Newly Found Martian Salt Deposits Suggest Ancient Life

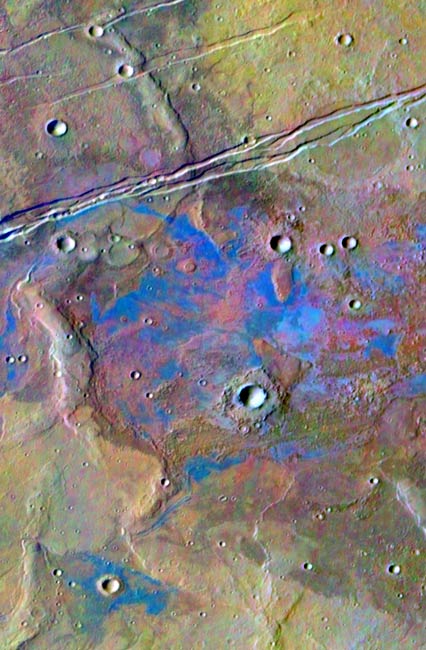

For thefirst time, satellite imagery reveals thick Martian salt deposits scatteredacross the planet's southern surface, which one planetary scientist claims couldbe sites of ancient life.

The mats ofsodium chloride — the same taste-enhancing mineral found on your kitchen table— serve as more evidence of Mars' watery past, and researchersthink the briney pools that made them could have been hospitableto life.

"Ifyou're trying to find life on Mars, the more and different places that exist,the better the chances are that one of them is going to have the right conditions,"said Phil Christensen, a planetary geologist at Arizona State University."It takes a lot of water to form salt, so this is another place tolook."

Christensen,who co-authored a March 21st study in the journal Science detailing thefindings, said the salt deposits are a clear sign of water's past presence, addingthat they could be the most welcoming environment for life on Mars yet discovered.

Take achance

Christensensaid the salt deposits probably formed from dried-up brine pools,which would not have been as acidic as other places on Mars where water isthought to have existed, such as clay and hydrated mineral deposits.

Sites suchas those found by the Mars Exploration Rovers show sulfur in high levels, whichmeans any water there may have been too harsh to support life.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"That'snot the case with salt deposits, because they tend to not be acidic,"Christensen said.

He addedthat some of the oldest organisms ever discovered on Earth have been foundlocked away in salt crystals, and that there may be Martian life forms entombed in the new crumbly flats that are about 3 to 10 feet (1 to 3 meters) thick.

"Saltis a fantastically good preserver, so maybe there's not only life but also organiccompounds preserved there," Christensen told SPACE.com. "Weneed to send a rover to these places. I hope some day we will explore thesesalt sites on the ground."

Transparenttreasure

Christensensaid the route to identifying the salt deposits, thought to be more than 3.5billion Earth years old, wasn't easy.

"Salt,it turns out, is pretty hard to detect," Christensen said, explaining thatlight analysis, or spectroscopy, of the mineral doesn?t often show clear-cutsignatures in satellite data. "They're actually very transparent, sothere's generally a lot of difficulty in identifying them."

Using the MarsOdyssey orbiter's Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS),the research team found dozens of strange sites in a belt just south of Mars'equator. Christensen said it took them a couple of years to figure out what,exactly, they were.

"Oncewe realized we were looking at a transparent mineral, the light bulbs in ourheads went off," he said. "When you look at the sites with visual satelliteimages, they look all the world like dried-up salt flats."

Saltyskepticism?

Christensensaid a handful of planetary scientists are likely to be skeptical of his team'sconclusion, but noted that a large majority should be on board.

"The spectroscopyof these salt sites is complicated, so I don't expect everyone will agree withus," he said. "Salts do this bizarre thing to spectrographs, so we haveto do more singing and dancing to make the case."

In anyevent, Christensen said the sites he and his team have pinpointed are worthy offuture investigation, especially if other ancient Martianwater sites don't pan out to support life.

"Ialways worry that someone will say that's the end of the story for life on Marsif that happens," Christensen said. "I think these salt sites arereally exciting. They may give us the best chance yet of finding something."

NASA fundedthe work by Christensen and his team.

- VIDEO: Looking For Life in All the Right Places

- VIDEO: Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter

- GALLERY: Ice on Mars

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Dave Mosher is currently a public relations executive at AST SpaceMobile, which aims to bring mobile broadband internet access to the half of humanity that currently lacks it. Before joining AST SpaceMobile, he was a senior correspondent at Insider and the online director at Popular Science. He has written for several news outlets in addition to Live Science and Space.com, including: Wired.com, National Geographic News, Scientific American, Simons Foundation and Discover Magazine.