Wild Orbits: Stars Not From Around Here

PASADENA,CALIF. — A recently discovered type of cold, lightweight star follows some wildorbits around the Milky Way, a team of astronomers have found.

Someof these so-called "ultracool subdwarfs" plungealmost through the center of the Milky Way, while others venture so farbeyond the galaxy that they might be visitors from another galaxy, astronomerssaid here this week at the 214th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

Ultracoolsubdwarfs were first recognized as a unique class of stars in 2003. They aredistinguished by their low temperatures and low concentrations of elementsother than hydrogen and helium.

Theyare at the bottom end of the size range of stars, with some being so small thatthey are closer to objects called browndwarfs. They are up to 10,000 times fainter than the sun and are extremelyrare — only a few dozen ultracool subdwarfs are known today.

Thesesmall stars also move surprisingly swiftly through the galaxy.

"Mostnearby stars travel more or less in tandem with the sun tracing circular orbitsaround the center of the MilkyWay once every 250 million years," said team member Adam Burgasser ofMIT. The sun moves at about 485,000 mph (782,000kilometers per hour).

Theultracool subdwarfs, on the other hand, zip along at more than 1 million mph(1.8 million kph).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Ifthere are interstellar cops out there, these stars would surely lose theirdriver's licenses," Burgasser said.

Wildorbits

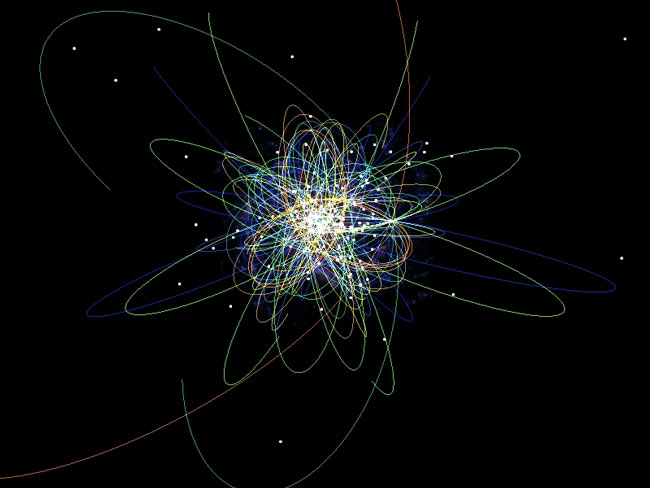

Burgasser'steam wanted to find out what kind of orbits these speedy stars followed. To doso, they assembled measurements of the positions, distances and motions ofabout two dozen of the stars and used model developed to study galacticcollisions to chart the orbits.

Theresults were surprising indeed: "These orbits were like nothing I'd everseen before," said team member Robyn Anderson, an MIT graduate student.

Someof these stars follow eccentric comet-like tracks that take them deep into thecenter of the Milky Way. Others swoop far beyond the sun's own orbit. In fact,most spend most of their time thousands of light-years above or below the diskof the Milky Way.

"Someoneliving on a planet around one of these subdwarfs would have an incrediblenighttime view of a beautiful spiral galaxy — our Milky Way — spread across thesky," Burgasser said.

Theorbital results confirm that all of the ultracool subdwarfs are part of theMilky Way's halo, a widely dispersed population that likely formed in thedistant past.

Outof this galaxy

Butone of these subdwarfs, a star dubbed 2MAS 1227-0447 in the constellationVirgo, has an orbit that is so far out that it suggests it has an extragalacticorigin.

Ourcalculations show that this subdwarf travels up to 200,000 light years awayfrom the center of the galaxy, almost 10 times farther than the sun," saidteam member John Bochanski, also of MIT. In fact, it's further even than theMilky Way's nearest galactic neighbors.

"Basedon the size of its one billion-year orbit and direction of motion, we speculatethat 2MAS 1227-0447 might have come from another, smaller galaxy that at somepoint got too close to the Milky Way and was ripped apart by gravitationalforces," Bochanski said.

Astronomershave found other stars that camefrom neighboring galaxies, but these have all been massive red giants. Thestar mapped by Burgasser's team is the first alien low-mass star.

"Ifwe can identify what stream this star is associated with, or which dwarf galaxyit came from, we could learn more about the types of stars that have built upin the Milky Way's halo over the past 10 billion years," Burgasser said.

Theteam's results were detailed in the Astrophysical Journal.

- Video ? Wild Ride Around the Galaxy

- Milky Way's Halo Loaded with Star Streams

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.