Young Planet Orbits Sun-Like Star

Astronomerssay they have discovered the youngest planet to date circling a sun-like star,a find that will be a boon to the field of planet-formation theory.

Theextrasolar planet is an estimated 8 million to 10 million years old, a meretoddler compared to Earth, which is 4.5 billion years old. Until now, theresearchers say, no planet younger than 100 million years old has been detectedcircling a sun-like star.

"Itmeans we're opening up a new field of trying to find planets around very youngstars," said Alan Boss, a planet-formation theorist at the CarnegieInstitution of Washington. "So it's the very first example, and we hopethere will be a lot more." Boss was not involved in the discovery.

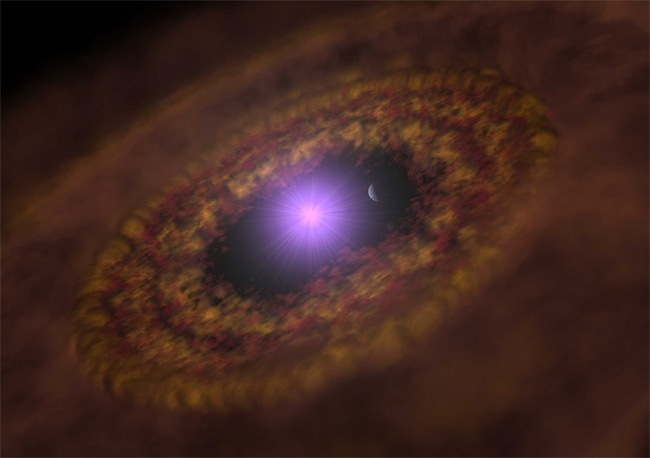

The newlyfound world is so infantile that it resides in the star's "protoplanetarydisk," a ring of gas and dust circling the star. It has been catalogued asTW Hya b.

"Thisdemonstrates that planets can form within 10 million years, before the disk hasbeen dissipated by stellar winds and radiation," the researchers write inthe Jan. 3 issue of the journal Nature.

Weighing inat nearly 10 Jupiter masses, the planet circles at a distance of .04Astronomical Units (AU) from its host star, TW Hydrae, in the constellationHydra. One AU is the average distance between the Earth and sun.

The gassy"hot Jupiter" takes 3.56 days to orbit its star. The host star islocated 180 light-years away from Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Planets arethought to form within disks of dust and gas around newly born stars. Catchinga planetin its childhood can give astronomers lots of information about how planetsmaterialize.

"Thediscovery shows that what we always call as 'protoplanetary' disks are indeedprotoplanetary; they form planets," study researcher Johny Setiawan of theMax-Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany told SPACE.com."There are many 'protoplanetary' disks detected around young stars, but noplanets so far have been detected within such young systems."

Around someyoung star systems, however, astronomers have found signsof planets by noting clear lanes of dust within the disks. In these cases,it's presumed that young planets are forming and have scooped up the dust, butthe planets themselves have not been detected.

Setiawanand colleagues discovered their new world by measuring a wobble in the hoststar due to the gravitational tug from the orbiting planet. This so-calledradial-velocity method is great at detecting extrasolar planets, but it alsocan produce false positives — suggesting a planet is there when in fact the dataowe to some other object or phenomenon.

That'sparticularly true in young star systems. For one, nascent stars are incrediblyactive and their changing outer atmospheres can at the very least make forbackground noise. In addition, if the star rotates about its axis, that can beproblematic.

"Thereare lots of other things going on in these young stars that could give you afalse positive, where you think you're seeing a planet but you're actuallyseeing some other stellar activity," Boss said in a telephone interview.

Boss thinksthe discoverers ruled out these non-planet signals. "They've done a good job of trying toaddress those worries," he said.

- Top 10 Strangest Things in Space

- Video: Planet Hunter

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Exoplanets