Marching Sand Dunes Create Mars Mystery

Sand grainsstirred up by the winds of Mars are tossed higher and farther than those kickedup by winds on Earth, a new study finds. The results could help explain howdunes migrate across the Martian surface as well as what whips up dust storms thatblow across the red planet.

Scientistsfirst noticed dunes on the Martian surface in pictures taken by NASA's Marinermissions in the 1970s and have seen dust storms of all sizes spread across theplanet ? onemajor storm in 2005 was even visible through a simple backyard telescope. Butthese features have puzzled astronomers because Mars has almost no atmosphereand very weak winds that seem unlikely to be able to sculpt dunes or whip upstorms.

To help solvethis conundrum, a team of scientists recently conducted wind tunnel simulationsof windblown sand grains under the conditions found on both Earth and Mars tofigure out how the particles would behave on these planets with vastly differentatmospheres. Their results are detailed in the April 28 issue of the journal Proceedingsof the National Academy of Sciences.

Sandcollisions

Winds tendto move particles in one of three ways. When the particles are heavy,"they cannot be lifted off from the ground by the wind, so they remainvery close to the ground," a process aptly called "creep,"explained study team member Eric Parteli of the Universidade Federal do Cear?in Brazil. On the other hand, lighter particles can hang around in theatmosphere for awhile and travel over long distances.

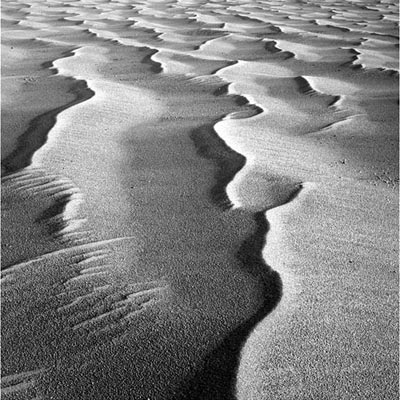

In betweenthese extremes, a process called "saltation" reigns. Wind turbulencekicks up a sand particle and carries it along in a series of jumps, finallydropping it to the ground where it collides with other particles and in turnknocks them up into the air, Parteli said.

Saltationis what creates the iconic sand dunes of the Sahara and other deserts on Earthas the sand particles accumulate into mounds, usually with gentler slopes ontheir windward sides. With the discovery of duneson Mars, scientists thought the process might occur on our red neighbor aswell.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Weonly know that saltation occurs on Mars because we see that there aredunes," Parteli said.

Butscientists were unsure if the dunes were simply relics of Mars' past, when itsatmosphere was denser and capable of generating stronger winds than it is now.The planet's current atmosphere is less dense than Earth's, and wind speeds 10times faster than those on Earth would be required to pick up Martian sandparticles.

"So weknow actually that the winds ofMars are actually very weak," Parteli told SPACE.com."They remain very much below the minimum threshold for saltation all thetime."

Dunemigration, also caused by saltation, has only been noticed on the red planet ina few before-and-after images in the last couple years, which seemed toindicate that saltation could still be going on, at least in some areas of theMartian surface.

Parteli andhis colleagues used wind tunnel simulations that took into account thedifference between the Martian and terrestrial atmospheres (in terms of suchparameters as pressure and temperature) to see if Martian winds could generatesaltation events.

Theirexperiments and models showed that the winds could in fact eject particles fromthe surface. And not only that ? the particles went higher and traveled fartheron Mars than on Earth, because Mars' gravity is weaker (approximately one-thirdof Earth's gravity).

"Theparticle is allowed to remain longer in the atmosphere," Parteli said. "Itis not pushed downward by the gravity so strongly as it is on Earth."

Theresearch was funded by the Conselho Nacional de Pesquisas (CNPq), the Comissaode Aperfei?oamento de Pessoal de Nival Superior (CAPES), the Funda??o Cearensede Amparo ? Pesquisa (FUNCAP), the Volkswagenstiftung and the Max-Planck Prize.

Dunesand dust storms

ThoughParteli and his team's results show that saltation can occur if the winds arestrong enough, the winds on Mars rarely reach above the proper threshold, whichmakes saltation "a very seldom event on Mars," Parteli said.

Strongwinds could be confined to particular regions of Mars, said Kevin Williams ofBuffalo State College, who was not affiliated with the new study. These windscould rush down from the polar ice caps and stir up sands in nearby regions, henoted. Another possibility is that it might be easier for wind to move fasterin low-lying areas where the air is slightly denser, he told SPACE.com.

The newstudy provides "progress in understanding the overall process of sandsaltation on Mars," Williams said.

