Black Holes Burp Big Bubbles

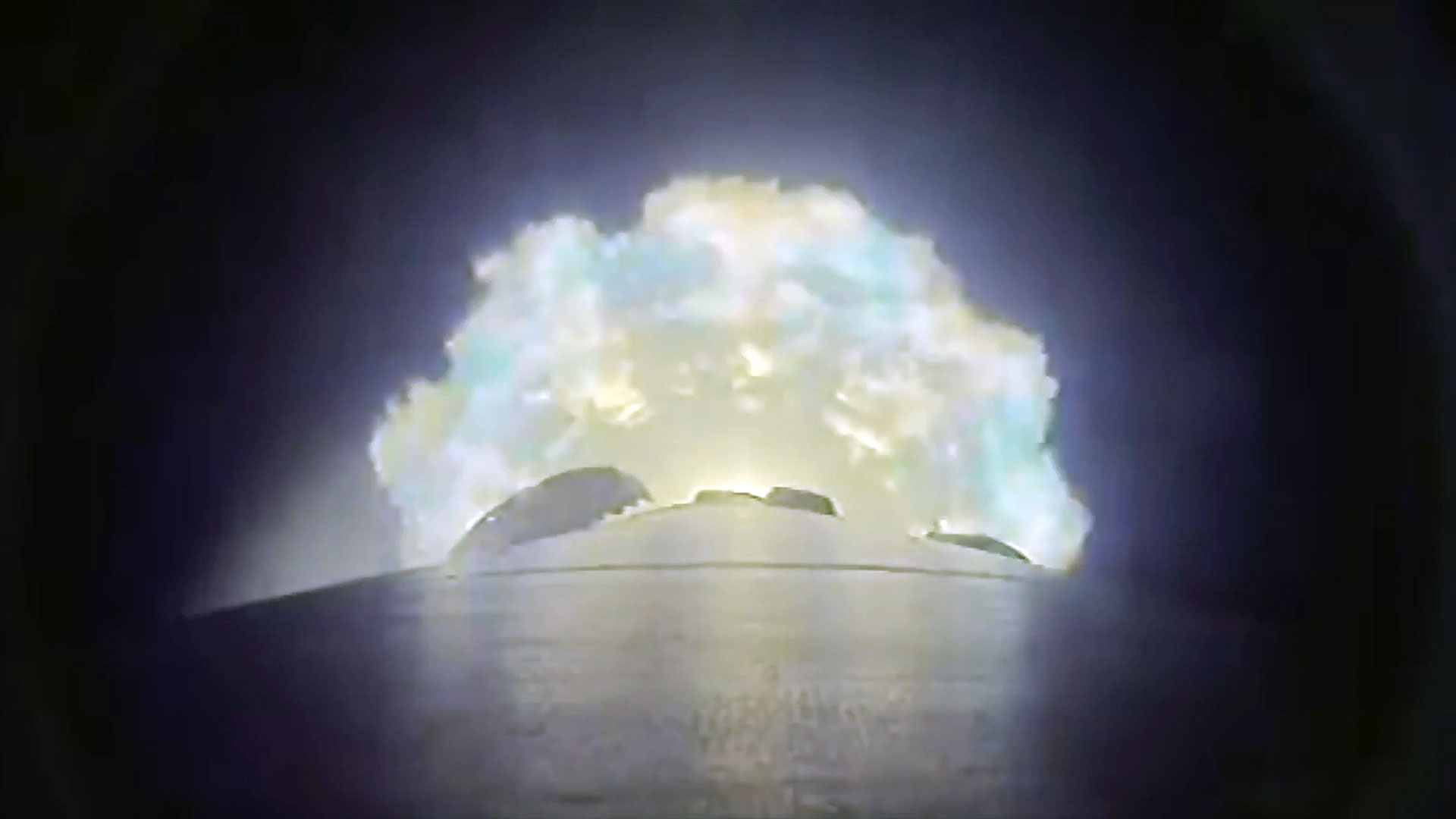

Like cosmic bubble makers,some black holes spew out behemoth blobs of hot gas into their home galaxies.

The bubbles ultimately pop,and their gassy contents keep both the black hole and its galaxy fromballooning to mega sizes, a new study finds.

The results apply toelliptical galaxies and their supermassiveblack holes, which can weigh as much as a billion suns or more. Our galaxy,the MilkyWay, is a spiral galaxy. And while it houses a supermassive black hole, theresearchers say the same process might not apply to it.

Black hole bubbles

The researchers focused onthe supermassive black hole at the center of the elliptical galaxy M84, whichis about 55 million light-years from Earth. (A light-year is the distancelight will travel in a year, or about 6 trillion miles, or 10 trillion km.)They combined data collected by NASA?sChandra X-Ray Observatory and results from a black-hole computer simulation.

They noticed huge bubbles,or cavities, of hot plasma (ionized gas) rising up from the tips of the blackhole's pair of laser-like jets. (As material falls into the gravitationalclutches of a black hole, the energy can be spit out as jets of radiation andhigh-speed particles.) They estimate the bubbles are about 13,000 light-yearsacross and they are launched from jets about every 10 million years.

The X-ray images showedthat, like Russian dolls, each bubble has a smaller bubble tucked inside of itand so on. When the outer bubble bursts, spilling its gaseous guts, there'sanother inside waiting to pop as well. That continuous bubble-popping providesa constant input of heat into the surrounding interstellar gas.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We think certain instabilitiesare formed on the interface between the bubble and the surrounding medium andthese instabilities shred and puncture this bubble, and the stuff that isinside them, this hot plasma, is spilling out and mixing with the surroundinggas," said researcher Mateusz Ruszkowski, an astronomer at the Universityof Michigan.

Cosmic diet

The jolts of heat stem thefood supply to the central black hole and slow down star formation nearby.

Over time, black holesgrow in heft as their gravity pulls in surrounding gases. Because cool gas isdenser, it sinks to the center of galaxies ? and toward the black hole ?faster. If the gas around the black hole is kept warm, it sinks toward theblack hole at a slower rate.

"In this way, you canfeed the black hole and add more and more mass to it," Ruszkowski told SPACE.com."If there's no mechanism to prevent the cooling that is essentiallytriggering this feeding process then the black hole would grow in anuncontrollable fashion."

But, he added, "nobodyin the field thinks this is happening," he said. The new results, which aredetailed in the Oct. 20 issue of Astrophysical Journal, reveal amechanism for continuous heating of the interstellar material, he said.

A similar mechanism keepsstar formation in check and in turn the mass of the home galaxy.

Stars are thought to form asdense clouds of gas and dust collapse under their gravity. Over time, thematerial heats up and ultimately the tight bundle becomes a full-fledged starpowered by thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen and other light elements in itscore.

The cooler the material, themore likely the clumps of gas and dust will succumb to the force of gravity andcollapse into luminous stars.

- Video: Black Holes: Warping Space and Time

- Video - How Stars Form Near Black Holes

- Vote: The Strangest Things in Space