Supernova Birth Observed for First Time

Whilepeering at her computer screen four months ago, astronomer Alicia Soderbergexpected to see the small glowing smudge of a month-old supernova. But what sheand her colleague saw instead was a strange, extremely bright, five-minuteburst of X-rays.

With thatobservation, they became the first astronomers to catch a star in the actof exploding.

"Foryears we have dreamed of seeing a star just as it was exploding, but actuallyfinding one is a once-in-a-lifetime, event," said Soderberg, a Hubble andCarnegie Princeton Fellow at Princeton University.

Thediscovery, detailed in the May 22 issue of the journal Nature, will shedlight on the early stages of this violentstellar death, acting as a deciphering key or "Rosetta Stone" forsupernova studies, as Soderberg puts it.

Andanalysis of the energy emitted by the new supernova, dubbed SN 2008D, couldhelp astronomers better understand this explosive process and the properties ofthe stars that lead to it.

X-ray'breakout'

A typical supernova occurs when the core of amassive star runs out of nuclear fuel and collapses under its own gravity toform an ultradense object known as a neutron star. But only so much materialcan compress into the neutron star, so some of the original star's collapsinggaseous outer layers can't fit; instead, they simply bounce off the neutronstar, Soderberg explained, triggering a shock wave that plows back through the outerlayers and blows the star to smithereens.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronomershad predicted for decades that this "breakout" phase would produce anX-ray blast lasting several minutes, but until Soderberg and Princetonpostdoctoral researcher Edo Berger's discovery, no one had ever observed thesignal. Supernovas were only found as they brightened days or weeks after theirinitial explosion.

"Usingthe most powerful radio, optical and X-ray telescopes on the ground and inspace, we were eventually able to observe the evolution of the explosion rightfrom the start," Berger said. "This eventually confirmed that the bigX-ray blast marked the birth of a supernova."

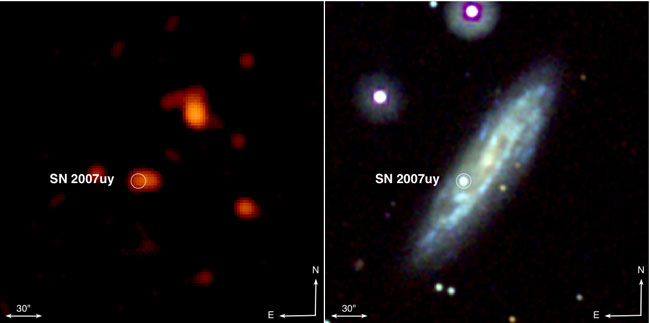

Thediscovery was a case of serendipity, Soderberg said, as the team had NASA'sSwift satellite pointed at NGC 2770 to observe supernova SN 2007uy (located 90million light years from Earth in the constellation Lynx) and happened to catchthe X-ray outburst.

"Wewere in the right place, at the right time, with the right telescope on January9th and witnessed history," Soderberg said.

World-widemonitoring

Afterobserving the X-ray outburst, Soderberg mounted an international observingcampaign, with telescopes all over the world joining in to monitor the babysupernova, including the Hubble Space Telescope, the Gemini South Telescope in Chile, Lick Observatory and the Keck I telescope in Hawaii, among others.

Thecombined observations helped to pin down the energy of the initial X-ray burstand showed that it was a typical Type Ibc supernova, which occurs when a massive,compact star explodes.

Theobservations will also provide insight into the early stages of supernovas.

"Thisfirst instance of catching the X-ray signature of stellar death is going tohelp us fill in a lot of gaps about the properties of massive stars, the birthof neutron stars and black holes, and the impact of supernovae on theirenvironments," said Neil Gehrels, principal investigator of the Swiftsatellite.

Studyingthis initial X-ray outburst will also give astronomers a signature to help themspy other newborn supernovas and set their time of explosion to within a fewseconds, instead of a few days like previous timing estimates.

"Wealso now know what X-ray pattern to look for," Gehrels said."Hopefully we will be able to find many more supernovae at this criticalmoment."

- Video: Supernova Destroyer/Creator

- Vote Now: The Strangest Things in Space

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.