Melting Glaciers Sculpted Mars Gullies

Some of the gullies that cut the sides of Martian craters were likely formed by meltwater from glaciers that existed a few million years ago, when Mars was wetter than it is now, a new study suggests.

The gully features are similar to ones seen in the Dry Valleys of Antarctica, say the authors of the study, which is detailed in the Aug. 25 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. So this polar region of Earth can act as an analog for Mars' past.

The gullies, young features geologically speaking, were discovered in 2000 by NASA's orbiting Mars Global Surveyor, which is now out of commission. The discovery came as a surprise because scientists had thought that Mars was too dry in the past few million years to host liquid water at its surface, as it is today.

Though water ice was confirmed this summer by NASA's Phoenix Mars Lander just a few inches below the surface of Mars' arctic regions, the planet's below-freezing temperatures and low atmospheric pressure ensure that any ice exposed to the air turns into vapor.

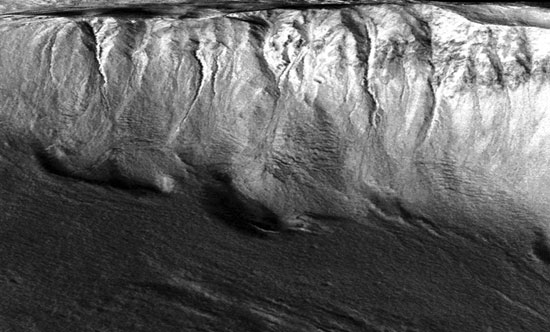

When the gullies were discovered, some scientists proposed that the features were formed either by dry avalanches or by groundwater pushing up from below the surface and running down the sides of craters. But in a study of gullies within a 6.5 mile- (10.5 kilometer-) diameter crater located in the much larger Newton Crater, James Head of Brown University and his colleagues found that accumulated ice and snow were more likely the source of the water that sculpted the gullies.

Ice ages

Head and his team examined high-resolution images of the crater and its gullies taken by orbiting spacecraft and found evidence of features that suggested glaciers once covered the crater floor about 10 million to 20 million years ago.

As Mars' orbit and planetary tilt (with respect to the sun) changed as a result of the natural wobble of the planet's axis, glaciation waned, and the bulk of the ice was lost. As the ice started to sublimate (or vaporize), debris embedded within it began to pile up on the crater floor. These deposits can be seen on the crater floors now, said study team member David Marchant of Boston University.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But debris didn't accumulate as much on the crater walls, leaving behind hollows where the glaciers once sat. "Where ice used to stand you have a hole," Marchant told SPACE.com.

As the climate continued to change, not enough snow fell to maintain the glaciers, and the holes left by the glaciers could have caught windblown snow and preserved it in drifts. In the summer, these drifts were likely exposed to warmer summer temperatures, melting the snow and ice deposits, which then ran down the crater slopes, eroding the sediment and forming the channels and fans of the gullies.

Glacier vs. groundwater

These findings likely rule out the other mechanisms proposed for creating the gullies — gurgling groundwater and dry avalanches — in this and other craters, Marchant said.

There's no geological evidence for dry avalanches, and for groundwater to be the cause, melting would have had to penetrate to the subsurface. "It's a much more difficult thing to do," Marchant said. "It's much easier just to melt the surface snow."

Because this new study, funded by NASA and the National Science Foundation, shows that glaciers pre-existed the gullies, it seems likely that melting snow and ice are behind the gully formations.

"It just seems to fit the geologic story," Marchant said. "For geology it's all about the sequence of events."

Antarctic analog

Meltwater in Earth's Antarctic Dry Valleys — also a very dry region — seems to create some of the same patterns in gully fans as are in seen on Mars. Head and his colleagues have done field work in the Dry Valleys to better understand the processes that sculpt the Martian gullies.

The team suspects that some of the pockets in these gullies might have held water in various forms in the recent past, over the last few hundreds of thousands of years, periodically harboring snow and ice when the conditions were right. The researchers also think that the Antarctic gullies would be a good area for close-up study because of the relatively recent interaction between water and the Martian surface.

"It would be great to have a rover explore these deposits because they may be one of the few places where water is periodically present in the recent past. This could have implications for biology," Head told SPACE.com in an email. Water has long been considered a requisite feature for any potential Martian life as it is key to life as we know it on Earth.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.