New Origin for 'Pillars of Creation' Suggested

The origin of the majestic "pillars of creation,"one of the most familiar and colorful scenes in space, is a bit of a mystery.Now researchers say it might have started from gaseous clumps pushed intoshadowed areas by radiation from nearby stars.

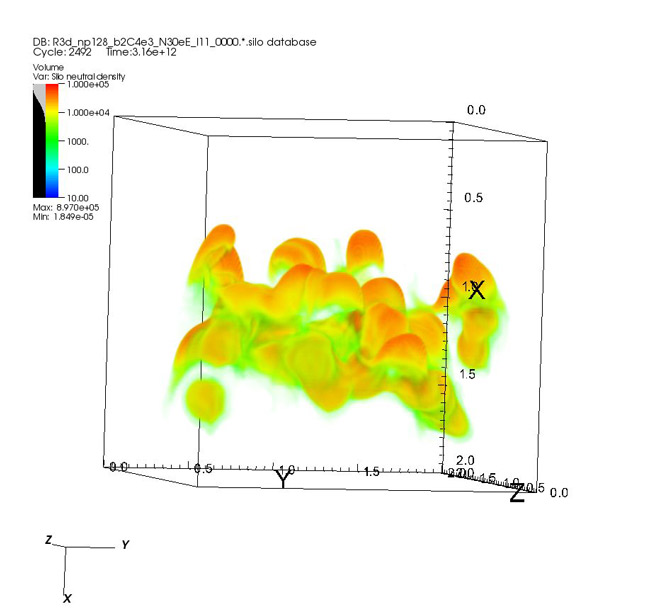

Such clumps of gas creep toward darker regions of gas anddust and createdense knots, according to new simulations. The shadows around the knots thenscreen out the intense ultraviolet radiation that might interfere with furthergas formation, the model indicates.

The research might help astronomers better understand thepillars and similar gas environments that act as stellarwombs, giving birth to new stars.

"There is, as yet, no clear consensus in theliterature regarding the formation of the pillars, except that it is mostlikely related to photo-ionization processes due to nearbymassive stars," said Andrew Lim, an astrophysics researcher at the DublinInstitute for Advanced Studies in Ireland.

Photo-ionization or photo-evaporation occurs when intenseradiation from stars energizes neutral gas clouds to create a hot outer layerof ionized gas. The hot gas then expands rapidly like an explosion and sendsshockwaves outward into any nearby clumps, Lim explained.

The process could explain how the pillars of creationpiled up in the iconicimages of the Eagle Nebula, located about 7,000 light-years away and firstspotted by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope in 1995. A light-year is the distancelight travels in a year, or roughly 6 trillion miles (10 trillion kilometers).

"We have been able to produce [virtual] pillarswhich are roughly consistent with the sizes and lifetimes which are inferredfrom observations," Lim told SPACE.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Earlier research looked only at how lone gas clumps mightlead to pillar creation. The shadow effect represents one of the prime suspectsbehind the creation process, although gas instability from the radiationbombardment might also contribute.

Perhaps the most surprising result from the newsimulations is that the largest clumps don't necessarily serve as foundationsfor the pillar-like structures, Lim noted.

But another interesting effect came from modeling a"point source" of radiation, such as a star — the photo-ionizationeffect of the radiation bombardment had a stronger influence on gaseous knobsthat could potentially grow into pillars, because of knobs having a largersurface area than just a flat surface.

"In this way the radiation field tends to 'hammerthe nail that sticks out,' making it more difficult to form a pillar," Limsaid. That again suggests the importance of the shadow effect shielding thenewborn pillars.

Lim and his colleagues used 2-D and 3-D computer modelsto test different scenarios with many different sizes and configurations of gasclumps. They next plan to study the effects of magnetic fields andgravitational effects on the pillars of creation.

In the real universe, the Eagle Nebula's pillars may havealready been knockeddown by a giant supernova explosion, according to a previous study. But thepillars will appear intact to Earth observers for another 1,000 years andperhaps permit further study, because the light we see now left the scene longago.

The current simulation results were to be presented thisweek at the European Week of Astronomy and Space Science at the University ofHertfordshire, UK.

- New Hubble Images: When Galaxies Collide

- Video - Vision of Hubble

- Vote - The Strangest Things in Space

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.