Gullies Mark Most Recent Water Flow on Mars

Water ispresent on Mars today, but it is entirely bound up in ice because the surfaceis too cold for liquid water.

Butevidence has been mounting that shows water once flowed across the Martiansurface, potentially supporting life. While water does not mean there was life,it's a key prerequisite.

A new studyof a system of gullies worn into the surface of Mars suggests the most recentperiod of water flow on the red planet was only 1.25 million years ago.

Butthroughout the more than 4 billion-year history of our neighbor, its climatehas cycledback and forth between warmer and cooler periods as the planet wobbled onits axis. Like Earth, Mars' axis is tilted with respect to its orbital planeand the degree of tilt changes over thousands of years. But Mars' tilt changesmore over time, alternately heating up or cooling down parts of the planet asthe amount of sunlight falling on them changes.

Over the pastdecade, scientists have found numerous geological features, such as gullies andpossible lakebeds, that indicate water was once present on the surface. Theyhave also foundwater-bearing minerals, such as opals and carbonates that show that waterhas reacted with the Martian regolith, or dirt.

Gulliesare known to be young surface features on Mars, but pinning a precise date tothem has been difficult.

The newstudy, detailed in the March issue of the journal Geology, did just thatwith a gully system located on the inside of a crater in Promethei Terra,showing that water flowed on Mars more recently than previously thought.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Wethink there was recent water on Mars," said study team member Jim Head of Brown University in Providence, R.I. "This is a big step in the direction to provingthat."

Cratercounting

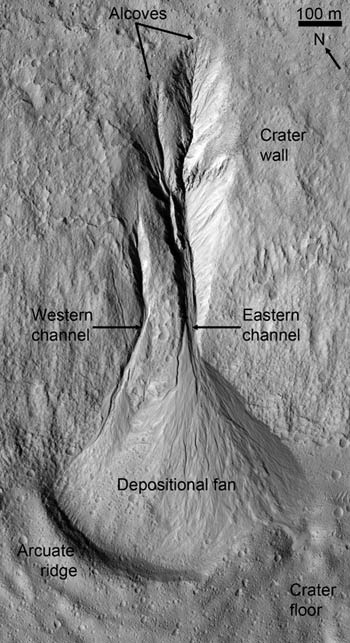

The gullysystem the team examined shows that water-borne sediments were carried downsteep slopes of nearby alcoves and deposited in a fan-like shape during fourdifferent intervals.

"Younever end up with a pond that you can put goldfish in," said study teammember Samuel Schon, a graduate student at Brown. "You had ice thattypically sublimates. But in these instances, it melted, transported, anddeposited sediment in the fan. It didn't last long, but it happened."

Viewed fromfar away, the fan looks like one continuous feature, but close-up images takenby the NASA MarsReconnaissance Orbiter HiRISE camera show four distinct lobes in thealluvial fan.

Schon wasable to determine that the lobes were created at different times and could tellwhich was the oldest because it was pockmarked with craters, while the youngerlobes were left relatively unblemished. (The longer a surface has been exposed,the more meteorites have had a chance to leave their mark.)

Schonlinked the craters in the oldest lobe of the fan to a rayed crater more than 50miles (80 kilometers) to the southwest. He dated the crater to about 1.25million years, which meant the younger lobes of the fan could not be any olderthan that.

The teamalso determined that ice and snow deposits formed in the alcoves when Mars wastilted so that it plunged into an ice age and ice could form in themid-latitude areas, instead of being confined to the poles, as it is today.About half a million years ago, the planet's tilt change and the ice began tomelt or sublimate.

Schon saidthat other explanations for the water's presence in the gully were ruled out:Groundwater bubbling up seemed unlikely to have occurred multiple times, anddry mass wasting (for example, a rockslide) also didn't seem to fit thepattern.

Thefindings add more evidence that Mars underwent a recent, geologically-speaking,ice age that moved water closer to the equator of the planet.

- Zoom In: Water on Mars?

- Mars Madness: A Multimedia Adventure!

- Images: Ice on Mars

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.