Secrets of Space Blobs Revealed

Perplexing "blobs" of gas seen in the farawayuniverse are a bit more comprehensible thanks to a new study.

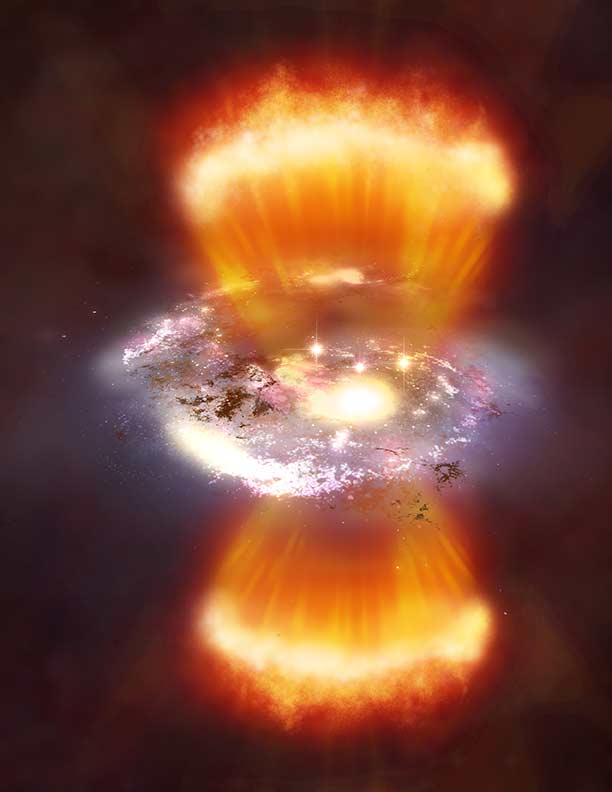

Glowing with an eerie brightness, themassive blobs seem to surround veryyoung galaxies. NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and other telescopesexamined the distant gas balls and found that their luminosity is likely due toenergy released by black holes and star formation inside the galaxies.

"For ten years the secrets of the blobs had been buriedfrom view, but now we've uncovered their power source," said James Geachof Durham University in the United Kingdom, who led the study. "Now we cansettle some important arguments about what role they played in the originalconstruction of galaxies and black holes."

Astronomers first spotted the blobs about a decade ago, butcouldn't figure out much about them, such as how they formed or why they wereglowing (hence the vague name "blob").

Recently Chandra,the Spitzer Space Telescope and other observatories pointed their lenses at apatch of space dubbed "SSA22" where 29 of these huge reservoirs ofhydrogen gas can be seen. The blobs in this field date from when the universewas only about 2 billion years old, or roughly 15 percent of its current age.

The observations revealed point-like sources of bright X-raylight - telltale signs of supermassiveblack holes ? within many of the blobs. They also showed that several ofthe baby galaxies within the gas clouds were dominated by robust starformation.

Astronomers say the radiation from the black holes and starformation could be providing the energy to light up the blobs.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It's possible that all massive galaxies go through a phasewhen they are surrounded by glowing clouds like this, Geach said. However,since that phase is relatively short-lived ? perhaps only a few hundred millionyears ? and occurs when the galaxy is very young, astronomers will have a hardtime catching most galaxies at the right moment.

"Probably all galaxies go through this phase, but tostart off with the gas is hard to detect 'cause there's nothing there to lightit up," said Sir Martin Rees, an astronomer at the University of Cambridgewho did not work on the new study. Once star formation gets going and the blackholes begin emitting strong radiation, the blobs glow for a short period oftime. "Then later the gas is either all converted into stars or blownaway," he said.

The hydrogen gas making up the blobs is likely leftovermaterial from when the galaxy formed that did not get pulled in to becomestars. In fact, the galaxies probably exist in a sea of this leftoverprimordial gas, but only a small cocoon around them is lit up and visible tous, Geach said.

"There's still a lot to learn about theseobjects," said coauthor Bret Lehmer, also at Durham. "In the futurewe'll conduct wide-area hunts for these blobs."

Geach and team will report their findings in the July 10issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

- Video: Black Hole Powers Gaseous Blob

- The Top 10 Weirdest Things in Space

- Vote: Most Amazing Galactic Images Ever

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.