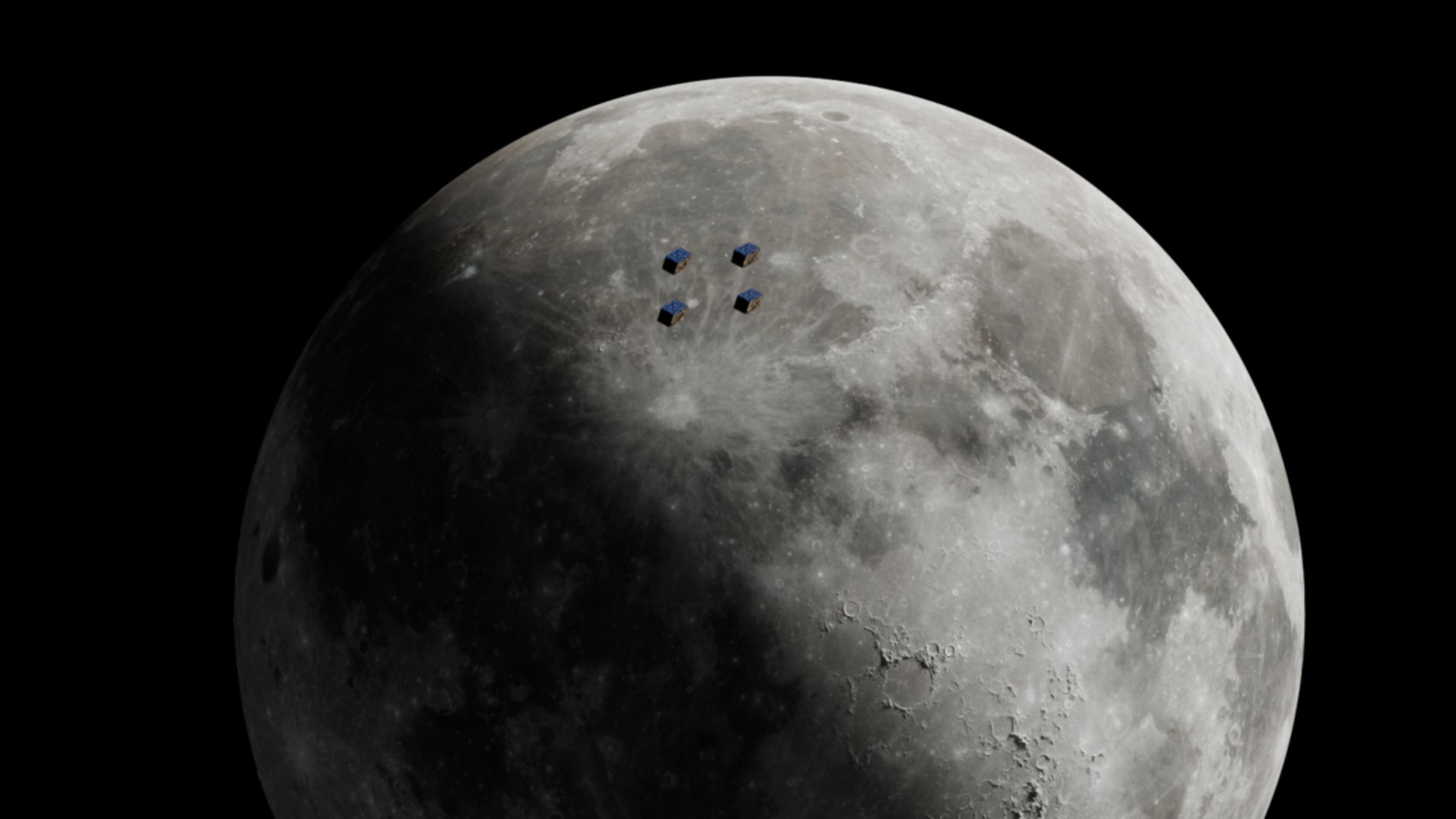

The shapesof dunes in certain areas of Mars could shed light on the winds there, as duneshape is largely a function of wind direction. The most common type of dune (onboth Earth and Mars), called barchans, are shaped by winds blowing in just onedirection, while another type, called longitudinal, are formed by winds blowingin two directions. The shapes of dunes on Mars have been likened to the videogame character Pac-Man,horseshoe crabs and worms.

Wind speedcan also affect dune shape, with stronger winds producing taller, narrowerdunes than lighter winds.

Saltationis also a suspected cause of the ruddy dust storms that can blow across theMartian landscape. The saltating sand particles could eject dust from thesurface as they are dropped, Parteli said, though he noted that other factors,such as temperature change, are also suspected causes. Ultimately, "howdust storms form is actually an open question," he said.

- Mars Madness: A Multimedia Adventure!

- Vote: The Best of the Mars Rovers!

- Images: Visualizations of Mars

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.