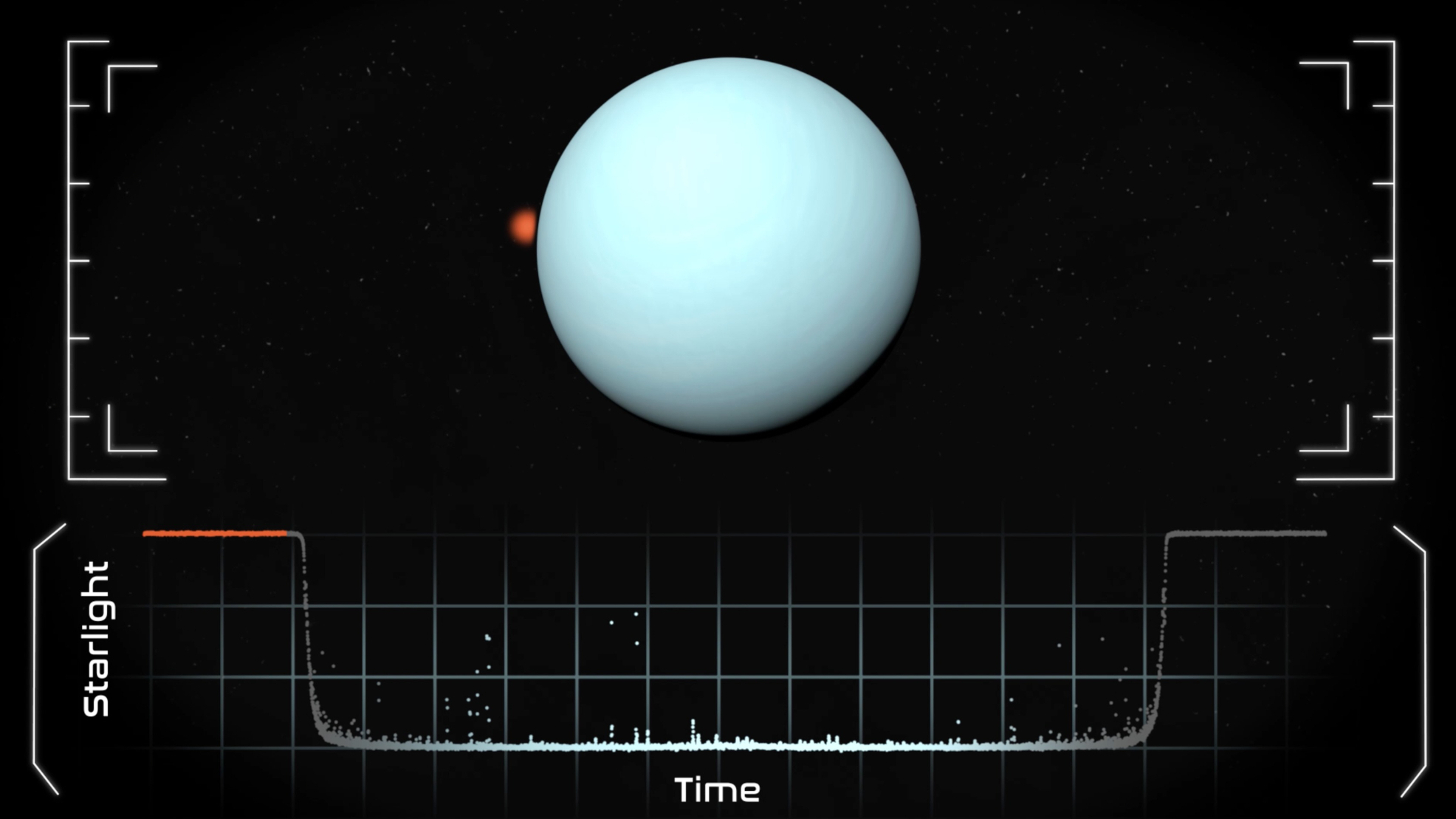

Stars about 90 to 130 times more massive than the Sun could create the unprecedented supernova as they end up fusing heavy carbon and oxygen atoms for fuel, he said. The process creates sets of annihilating particles, sucking away energy used to push gas outward—and keeping the star from exploding.

But the struggle against gravity eventually fails. When the star explodes, it rockets a shell of 20 suns worth of gas into space at more than 220,000 mph (360,000 kph).

"The star would be massive enough to explode, but not too powerful to unbind itself entirely," Woosley said, noting the event would equal roughly the Sun's entire 10 billion- year energy output in an instant.

Because the star is still intact, however, Woosley said, a second explosion would ensue about seven years later, jettisoning another gas shell at more than 2.2 million mph (3.6 million kph). "When the second, inner envelope catches up, all of that collision energy is turned into light," he said.

What's more, Woosley said, is that another bright outburst could happen again.

"Ordinarily, supernovae happen only once," Woosley said. "Our model indicates it can happen again. If it did, we'd have some pretty definitive proof."

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- Vote Now: The Strangest Things in Space

- VIDEO: The King of Supernovas

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Dave Mosher is currently a public relations executive at AST SpaceMobile, which aims to bring mobile broadband internet access to the half of humanity that currently lacks it. Before joining AST SpaceMobile, he was a senior correspondent at Insider and the online director at Popular Science. He has written for several news outlets in addition to Live Science and Space.com, including: Wired.com, National Geographic News, Scientific American, Simons Foundation and Discover Magazine.