Proof! Water Ice Found on Mars

Scientists said today they have "found proof" ofwater ice on Mars away from the polar ice caps, a discovery made by NASA'sPhoenix Mars Lander.

The finding is a crucial first step toward learningwhether the ground on Mars is hospitable, because all life as we know it requireswater. Now scientists can get on with the business of studying the chemistry ofMars dirt in more detail.

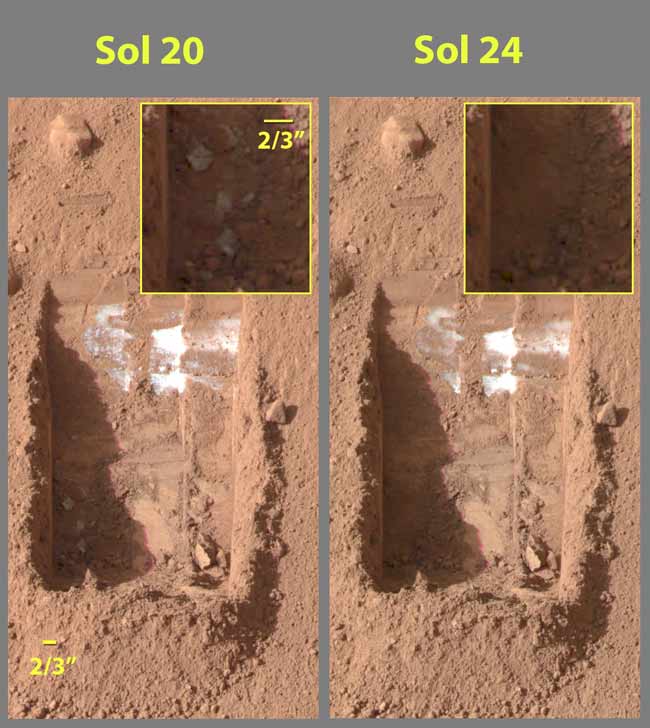

When the probe took photos of a ditch it had dug four daysbefore, scientists noticed that about eight small crumbs of a bright materialhad disappeared. They concluded those crumbs had been water ice buried under athin layer of dirt that vaporized when Phoenix exposed them to the air.

"It's with great pride and a lot of joy I announcetoday we have found proof that this hard material really is water ice and notsome other substance," Phoenix principal investigator Peter Smith of theUniversity of Arizona, Tucson said at a briefing Friday.

The finding had been discussed tentatively yesterday, but ina press conference today, researchers left no doubts.

Phoenix's robotic arm first revealed the crumbs about 5 cmdeep in the trench called "Dodo-Goldilocks" on June 15. By June 19,they had vanished. If the crumbs had been salt, they wouldn't have disappeared,scientists said, and if the ice had been made of carbon dioxide, they wouldn'thave vaporized.

"What this tells us is we found what we're lookingfor," said Mark Lemmon, a Phoenix co-investigator from Texas A&MUniversity. "This tells us that we've got water ice within reach of the [robotic]arms, which means that we can continue the investigation."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The $420million mission landed on the arctic plains of Mars May 25,embarking on a quest of at least four months to search for signs that theenvironment was once habitable to life.

A "significant result"

Finding ice on Mars isn't completely shocking, sinceobservations from past satellites sent to orbit the planet, such as the 2001Mars Odyssey spacecraft, have indicated that ice is likely to lie beneath the planet'ssurface. Still, if confirmed, this would be the first direct finding of thatice by a probe on the ground.

??We certainly expected to find ice there," said BruceJakosky, a geologist at the University of Colorado who has been involved withpast missions to the red planet. "It was the [previous] evidence for icethat sent us to that location. But there?s a difference between expecting itand finding.?

Jakosky called the discovery a ?significant result? thatallows the Phoenix mission to go forward with its wet chemistry experiments,analyzing the soil for the history and composition of the ice.

?If they had found no ice, which was a real possibility, thatwould make this much harder,? he told SPACE.com. ?I?m anxious to see theresults of the chemical analysis.?

And although the 2001 Mars Odyssey satellite could measurethe average water ice content in roughly the top meter ofground over areas of several hundred kilometers, these data didn'treveal how that ice was spread out, said Maria Zuber, a geophysicist at MIT whoworked on past Mars missions, including the Spirit rover.

"We don't know the form of the water, beyond the factthat there is too much there to be explained solely by water bound inminerals," Zuber said. "So chunks, a layer, etc. are allpossibilities. The [Phoenix] observation is an important advance in ourunderstanding of water on Mars, and continued sampling willundoubtedly add to the story."

Next steps

The next questions to answer are what chemicals, mineralsand organic compounds might be mixed in with the water.

"Just the fact that there's ice there doesn't tell youif it's habitable," Smith said. "With ice and no food it's not ahabitable zone. We don?t eat rocks ? we have to have carbon chain materialsthat we ingest into our bodies to create new cells and give us energy. That?swhat we eat and that's what has to be there if you're going to have a habitablezone on Mars."

To find this out, mission scientists plan to eventually putsamples of ice into Phoenix's oven instrument, the Thermal and Evolved-GasAnalyzer (TEGA), which is designed to bake Martian dirt and analyze the vaporsit emits to detectits composition. They also plan to use the onboard Microscopy,Electrochemistry and Conductivity Analyzer (MECA) instrument, a wet chemistrylab that measures levels of acidity, minerals, and conductivity in dirtsamples.

"Now we know for sure that we are on an icy surface andwe can really meet the science goals of our mission at the highest level,"Lemmon said. "I am just sitting at the edge of my chair waiting to findout what the TEGA and MECA can tell us about these soils."

Expect the unexpected

Although the ice finding was expected, until Phoenixactually found it, many scientists were still holding their breath.

"As for the ice, we were expecting to find it, butscience is full of the unexpected, so until they actually found the ice and canbegin to study it there are real questions about whether or not the hypothesiswas correct," said Phil Christensen, a geophysicist at Arizona StateUniversity who worked on 2001 Mars Odyssey, Mars Global Surveyor, and the MarsExploration Rover missions. "The real excitement will come when they startto study the ice in detail and attempt to learn how it formed and how old itis."

Additional reporting for this article was contributed byJeremy Hsu, SPACE.com staff writer.

- Video: Digging on Mars

- Video: NASA's Phoenix: Rising to the Red Planet

- New Images: Phoenix on Mars!

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.