Explosions Starve Black Holes

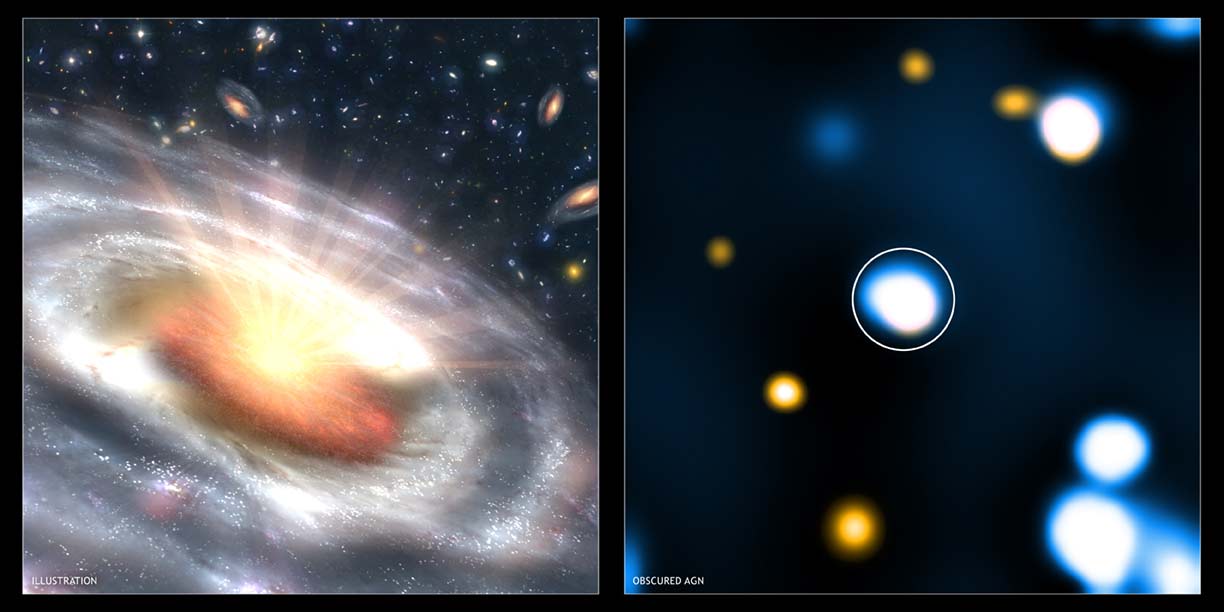

LONG BEACH,Calif. - Supermassive black holes are thought to lurk at the heart ofessentially all galaxies bigger than our own. Their powerful gravity should be luringin galactic matter, feeding the black holes' voracious appetites.

However, whileplenty of gas is available for these blackholes to feast upon, few of them have been observed to activelyaccrete gas from their home galaxy, presenting astronomers with a puzzle asto why these black holes aren't eating. Something must be preventing the blackholes from accreting gas, though no one has known exactly what that was.

"Thishas been a longstanding problem," said Q. Daniel Wang of the University ofMassachusetts at Amherst.

Now, Wangand his colleagues have some possible suspects behind the starving black holes:exploding stars, or supernovas.

Wang andhis team investigated the starvation of the supermassive black holes at thecenter of two galaxies, M31 (aka the Andromeda Galaxy, our nearest galacticneighbor) and NGC 5866. They presented their findings here this week at the213th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

With bothof these galaxies, and others, the precise clue that the galaxies aren'tfeeding is the lack of large amounts of radiation coming from the nucleus ofthe galaxy, which astronomers would expect to detect from an actively eatingblack hole. What makes the lack of radiation most perplexing is that plenty ofgas should be expelled by older stars and their remnants, such as planetary nebulas, and accumulating inthe galactic bulges of the galaxies (the tightly-packed group of stars found inthe center of galaxies, where the black hole resides).

What washappening to that gas has been a mystery. Astronomers had surmised that the gas"has to be removed continuously from the bulge," Wang said, otherwisethe black holes would be feasting on it.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Someastronomers thought gravitational influences from nearby galaxies could besucking away the gas. But Wang's study suggests it's actually an internalproblem generated by powerful supernova explosions.

Theseexplosions occur when a massive star's core stops generating energy andcollapses in on itself, releasing energy that heats and expels the star's outerlayers - the star goes supernova.

Supernovascome in slightly varying types.

Type 1a supernovasare constantly exploding throughout a given galaxy. These exploding stars sendout a shockwave - what Wang calls an "interstellar tsunami" - thatpropagates throughout the gas in the galaxy. Wang and his team simulated theeffect of these shockwaves on the gas accumulation around the galaxy?s center.

Theinterstellar tsunami works in a similar manner to tsunamis on Earth: Theshockwave generated by an earthquake below the ocean has little effect wherethe ocean is deep and can absorb the energy, but when that wave reaches shallowwater, it forms the characteristic enormous wave that slams onto the coast.

Likewise,the hot gas in the galaxy can absorb the supernova's shock, but when the wavereaches the cool gas expelled by dying stars, it steepens and pounds thecentral disk of the galaxy, evaporating the gas.

Becausethese supernova explosions are happening all the time, they continue to poundaway at the disk; the gravity of a less massive galaxy can't counteract theevaporating energy of the supernovae, so the gas can?t accumulate, and theblack hole starves.

Theinterruption of the gas accumulation also affects the evolution of the galaxy,Wang noted.

Moremassive galaxies, on the other hand, have a bigger gravitational pull thatkeeps the gas from leaving.

"It?sa much more difficult escape," Wang told SPACE.com."Eventually gravity wins."

- Video:Black Hole Diving

- BlackHoles Preceded Galaxies, Discovery Suggests

- Vote Now: The StrangestThings in Space

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.